(All scriptures references are taken from the New Revised Standard Version.)

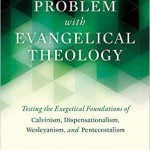

Ben Witherington III is a New Testament professor at Asbury Theological Seminary. It is an Evangelical, Wesleyan school located in Wilmore, Kentucky, near Lexington. Ben is a leading New Testament scholar and a prolific author, with many theological books to his credit.

Ben Witherington III is a New Testament professor at Asbury Theological Seminary. It is an Evangelical, Wesleyan school located in Wilmore, Kentucky, near Lexington. Ben is a leading New Testament scholar and a prolific author, with many theological books to his credit.

I know the friendly Dr. Witherington, who likes to play golf. Last November, I was rooming with my close friend Professor Scot McKnight at the Annual Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature. Scot arranged for us to have dinner with Ben Witherington one evening. I was disappointed when Ben had to cancel at the last minute since he wasn’t feeling well.

In 2005, Baylor University Press published Ben Witherington’s The Problem with Evangelical Theology: Testing the Exegetical Foundations of Calvinism, Dispensationalism, Wesleyanism, and Pentecostalism. In early 2016, Baylor Press released a “revised and expanded edition” of this book that is 333 pages in length with fine print. It is a comprehensive overview of these four strands of evangelical theology, with Witherington’s constant assessment of them.

This is an excellent book. I found myself constantly agreeing with Ben about his theological assessments. Both of us are evangelicals, though many would now deny this of me. It’s because the main theological difference I have with Ben, and most Christians, is that he is Trinitarian and I am a former Trinitarian. (See my book The Restitution of Jesus Christ at kermitzarley.com.)

The Problem with Evangelical Theology consists of five parts and fifteen chapters. The first four parts address the four, prominent evangelical theologies: Reformed, Dispensational, Wesleyan, and Pentecostal. As for me, I have a Wesleyan background and am a former Dispensationalist. And I have several relatives who are/were Wesleyan or Pentecostal.

I am surprised that Witherington, being Arminian-Wesleyan in theology, rarely mentions Jacob Arminius. But I guess that’s sort of old hat. It is especially noticeable in his chapter 2, when Ben at length says Roman 7 is about Paul’s pre-Christian life, with which I agree, rather than the common view of it that Christians have held, as did Augustine and Luther, that it is about Paul’s Christian life of struggling with sin. Arminius, in his three-volume theology, devotes his entire second volume to arguing this view of Romans 7 that Witherington adopts. In this chapter, Ben does a good and thorough job of explaining Paul’s critical use of the personal pronoun “I” (pp. 19-34). I found it interesting how Ben connects much of Reformed theology with what I agree are excesses that Augustine taught that were sharpened in his debate with Pelagius. Ben asserts, “Augustine and Luther were wrong about the bondage of the will” (p. 19).

In chapter 3, Ben Witherington interacts with Dr. James D. G. Dunn on Paul’s “works of the law” and thus what NT scholars now call “the new perspective on Paul” (coined by Dunn, pp. 45-51).

One issue in this book that is of considerable importance to me is so-called “eternal security.” Being formerly Dispensational, I was taught “once saved, always saved.” But early in my theological education, I became concerned how Dispensationalists of others often ignored the several NT texts warning professing Christians of the need to continue in faith and Christian living in order to secure eternal life for themselves. Many of these I call “the if passages” (e.g., John 8.31; Ephesians 4.21-14; Colossian 1.23; Romans 11.22; 1 Corinthians 15.2; Hebrews 2.2-3; 3.6, 14; 10.26-29; 12.25; 1 John 2.24; cf. John 3.36; 15.2, 6; Galatians 5.4; Hebrews 5.9; 1 John 2.3-4). So, these NT texts teach that a truly saved person will persevere, thus endure, in faith to the end of his/her life (e.g., Matthew 10.22; 24.13). Ben has a quotable remark about this in his saying, “One is not eternally secure until one is securely in eternity” (p. 155). While I accept this statement, I think we Christians can have a God-inspired confidence that we will persevere, which Reformed theologians often call “the perseverance of the saints.”

To me, this subject about eternal security is about getting the right balance. I still lean toward the view that a truly born again Christian will not depart from the faith and thereby lose her/his salvation. When it seems to us that a friend, relative, or acquaintance has done this, my view is that such a person was not really saved in the first place. However, I have had friends who have done this, and it is pretty hard from me to conclude that they never were Christians.

