Adam Hamilton is the senior pastor of the United Methodist Church of the Resurrection in Leawood, Kansas, “one of the fastest growing, most highly visible churches in the country” (see here). He is the author of several popular books, and in his book When Christians Get it Wrong, he writes that the Bible is a document that is both divine and human, which for him means that the authors “were people who had a deep faith in God” who “heard and understood God in light of their culture and times.” He goes on to write that “..the Bible is the timeless, inspired word of God found within the writings and reflections of very human authors.” (italics mine, quote from here)

From a more scholarly perspective, Stephen Fowl, in his book “Engaging Scripture”, writes the following

“…theological convictions, ecclesial practices, and communal and social concerns should shape and be shaped by biblical interpretation” and “Biblical interpretation will be the occasion of a complex interaction between the biblical text and the varieties of theological, moral, material, political, and ecclesial concerns that are part of the contexts in which they find themselves.” (p. 60).

How do these views of the Bible compare with those of the 16th century church Reformer Martin Luther? Not long ago I had noted that at a recent theology conference in Bloomington, Minnesota, my pastor, Paul Strawn, had given “a rip-roaring scholarly paper” titled “Martin Luther’s Sola Scriptura”. The paper has not been published yet, but I have been given permission to publish some excerpts from the paper, which are found below.

In the paper’s introduction, Strawn writes about the recent history of the phrase “sola Scriptura” in his church body, the Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod:

“The Latin expression sola Scriptura (by Scripture alone) used to be regularly included in the slogan that summarized the Reformation of the western church in the 16th century via Martin Luther (1483-1546): sola scriptura, sola gratia, sola fide. At the last centenary of the Reformation in 1917 it was accepted as an accurate summation of the causes of that event.[1] It was incorporated into the newly designed seal of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod in 1948 and popularized by the Oscar-nominated film Martin Luther in 1953—a film on which both Theodore G. Tappert (1904-1973) and Jaroslav Pelikan (1923-2006) served as consultants. A more recent (apparently) derivation of the slogan replaces sola Scriptura with solus Christus, that is, instead of Luther’s championing of the Bible being a leading cause of the Reformation, it was his confession of Christ…..

He goes on to provocatively state:

So perhaps can be understood the liturgical innovation of late of removing the place where the lectionary—a book containing the readings from the Bible used in worship—has traditionally been placed and from which it was read: the lectern… The Bible no longer has an authority in its own right deserving its own liturgical appointment (lectern) as does baptism (font) the Lord’s Supper (altar) and preaching (pulpit). Instead, its authority is derived from its proclamation (from the pulpit) by the church (the pastor).

The paper’s first section is titled “Scriptura Plastica”. Some of the highlights from this section:

- The idea of establishing an original text of the New Testament (i.e. an “autograph”) was abandoned already in 1979, by critical scholar Kurt Aland, in the 26th edition of the Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece (the critical edition of the Greek New Testament). A new process, called the “local-genealogical method”, or “eclecticism” was adopted instead.

- The contemporary “coherence-based genealogical method” is the newest method whereby scholars endeavor not to discover the original text of the New Testament, but rather the first “witness” in the New Testament tradition.

- According to Strawn, we now have “witness criticism”: “The use of this term ‘witness’ is not insignificant, for it was an important term in the theology of the preeminent Protestant (Reformed) theologian of the 20th century, Karl Barth (1886-1968), allowing him to assert that in Scripture, you don’t necessarily have the Word of God itself, but the fallible ‘witness’ of man to God’s Word.”

- “…the methodology of NA28 [i.e. the 28th edition of the Nestle-Aland text noted above] has further implications, specifically that of the authority of Scripture, or in essence, the meaning of sola Scriptura”, and this has prompted some to suggest that traditional approaches towards biblical hermeneutics (that is the art and science of biblical interpretation) need to be reconsidered.

The final point made in this section:

- “Why did [Martin] Luther take a number of manuscripts, reduce them to a single text, insist that that text was the inerrant Word of God, and also that its simple meaning be pursued? Was is that Luther was simply ignorant? Or could it be that he had a difference understanding of sola Scriptura than what we have today?”

The next section of the paper is titled “Luther and Scripture”. Within this section, the following points are made:

- Martin Luther lived during a time when the Bible was seen to exist as a fixed text (i.e. Jerome’s Latin Vulgate), and he personally had extensive exposure to the Bible in this form while growing up.

- “The sheer volume of Luther’s interaction with the Bible simply overwhelms. He read the Bible cover to cover twice a year.. Luther prepared a timeline of the history of the world, based on the text of Scripture… he translated the entire Bible from Hebrew and Greek into German (1534).” Throughout his life he held classes on many of the particular books of the Bible.

- It is interesting to note that Luther received his first degree in Aristotelian philosophy and even taught the same. That said, in the long run, he “bypassed Aristotle (philosophy), Plato (mysticism), Lombard (medieval theology) and the patristics (Dogmengeschichte) and spent his life studying, teaching, preaching and translating the Bible.”

- According to Luther, “The reason Scripture has never erred, is ‘clearer, simpler, and more reliable,’ and ‘alone is the true lord and master of all writings and doctrine on earth.’ The Bible is the ‘book of the Holy Spirit’ Luther asserted in comments on Psalm 40:8-9.[2] The Scriptures ‘did not grow on earth’[3] but ‘have been spoken by the Holy Spirit.’”[4]

- “Thus Scripture, for Luther, seems ultimately to be a matter of the work of the Holy Spirit, especially in view of the end times, who is to convict the world of ‘Sin, righteousness and judgment’” (John 16:8).[5]

The final section of the paper is titled “Luther and the Texts of Scripture”. There, we read:

- “Even though Luther grew up hearing and studying the text of Jerome’s Vulgate, he was not unaware of its textual tradition. Jerome’s edition was not a straight translation… already in 1504, when Luther was 21, the first edition of the Vulgate with variant readings had been printed.”

