2 Peter 3 is a well known passage concerning the Day of the Lord. A vision of the judgment to come and the effect this judgment will have on creation. Scoffers doubt that the end will come, and focus on their own evil desires. 2 Peter warns the reader…

well known passage concerning the Day of the Lord. A vision of the judgment to come and the effect this judgment will have on creation. Scoffers doubt that the end will come, and focus on their own evil desires. 2 Peter warns the reader…

But they deliberately forget that long ago by God’s word the heavens came into being and the earth was formed out of water and by water. By these waters also the world of that time was deluged and destroyed. By the same word the present heavens and earth are reserved for fire, being kept for the day of judgment and destruction of the ungodly.

…

But the day of the Lord will come like a thief. The heavens will disappear with a roar; the elements will be destroyed by fire, and the earth and everything done in it will be laid bare.

Since everything will be destroyed in this way, what kind of people ought you to be? You ought to live holy and godly lives as you look forward to the day of God and speed its coming. That day will bring about the destruction of the heavens by fire, and the elements will melt in the heat. But in keeping with his promise we are looking forward to a new heaven and a new earth, where righteousness dwells. (3: 5-7, 10-13, NIV)

On the surface this passage is hard to reconcile the vision of Paul, that all creation is waiting in eager expectation for the day when it will be liberated and brought into freedom and glory.

Jonathan Moo and Robert White, Let Creation Rejoice: Biblical Hope and Ecological Crisis, dig into this passage. Why should creation rejoice given the end portrayed by Peter?

First we need to consider the form and context of the text. Like Paul, the author of 2 Peter is borrowing from the Old Testament, from the Prophets, and especially from the apocalyptic passages (think Daniel and Ezekiel as well as other passages scattered throughout the prophets) that “employ dramatic imagery to portray the salvation and judgment of God.” This isn’t a prediction that we should read like a historical narrative.

Like much of biblical prophecy 2 Peter 3 describes events that transcend ordinary human experience, and only metaphor, poetry, and the language of apocalypse are adequate for the task. … Peter simply is not concerned with instructing us about the physical structure of the universe; his dramatic portrayal of the coming of God to his creation is meant instead to transform the way we live and act in the world today. (p. 119)

Certainly 2 Peter intends to depict a real future judgment, but the language is the language of apocalypse. Moo offers two slightly different approaches to this passage, possibilities arising from the ambiguity of the language, but both with the same end result.

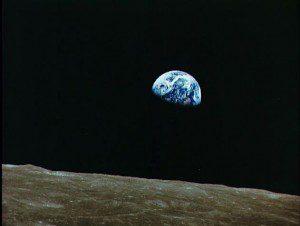

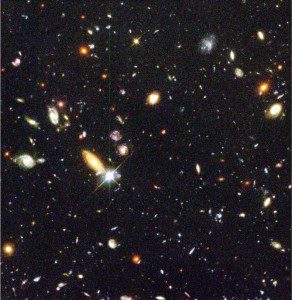

The heavens will disappear with a roar. Verse 12 talks about the destruction of the heavens by fire. However, this doesn’t refer to the disappearance of the universe as we know it, the stars, planetary systems, and galaxies revealed by telescopes with sensitive cameras studied by astronomers and astrophysicists. Neither the author nor his audience knew anything of this. Rather, the picture in their minds was of the heavens as the realm of God and his angels.

The heavens will disappear with a roar. Verse 12 talks about the destruction of the heavens by fire. However, this doesn’t refer to the disappearance of the universe as we know it, the stars, planetary systems, and galaxies revealed by telescopes with sensitive cameras studied by astronomers and astrophysicists. Neither the author nor his audience knew anything of this. Rather, the picture in their minds was of the heavens as the realm of God and his angels.

Given that God is envisioned as enthroned in his transcendent “heaven” above (2 Pet 1:18; 1 Pet 3:22), this burning away of the earthly “heavens” suggests that the symbolic separation between God and his creation is being done away with; the earth is about to be visited by its Creator, Judge, and Redeemer. (p. 120)

The elements will be destroyed by fire. Verse 12 echoes this with the elements melting in the heat. The elements here (Gk. stoicheia) may refer to the elements of the cosmos as the Greeks and Romans understood them: water, air, earth, and fire. But they don’t refer to the atoms we study, describe, and manipulate as chemists. This, in turn could refer to the burning up of the entire world. However Moo points out that the NIV translation “since everything will be destroyed in this way” misses a word and the NRSV is more accurate “since all these things are to be dissolved in this way,” a wording followed as well by the ESV “since all these things are thus to be dissolved.” The phrase “these things” may have a more limited referent than implied by the NIV’s use of “everything.”

