The Patheos “What Do I Really Believe” series has a new question for contemplation across religious traditions.

The Patheos “What Do I Really Believe” series has a new question for contemplation across religious traditions.

Most religious traditions teach that human beings have agency – that their choices matter – but also that there are greater spiritual forces at work that impact or even determine the course of events or the ultimate outcome. To what extent does divine will (or fate or karma etc.) limit human agency? Does free will really exist?

My initial response is “of course it does!” Pagans like to speak of “true will” and of “working our will.” For Wiccans and their spiritual relatives, interfering with the free will of another is one of the most serious sins. And there’s the powerful line in S.J. Tucker’s song “Witchka” – “a witch decides a witch’s fate.”

But move out of the realm of the magical traditions and things get a little murkier. The Greeks have the three Fates, who spin, weave, and cut the threads of our lives. The Norse Norns have a similar function, and while I’ll leave an explanation of wyrd to a Heathen who has a first-hand understanding of it, it clearly has at least an element of destiny to it.

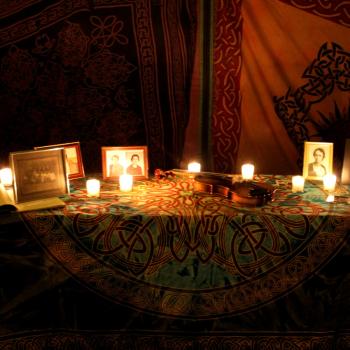

The Celts have an element of this too. After I posted the pictures from our Beltane circle where we told the story of Cú Chulainn and his dealings with Morrigan, a very knowledgeable Pagan told me we had it wrong. Cú Chulainn, he said, did not die because he refused the aid of Morrigan. He was going to die all along, and like a good Celtic hero he tried to live valiantly in the face of his fate. I argued that while that may have been the original meaning of the story, it’s not the meaning we should take from it here and now.

The Celts have an element of this too. After I posted the pictures from our Beltane circle where we told the story of Cú Chulainn and his dealings with Morrigan, a very knowledgeable Pagan told me we had it wrong. Cú Chulainn, he said, did not die because he refused the aid of Morrigan. He was going to die all along, and like a good Celtic hero he tried to live valiantly in the face of his fate. I argued that while that may have been the original meaning of the story, it’s not the meaning we should take from it here and now.

People draw general conclusions about the nature of the world from their specific experiences. If you have a lot of control over your life, you tend to believe in free will and in the efficacy of your own actions. If you don’t have much control, you tend to believe everything is controlled by fate or God or brain chemistry or the Bilderbergers.

No matter which view is correct (in whole or in part) what’s indisputably true is this: taking action to improve your life is more likely to result in improvements than not taking action. Whether you believe you’re taking action because of your own will or because it’s your fate isn’t nearly as important as the fact that you’re doing something.

Whether we have free will or not, we are far better off ordering our lives as though we do.

But that doesn’t completely answer the question of whether or not free will exists.

Einstein said “God does not play dice.” Stephen Hawking responded “not only does God play dice, sometimes he throws them where they can’t be seen.” The Universe in which we live is probabilistic, not deterministic – it’s dice, not the clockwork imagined by the Renaissance astronomers and philosophers. In a probabilistic universe, anything is possible. But some things are so likely they’re practically certain, while other things are so unlikely they’re practically impossible.

The actions that flow from your will don’t guarantee results, but they move the odds in your favor. Align your actions toward consistent goals over a long period of time and the odds improve to the point where they become highly likely.

The power of consistent application of will is strong, but that power is impacted by two very important factors. The first is the fate you build for yourself.

Whenever you make a choice, you say “yes” to one thing and “no” to everything else. But you don’t just say no to the choices you rejected, you also say no to everything that would have followed those choices. Shortly after I graduated college, I was dissatisfied with my job. I looked into going to graduate school full time. But I already had a car payment – quitting my job would mean losing my car. The decision to buy a car – that seemed so simple and necessary at the time – had effectively eliminated the option of going to graduate school full time. With the loss of that option I also lost all the experiences I would have had as a full time graduate student and I locked myself into a series of experiences (and future options) in full time employment.

Make enough choices – including choosing not to choose and including choices you don’t recognize as choices at the time – and eventually you find yourself on a path that bears a strong resemblance to fate, even though it is simply the cumulative consequences of your free will.

The second important factor impacting your free will are the currents of power and will running throughout the Universe. We can debate the wisdom and ethics of various governments and their laws, but they clearly have the power to restrict your free will. When your will collides with the will of others, something has to give – it may be you. And when your will runs counter to the currents of the Universe – when you hike in the desert without carrying enough water, when you stand in the path of an angry boar, or when you build a beachfront home in a hurricane zone – you’re almost certain to come out on the short end. Are the results “fate”? Or are they simply what happens when humans are ignorant and arrogant?

And what of the gods? The Calvinist argument that free will cannot exist because it would limit the sovereignty of Yahweh is meaningless to Pagans (and pretty much everyone else, with the interesting exception of Muslims – inshallah). The gods are actors in the Universe the same as us, only stronger and wiser. The stories of our ancestors as well as the experiences of some modern Pagans show that the will of the gods does not eliminate our will. But when those two wills come into conflict, well, see the examples in the previous paragraph.

The question of free will versus fate is a philosophical question that cannot be answered with complete certainty. But the overwhelming evidence shows we are better off assuming we do have free will and conducting our lives accordingly.