Eternal security arouses questions about election and predestination. In disagreement with Reformed Theology on the this subject, Witherington approvingly quotes C. K. Barrett, “election does not take place . . . . arbitrarily or fortuitously; it takes place always and only in Christ. They are elect who are in him . . . (cf. Gal3:29). It is failure to remember this that causes confusion over Paul’s doctrine of election and predestination” (p. 155). I like this too. I think Witherington does a terrific job in his chapter 4 of explaining Paul’s view he sets forth in Romans 9-11 about God’s election and predestination (pp. 53-80)—that it is not arbitrary as the Reformers taught.

BTW, I regard it as unconscionable for a Bible teacher to teach some theological position and then ignore critical texts that seem to oppose his/her teaching on that subject. No leading biblical scholars do this. In my opinion, those who do so are not good and just at their craft. To love your neighbor as yourself includes at least hearing his opposing view and responding to it.

In chapter 5, Ben teaches on mostly Paul’s instruction of the place of men and women in the church (pp. 81-105). Complementarianism has become a big issue in evangelical theology in recent times. I’m not sure of myself on some of these issues; so I’m quite open to learning here.

Chapter 6 is mostly about the origins of Dispensationalism (pp. 109-24). I can speak with some knowledge on this subject. Ben doesn’t always get this history correct.

First, on p. 109 Ben says Dispensationalism “apparently arose to prominence in response to a vision.” He means the vision Margaret McDonald, a member of Edward Irving’s church, supposedly had of a pre-tribulational rapture of the church. This is a double error: (1) J. N. Darby is the father of Dispensationalism, which he developed over several years, and it had nothing to do with McDonald’s vision, and (2) this old view that Margaret McDonald espoused pretribulationalism, and that it is the source of Darby’s pretribulationalism, is now regarded unanimously by historians of the Plymouth Brethren as erroneous.

Second, Ben says “Darby concluded that God had divided all of history into seven distinct Dispensations or ages” (p. 111). If my memory is correct, Darby settled on four dispensations. Such confusion is due to the fact that C. I. Scofield, in his later and very popular Scofield Reference Bible, advocates seven dispensations. (I wore out an Old and New Scofield.) Yet Ben is fair in stateing, “To their credit, Dispensationalists recognized rightly that the NT has a profoundly eschatological orientation and much to say about the future, and indeed even a good deal of OT prophecy seems to have not yet been fulfilled” (p. 112).

Third, Ben says Darby “was to become the founder of the Plymouth Brethren” (p. 110). On the contrary, this movement was started in Plymouth by thee men in 1827-28, and I think two were Croats and Croix. B. W. Newton was then a Plymouth resident matriculating at Oxford. When home, he attended these private meetings that centered on “the Lord’s supper.” Newton then invited another Oxford student and friend, J. N. Darby, to attend these meetings. Darby’s home was Dublin, Ireland, where a similar meeting soon emerged. Since the “assembly” at Plymouth was larger and more prominent, the eventual movement took the name Plymouth Brethren. Newton and Darby then became the two most prominent Bible teachers of this movement until 1945, when there was a split. Darby then became the founder of the Exclusive Brethren, so that it is quite incorrect to call him the founder of the Plymouth Brethren.

Witherington concludes this chapter 6 with some of his interpretations of the endtimes. He says, “There will be no final great battle between human forces called Armageddon, . . . This makes all speculation about some great Middle Eastern war between human combatants not only otiose, but odious, since in fact the NT suggests a different end-game scenario involving direct divine intervention” (p. 123). Wow! I strongly disagree with that? See my book, Warrior from Heaven (2009). Wesleyans are not known for their eschatology. Nevertheless, I really like Witherington’s book, Jesus, Paul and the End of the World, and I plan to review it as well.

The NT confirms the strong OT prediction that the Messiah literally will come at the end of days to deliver Israel from complete annihilation. That is why Jews never accepted Jesus as their Messiah. Their failure was in not realizing that the messianic motif could be compatible with others in the OT, such as Isaiah’s suffering servant (Isaiah 42-55), both of which Jesus will fulfill due to two comings.

