A big thanks to everyone who’s responded this week to my request for $20 donations toward raising $10K for Project TURN, School for Conversion’s prison-based education program. We’ve not yet reached our goal, but we’re off to a good start. And we have a few weeks left til the end of August. We have learned that God is faithful, but rarely early. “Give us this day our bread for today.”

I’ve been on vacation with my family this week, but wanted to share this beautiful piece, which is also a word from behind bars. Thanks to Chris Hoke, a great writer who’s been learning the Jesus Way as a jail chaplain, a gang pastor, a book nerd, a small underground coffee roasting business member, and a singer of songs in Skagit Valley, Washington. He shares about what he’s been learning from Neaners, his friend in solitary confinement.

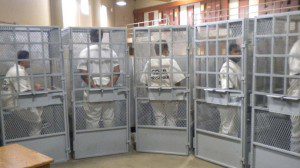

My friend Neaners called me collect from a Washington State prison yesterday. His voice echoed from where he stood handcuffed in a small hallway. He told me he was back in the “hole”—solitary confinement.

“So I’m back in the hole,” he said with an almost chipper voice.

“What? No . . . What happened?”

Neaners, born José Israel Garcia, now thirty, spent much of his young adult life as the leader of a Mexican gang in the misty agricultural fields of the Northwest. I met him seven years ago in a jail Bible study when I was a new volunteer chaplain there. Our friendship has grown over these years. He ushered me into my vocation as a “gang pastor,” and over time he has been won over to the beauty of Jesus and His mission. Neaners sees in Jesus the kind of “gang leader” he’s always wanted, and wanted to be: one who risks his neck with the authorities to love, gather, and empower the outcasts. Neaners has also discovered how God sees him: in a letter from solitary confinement last year, he wrote, “It’s just so f—king beautiful, to know I’m God’s babyboy.”

God’s adoption of Neaners as a son had implications for others. Like me. I felt called to stick with Neaners as if he were my own brother, bound by something even thicker than blood. So we have made plans for his release in 2014. He is planning on living in our ministry community at Tierra Nueva and working together with me and others to reach more gang youth. But until then, it has meant that each setback he experiences in prison affects me and others pulling for him. He just got out of solitary confinement a few months ago. Then he got pulled into a fight, maced in the face, and lost hope back in the hole. Then he was released. Now this call.

“I guess one of the homies in here took off on a cop,” he said, “and a fight popped off.” He told me how officers immediately came to his cell. They assumed he was behind the fight, orchaestrating it, since he is one of the older and most tattooed inmates in that sector of the prison. They told him the investigators wanted to talk. Neaners answered honestly: he knew nothing about the incident. “So they said OK, Garcia, turn around and cuff up, and took me to the hole.” He had to keep a straight face, swallow, and say goodbye to his new celly, his pictures we send him, and all the books on trauma, healing, art and the Bible he has accrued.

“I’m not trippin’,” he assured me. “I kinda miss the hole. I can really read and pray in there with no distractions. Plus, I’ve been slacking on getting back to so many people who have written me.”

This is rare; the use of prolonged isolation has been under fire from human rights organizations for years due to the psychological damage experienced by inmates left in solitary. All the people writing to him over the last year or more has helped turn his cell of lonesome torment into a womb of transformation. Christians across the country who have been reading an email series I send out with portions of his letters from last year, Notes from Solitary Confinement, have been praying for him and corresponding with him, penitentiary envelopes in their mailboxes and all. I believe these kinds of connections have not only woven him into the larger Body, but have helped mystically put him in contact with our Father, who is nearer to him in there than any of us can be.

Neaners didn’t call to talk about himself, though. He wanted to tell me about this other inmate, why he had assaulted a prison officer. “This was a real wake up call for me, babyboy.” Now he calls me babyboy.

“I didn’t even know this guy,” he began, “but I just found this out: he only had sixty days left ‘till his release. And he had no one. No family, no release address, no one. Just the streets.”

So by attacking an officer, this other desperate inmate was assured an extended stay in prison.

“He had no hope, homie,” Neaners said through the line. “See, in here, if you need a soap, some socks, some coffee, whatever, we got your back. We share and take care of each other. We say goodnight. But out there, this fool had no one to even say goodnight to him. No one wanted him.”

So Neaners and ten others are back in the hole as I write this, and an officer was attacked, all because another homie had no hope. No one to bring him home.

“That’s when it hit me hard: this is what God’s call, what our mission, Hope for Homies, is all about.” Hope for Homies is the name Neaners has given to his vision for gang ministry, including a farm and a home for so many gang members he knows who really have nowhere they are safe, where they belong and cherished. He wants work with Tierra Nueva and other churches and businesses when he gets out to do for many other tattooed felons what has been done for him.

“Tell people, Chris,” he said as rushed to wrap up in the last 30 seconds, “Tell people about this guy. That’d be me if it wasn’t for all of you. I want people, Christians, la familia, to understand this vato’s hopelessness.”