In any case, it is important to note that the “destruction” of the elements or “all (these) things” would not have meant for the ancient readers the dissolution of the world into nonexistence. The language of “destruction” is used in the Bible to describe something that has been rendered unfit for its purpose … The idea is of something wrecked, ruined, broken apart or put beyond human use, not of something having been obliterated into nothingness. (p. 120-121)

But there is another possibility as well. The elements may not refer to the material earth at all. The elements may refer to heavenly bodies; stars, sun, moon, possibly even evil “heavenly” spiritual forces.

A number of scholars have thus argued that Peter is describing here, not the melting of the earth but the destruction of heavenly “elements” prior to God’s judgment of the earth. The idea expressed in 2 Peter 3:10 would in this case echo Isaiah 34:4 where an ancient Greek translation describes God’s judgment as a time when “all the powers of heaven will melt.” (p. 121)

2 Peter may be describing a progression:

(1) the outer heavens are torn away, (2) the intermediary heavenly bodies are dissolved with fire, and then (3) the earth itself and all the things done in it are laid bare before God, being “found” before him. There is no longer anything left to separate or hide human beings from the testing fire of God’s judgment.

Peter is using vivid cosmic imagery in this passage to convey the common biblical idea that on the last day there will be nowhere for anyone or anything to hide from God’s judgment. (p. 122)

Everything done in it will be laid bare. The focus of 2 Peter isn’t on the earth or creation, but on human evil and the judgment of the ungodly. God’s judgment is sure and certain.

Peter’s “positive vision of the future” is “a new heaven and a new earth” (2 Pet 2:13). But Peter is keenly aware that it is only through the unmasking of human injustice and its judgment by God himself that this place “where righteousness dwells” can ever be realized. (p. 123)

The image of cosmic apocalypse is intended to drive home this point. There is nowhere to run, no place to hide. The fire will test everything – as Paul puts it “the fire will test the quality of each person’s work.” (1 Cor. 3:13)

What kind of people ought we to be? We should avoid the way of the scoffers and live in the light of God’s coming judgment. We should resist the temptation to live for ourselves alone, satisfying our appetites and desires. Making every effort “to be found spotless, blameless and at peace with him.” v.14 Peter suggests that we may even be able to speed the day of the Lord’s coming through such living. We should live today with the virtues of the new creation, that place where righteousness makes its home.

Coming back around to the topic of their book – ecological crisis – Moo and White suggest that this means genuine self-control.

What will it mean for us to exercise genuine self-control, not only in our sexual lives (so often the exclusive focus of our teaching) but also in our economic lives, in how we do business, in what we consume and in what we choose not to consume? What will we decide is “enough” if we truly accept that God has given us all we need and that he desires us to reflect his generosity in how we live among our fellow creatures? (p. 128)

And two powerful challenges:

If we miss the the power of these texts to destabilize our comfortable lives and to reshape us into Christlike people who are prepared to follow in the way of the cross, to enter into self-sacrificial work on behalf of our neighbors around the world and of an entire groaning creation, we have truly become “ineffective and unproductive” in our knowledge of the Lord Jesus Christ (2 Pet 1:8). (p. 128)

This isn’t about waiting for the destruction of the present world, consuming it as we go … looking to some disembodied existence or a to a brand new universe.

The challenge to 2 Peter’s readers is to live now, in the present, as members of that community of peace, as those who have entered already into God’s shalom even as we await the coming of our Lord and the fullness of the new creation that will accompany his coming. (p. 129)

2 Peter 3 challenges us to be aware of the coming judgment, to live accordingly. There will be a radical setting to right of the world and everything in it. This is not a pass to consume a world set for destruction anyway, but a call for faithful transformation to be the people of God.

Which is the better interpretation of 2 Peter 3? Cosmic catastrophe or a prophetic warning of the judgment to come when all will be laid bare before God?

How does this passage make sense in the context of the rest of the New Testament?

If you would like to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.