In this month’s Conversations Under the Oaks, I had two questions on language and languages that I want to address together.

How far does the study of language and archaeology work into your worship and relationships with the Gods?

and

Some cultures pray aloud; the West prays silently, assuming (perhaps) that Gods read minds. Is there any lore to back this up? What of those who learn a foreign (or extinct) language just to communicate with their chosen Gods?

I’ll start with the easy part. I don’t really agree that the West prays silently, considering the long tradition of spoken prayer in both the Catholic and Protestant traditions. Still, virtually all Christians agree that their God hears silent prayers. Further, I think there’s a difference between reading minds and hearing thoughts.

I have lots of thoughts on language in regards to our experiences of the Gods and our conceptions of Them. Those thoughts begin in the beginning.

The Gods are older than language

How old are the Gods? We tend to associate the first appearance of deities with the records of the people who first worshipped Them, but at least some of the Gods are older than that. Far older.

Are the various Sun Gods 4.6 billion years old? Are the many Moon Goddesses 4.5 billion years old? What Gods were on or around the Earth in the age of the dinosaurs? We can’t answer these questions with any precision, but it would be the height of human arrogance to assume the Gods did not appear until we did.

We do not know when humans developed the capacity for language. The other existing species of hominids do not have it, so it is virtually certain that our earliest human ancestors didn’t either. Did one of our intermediate ancestors have it and pass it down to us? Or is language the evolutionary mutation that gave homo sapiens sapiens the ability to begin spreading around the globe around 70,000 years ago?

To be clear: individual languages are human inventions. But the capacity for language is a biological feature, a product of evolutionary processes.

The Gods are older than language. We have evidence (primarily burials with grave goods) of religious behavior by human species who did not have language. We cannot know what Gods spoke to these ancestors or what relationships they formed, but it is entirely reasonable to conclude that humans do not need language to encounter the Gods.

The Gods transcend language

Many mystical experiences are described as ineffable. We can’t talk about them, not because it’s forbidden, but because words cannot adequately describe them. I suspect these experiences are virtually identical to the experiences our earliest ancestors had of Gods and spirits.

We contemplate these experiences using language – as best we can – because that’s what we do. But the core of what They have to say to us is not words, even if we “hear” it in words. Rather, it’s ideas, concepts, and images.

So, it is not necessary to learn a specific language or any language at all to communicate with the Gods. You do not need to learn Greek (either ancient or modern) in order to worship Zeus, pray to Zeus, or to hear Zeus, should He choose to speak to you.

However, religion is more than experiences of the Gods and relationships with Them. Religion is also about practices, culture, and community. And one of the core elements of a community is a shared language. If you want to be part of an extant community, you need to be able to speak and read their language.

The problems with translation

Even if your religious community is here in the United States and your shared language is American English, there is still value in learning the language of your hearth culture. Most Pagans rightly value the writings of our ancestors, and none of them were written in modern English. We rely on translations done by others who almost never share our religious outlook.

There is no such thing as a “neutral” translation. Different languages aren’t just a collection of different words. They have different grammar structures, different idioms, and different taxonomies. How many times do you say “what do you mean by that?” to someone who’s speaking your native language? Now try doing it with a different language.

Every translation has a perspective and every translation reflects a series of choices made by the translator. There are over 450 translations of the Bible in English alone – all of them reflect the choices of their translators. Meanwhile, Muslims say that if you haven’t read the Quran in Arabic, you haven’t really read the Quran.

I recently had the opportunity to preview Morgan Daimler’s upcoming book Raven Goddess: Going Deeper with the Morrigan (scheduled for publication October 2020). It’s primarily intended for beginning and early intermediate devotees of the Morrigan. But it has value for those of us who are more experienced, because it includes Daimler’s translation of key texts related to the Great Queen. I believe this is the first time some of these texts have been available in English and translated by someone who sees the Morrigan as an actual deity – and who doesn’t censor the text because of sexual elements. That perspective matters.

My personal practice

As for my practice, I’m monolingual. My only regret from all my years of schooling is that I never learned another language. Don’t send me links to Duolingo – at this age I have other priorities. I’m aware of the intricacies of language and the problems with translations and I count on that awareness to keep me from jumping to inaccurate conclusions about what words really mean.

I do my best to pronounce non-English names and key words properly, but I don’t obsess over it. And I have no patience with those who insist their preferred pronunciation is the only proper one – especially those who aren’t native speakers. Irish, Welsh, and Scots Gaelic all have ancient and modern variants as well as regional dialects – just like English. Modern Greek is not the Greek of Homer or Plato.

That said, not every pronunciation is a good pronunciation. Samhain was never, is never, and never will be pronounced SAM-hane.

But be kind to those who say it that way out of ignorance – you were a beginner too at one point.

A religion for who you are, where you are, when you are

The first question mentioned archaeology. As with language, I’m informed and inspired by what archaeology, anthropology, and history can tell us about our ancestors and their beliefs and practices. But at the end of the day I’m not a pre-Roman Celt or a Pharaonic Egyptian, nor am I a contemporary Greek. I’m a 21st century American whose only working language is English. My Paganism and polytheism are a religion for here and now.

If you want to be a part of a culture that speaks a different language, learn it. If you want to read source material for yourself, learn the language.

But you don’t need a different language – or any language – to speak with the Gods.

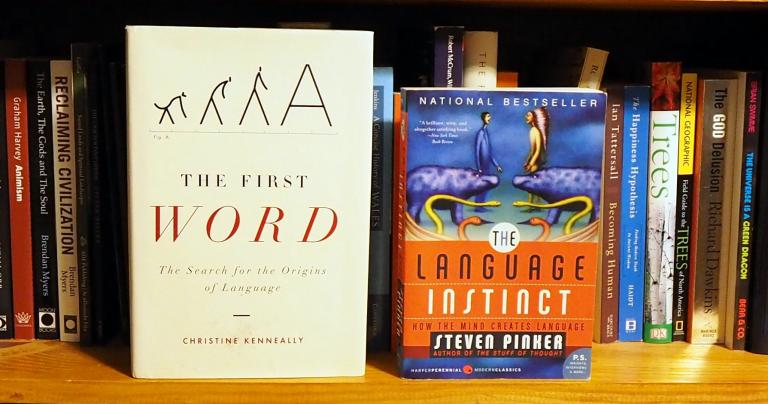

For more on the roots and nature of language, I recommend The Language Instinct by Steven Pinker and The First Word by Christine Kenneally. The Language Instinct takes a psychological approach and looks at how language develops here and now, while The First Word takes an archaeological approach and provides informed speculation on how language first originated. Either would be a good addition to your library – both would be better.