- In Erasmus’ “Textus Receptus”, “he also compared the Byzantine texts [Greek texts of the New Testament] to the references to Scripture found in the writings of the church fathers[i]—something not done with the critical text until the middle of the 20th century!”

- “Erasmus apparently had access to the Greek manuscripts of the Eastern fathers he mentioned. This is not insignificant, for it means that he had access to some of the earliest manuscripts of Scripture known today.” (see a summary of another important paper by my pastor here: “An Overview of the Influence of the Publication of Patristic Literature Upon the Reformation”)

- Why did Luther undertake the translation of Scriptures into German at all? “Eighteen editions of the Bible in German—fourteen in High German and four in Low—were published before Luther’s… the reason was clarity of meaning: a Bible which people could read and understand.”

- For Luther, “the literal or historical meaning of the text was its Christological meaning, since the center of Scripture was Christ…” As he said: “In the Scriptures, therefore, no allegory, tropology, or analogy is valid, unless the same truth is expressly stated historically elsewhere. Otherwise Scripture would become a mockery.”

- “How did all of these resources which clearly revealed a complex history of the textual transmission of Scripture affect Luther? It really seems not to have been an issue at all. A text, a clear text is assumed, and consequently, bad renderings, bad translations, can be spotted and corrected.”

- “Modern scholarship…most assiduously endeavors to create unique contexts for each author, language and time period. Luther had no such proclivity, believing apparently Scripture to be a coherent whole, in spite of its many writers, languages, historical contexts and transmission issues.”

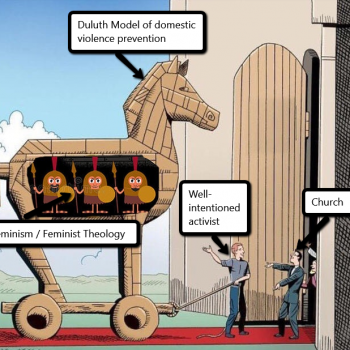

The views of Hamilton and Fowl, noted at the beginning of this article, are both related to the teachings of Karl Barth, i.e. his “Neo-Orthodoxy”. Approaches like theses are decidedly different from those of Luther. In the paper’s conclusion (you can read the entire conclusion, as well as other quotes from the paper in this article, which examines these issues in a larger context), we read the following: “The Bible as we have it is a work of the Holy Spirit even in these end times. Therefore, in spite of the questions raised by modern textual criticism, it remains without error, readable and understandable.”

Some in the church today would see this as opposed to solus Christus. This would have made absolutely no sense to Martin Luther. As noted earlier in the paper, the Church has always viewed the Scriptures as “a third-article topic, as that of the work of the Holy Spirit in history” and not “so much as of that of the second article, the person of Christ, in the present.”

FIN

Note: if you would like to talk to my pastor about his paper, he can be reached at [email protected]

Notes:

[1] Theo. Engelder, “The Three Principles of the Reformation: Sola Scriptura, Sola Gratia, Sola Fides,” in Four Hundred Years. Commemorative Essays on the Reformation of Dr. Martin Luther and Its Blessed Results. In the Year of the Four-Hundredth Anniversary of the Reformation. By Various Lutheran Writers, Ed. by W.H.T. Dau (St. Louis: Concordia, 1916), p. 97-109.

[2] Walch 2nd ed., IX, col. 1775.

[3] Sermon on John 3:34 (ca. 1538-1540), Walch 2nd ed., VII, col. 2095.

[4] From the Last Words of David (2 Sam. 23: 1-7), Walch 2nd ed., III, col. 1895.

[5] Cf. Martin Luther, Convicted by the Spirit, trans. by Holger Sonntag (Minneapolis: Lutheran Press, 2009).

[i] “Complete New Instrument diligently reviewed and improved by Erasmus of Rotterdam in relation to not only the Greek truth but also the trustworthiness of many codices – old and improved – of both languages [Greek and Latin]; then also in relation to the quotations, improvements, and interpretations by the best authors, chiefly Origen, Chrysostom, Cyril, Vulgarius [d. 928], Jerome, Cyprian, Ambrose, Hilary [of Poitiers d. 367] , Augustine – together with annotations that may instruct the reader concerning what has been changed for which reason. Therefore, whoever you are and love true theology, read, understand, and then judge. And do not be offended right away, should you indeed find fault with what was changed, but consider whether it was changed for the better.” (NOVVM IN strumentū omne, diligenter ab ERASMO ROTERODAMO recognitum & emendatum, nō solum ad graecam veritatem, verumetiam ad multorum utrius [que] linguae codicum, eorum[que] veterum simul & emendatorum fidem, postremo ad probatissimorum autorum citationem, emendationem & interpretationem praecipue, Origenis, Chrysostomi, Cyrilli, Vulgarii, Hieronymi, Cypriani, Ambrosii, Hilarii, Augustini, una cū Annotationibus, quae lectorem doceant, quid qua ratione mutatum sit. Quisquis igitur amas veram Theologiam, lege, cognosce, ac deinde iudica. Ne[que] statim offendere, si quid mutatum offenderis, sed expende, num in melius mutatum sit) (Basil: Froben, 1516).