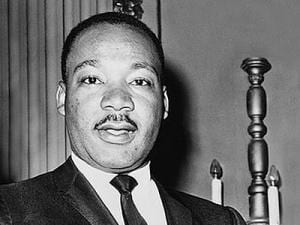

In December 1964, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther Ling, Jr. was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. In his laureate lecture, Dr. King spoke of a “world house,” calling on his listeners to embrace a vision of humankind as interconnected and interdependent. The great Civil Rights leader argued that people had become “unduly separated in ideas, culture and interest,” and that because “we can never again live apart, [we] must learn somehow to live with each other in peace.”

Dr. King’s words are just as resonant (or more so) today as when he first uttered them over fifty years ago. Advances in high-speed travel and digital communication provide us with unprecedented opportunities to interact with people from different walks of life. In order to foster a healthy democratic society and enrich our communities, we need spiritual and ethical leaders that can move their constituents to actively engage this diversity in constructive and meaningful ways. This is particularly important in an age of increased polarization and resurgent intolerance and bigotry in the United States and elsewhere in the world.

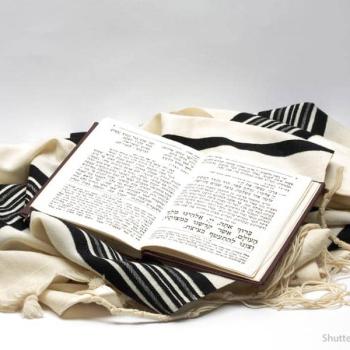

To help meet this urgent challenge, in the days following MLK Day, Hebrew College piloted a new week long seminar for future Jewish leaders—rabbis, cantors, and educators—entitled “Leadership for a Pluralistic Age.” The name was inspired by Dr. Diana Eck’s insight that while “diversity” is a fact of life, “pluralism” is an ethos we must consciously cultivate. The program involved intensive courses in Christianity, Islam, and intra-Jewish and interreligious engagement, meetings with spiritual and civic leaders involved in bridge-building efforts, outings to local religious and cultural institutions, and a communal exploration of a related photographic exhibit.

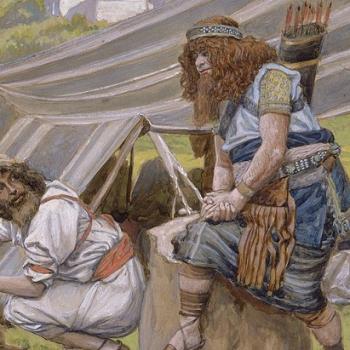

The goal of this educational undertaking was not to erase or even minimize our differences, but to help students hold the tension of our universality and particularity with greater cognizance and confidence. This is rooted in the foundational notion that all human beings are created in the “Divine image” (Genesis 1:26-27) and that each person is a unique creation. As Dr. King’s close friend and colleague, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, once asked rhetorically, “When engaged in a conversation with a person of different religious commitment, if I discover that we disagree in matters sacred to us, does the image of God I face disappear?”

As Rabbi Heschel understood well, this does not mean that we need to accept all ideas or opinions as equally valid, but that we must treat people humanely. It also suggests that before we rush to debate or protest—both of which are vital in a healthy democracy (as Dr. King modeled for us so powerfully)—we must to learn enough about the “other” to know if and why we disagree with them. This recognition should also be accompanied by a healthy dose of humility, knowing that no one possesses ultimate truth. In fact, in a world in which there is so much that we don’t know, we would be wise to learn from as many people as possible (even those registered with the “wrong” political party). While we may all be created in the Divine image, none of us is God.

Heschel made his statement about the sanctity of the human face as part of an address he gave in 1965 at Union Theological School (a Protestant institution), where he was serving as a visiting professor. The title of his speech was “No Religion is an Island.” Like MLK, he understood that we live in one, inescapable, “world house.” The great challenge is to learn how to move between the separate and shared spaces in this expansive home with dignity, integrity, and compassion. The recent pluralism initiative at Hebrew College was but one modest attempt at living into this grand vision.