Let’s first examine the OT. Isaiah indicates that Messiah will be a warrior king who will deliver Israel from its enemies by saying of the “branch,” whom Jews always have rightly identified as the Messiah, that he “shall strike the earth with the rod of his mouth and with the breath of his lips he shall kill the wicked” one (Isaiah 11.14), who is the Antichrist. The Apostle Paul confirms this in 2 Thessalonians 2.8. And King David writes, “Why do the nations conspire, and the peoples plot in vain?” (Psalm 2.1). What do they plot? “The kings of the earth set themselves, and the rulers take counsel together, against the LORD [God the Father], and his anointed [=Messiah], saying, ‘Let us burst their bonds asunder, and cast their cords from us’” (v. 3). Then David says the LORD laughs at them and declares, “I have set my king on Zion, my holy hill” (v. 6), referring to Jesus’ second coming. Zechariah the Prophet describes this endtimes scene in which all the militaries of the world’s nations will gather into the land of Israel to annihilate the tiny nation of Israel (Zechariah 12.1-9). He adds, “Then the LORD will go forth and fight against those nations . . . On that day his feet shall stand on the Mount of Olives” (Zechariah 14.4), referring to his agent “my shepherd,” who is Jesus (Zechariah 13.7-9; cf. John 15; Acts 1.11).

But David’s even more vivid psalm, the most quoted in the NT and applied to Jesus, that presents this same endtimes scenario is Psalm 110.1-3. It reads, “The LORD [God the Father] says to my lord [Jesus], ‘Sit at my right hand,’” referring to Jesus heavenly ascension. Then David adds, “until I make your enemies your footstool. The LORD sends out from Zion your mighty scepter. Rule in the midst of your foes. Your people [surviving Israeli Jewish men] will offer themselves willingly on the day you lead your forces on the holy mountains. . . . The LORD is at your right hand; he will shatter kings on the day of his wrath.” Zechariah says the LORD [YHWH=God the Father] will do so by empowering King Messiah Jesus and those volunteer Jews (Zechariah 10.3-6; 12.3-9). So, it is both God and surviving, Israeli, Jewish men led by Jesus who will fight against these nations’ militaries and soundly defeat them (14.3-14).

Or let’s take the NT, as Ben offers. He obviously, and I think wrongly, must interpret Revelation 19.11-16 non-literally. It says Jesus, as “King of kings and Lord and lords,” will depart heaven and return to earth as a mighty warrior, leading “the armies of heaven,” God’s angelic “host,” in doing tremendous battle at the endtimes. It is not called “the battle of Armageddon,” which is a misnomer, but the “battle on the great day of God the Almighty” (Revelation 16.14-16). Those hostile kings of the nations will merely meet at Harmegedon to plan strategy for annihilating Israel, and the center of this conflict will be Jerusalem and its Mount Zion.

In chapter 7, Ben addresses the Dispensationalists’ key doctrine in their eschatological scheme—the pretribulational rapture of the church to heaven seven years prior to Jesus returning to earth to establish his millennial kingdom. I disagree with Ben that those “taken” in Matthew 24.40 are taken in judgment (p. 126). Even Dispensationalists disagree about this, though most say, as I believe, that they are the saints whereas Hal Lindsey agrees with Ben. But I agree wholeheartedly with Ben that Jesus and the apostles did not teach that the parousia (Gr. word for “presence,” used to refer to Jesus’ second coming) was imminent. And Ben and I disagree with Dispensationalists saying the pretrib rapture is imminent.

As a former Dispensationalist, I believed in their teaching that what they call “the rapture of the church” has always been imminent, meaning it could occur at any time. But I changed in 1971 and have thereafter been a historic posttribulationalist, which I think Ben is, meaning that Jesus will only come back one time, and this at “the end of days,” thus at the end of the tribulation.

I am surprised at the novel interpretation (which I had never heard or read) that Ben takes of the important eschatological text Dan 7.13-14. Without identifying “one like a son of man,” Ben says he “comes with the clouds to meet the Almighty on earth for the day of judgment” (p. 131). On the contrary, Jesus constantly called himself “the Son of Man” and thereby identified himself as that figure in Dan 7.13-14. Plus, this text is the main biblical source for his kingdom teaching. And Jesus further alluded to this shortly before his arrest by telling a parable about himself by saying, “A nobleman went to a distant country to get royal power for himself and then return” (Luke 19.12).

Although Ben and I agree about posttribulationalism, to me he appears to err by saying, “1 Thessalonians 4:14-30 is not about the rapture” (p. 132). Ben later concludes, “If there is no rapture, much of the Dispensational system falls down like a house of cards” (p. 143). We need to be clear here, that “rapture” refers to the taking up, not to pretribulationalism. This text does not say when these saints will be taken up in relation to the final tribulation. I think a comparison of it with Jesus’ Olivet Discourse shows that this taking up, which I accept as calling it “rapture,” is posttribulational. And I don’t think Ben and so many commentators are right in saying the saints, here, go up to escort Jesus to earth as was an ancient custom for kings returning as war victors to their people (p. 133).

I commend Ben for concluding, “Here is where I say that we must be thankful to Dispensationalists for putting eschatology and especially the return of Christ back on the front burner in the last century and a half, and for arguing long, and correctly, that Revelation 20 is after all about a millennial reign of Christ on earth The early church prior to Augustine knew this” (p. 144).

Sometimes in Witherington’s book he states his belief in Classical Incarnation with which I also strongly disagree. On pp. 152-53, he mentions such critical texts to this subject as Romans 9.5, Philippians 2.5-11, and Romans 10.9 compared with Joel 3.5, and then asserts, “Paul has christologically redefined how he understands monotheism” (p. 153). Ben thus adopts the same view that Larry Hurtado and Richard Bauckham are so well known for advocating, that Paul splits the Shema in 1 Corinthians 8.4-6 and Ephesians 4.4-6. I regard this as impossible because, if true, Paul would have encountered so much opposition for such a view from both Jews and Jewish Christians that it could not have escaped mention in Acts or Paul’s NT letters. And it would have been a colossal change from his previous monotheistic stance as a Pharisee that he would not have avoided mentioning this. So, I think this interpretation of the NT data–that Jesus is both man and God–is eisegetical, not exegetical. But this is a complicated subject since many of the critical NT texts on this subject must be considered in their original Greek.

In chapters 9-11, Ben critiques John Wesley’s synthetic theology, and I think he is fair in doing so. He says due to Wesley’s positive thinking, he wrongly adopted a form of postmillennialism (p. 188), which was indeed popular in his time. Ben explains, “Wesley never did emphasize future eschatology to the degree the NT does, and this is a weakness in Wesleyan theology then and now, for which Dispensationalism more than overcompensates” (p. 197). I agree with Ben that Wesley’s great contribution is his spirit of evangelism, love, and exhortation to overcome sin in Christian living, but that he merely went too far with “entire sanctification” (pp. 213-21).

In Ben’s brief treatment of Pentecostalism (pp. 225-37), he makes an interesting statement about the newly-risen Jesus saying to his disciples on the first Easter evening as he breathed upon them, “Receive the Holy Spirit” (John 20.22). Ben says, there is no evidence whatsoever that the Spirit was actually received in the upper room at Easter. The proper way to read that story is that Jesus is performing a prophetic sign act, promising and reassuring that the Paraclete will come when he [Jesus] goes back to heaven” (p. 227).

Witherington thinks Pentecostal Gordon Fee (one of Ben’s teachers) is right in saying tongues today “is a gift for private prayer,” and Fee “is absolutely correct that I Corinthians 13:1 suggests glossolalia is an angelic language” (p. 235).

Some other points Ben makes in this book with which I agree:

- The Wesleyan-Holiness Movement went too far with its “entire sanctification” (pp. 215-21).

- Pentecostals err with their doctrine of subsequence regarding Spirit baptism (pp. 226-34).

- Dispensationalists err in asserting there are two peoples of God—Israel and church (p. 5).

- Cessationists err in denying many spiritual gifts as in the NT, such as tongues (pp. 234-37).

- “Water” in John 3.5 refers to a woman’s water issuing, signifying birth is near (pp. 200, 212).

I love an attitude Ben espouses, that Bible students should have “a generosity of spirit, and willingness to listen and learn that you might be wrong in your interpretation of the NT. . . . Theologizing should be a collegial, community activity, not shots fired in anger or anxiety from our private citadels” (pp. 266-67).

Despite some disagreements I have with this book, which all book reviewers usually have in reviewing books, I highly recommend this book for students of evangelical theology and Bible.