When I started this series on creation care I received an e-mail questioning the wisdom of diving into the topic. For many creation care is synonymous with climate change or global warming. This is a political hot potato. Unlike evolution, where we evaluate evidence in existence and consider physical models to interpret the data, the concern with climate change rests substantially on extrapolation into the future. Our models are improving, but far from perfect. This makes extrapolation somewhat risky. Of course, this doesn’t mean we should ignore the issue or regard it as an illusion. Frankly, the potential consequences are far too great. It does mean that a modicum of intellectual humility is appropriate. It isn’t all extrapolation, however. There is very real evidence for our concern.

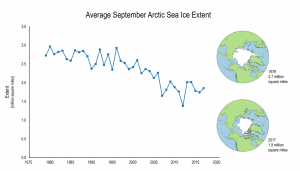

Jonathan Moo and Robert White in Let Creation Rejoice: Biblical Hope and Ecological Crisis. are unequivocal about this: human activity is changing the global climate, period. They find the evidence to be undeniable and inescapable. They are also quite clear that they view this to be a serious problem that will harm humans, especially the weak and the poor. They are less certain about other aspects – whether we have or have not crossed a tipping point, how big the effects will be, and what specific measures should be taken. They present a number of lines of evidence for their view – one of which is the declining arctic sea ice extent in September when it is at a minimum each year. The overall decrease between 1979 and 2017 is approximately 30%. There is a decline for every month of the year, but the effect is largest in the heat of summer. There was a rebound after a record low in 2013, but it doesn’t appear that the general downward trend has changed. The image here is from globalchange.gov.

Jonathan Moo and Robert White in Let Creation Rejoice: Biblical Hope and Ecological Crisis. are unequivocal about this: human activity is changing the global climate, period. They find the evidence to be undeniable and inescapable. They are also quite clear that they view this to be a serious problem that will harm humans, especially the weak and the poor. They are less certain about other aspects – whether we have or have not crossed a tipping point, how big the effects will be, and what specific measures should be taken. They present a number of lines of evidence for their view – one of which is the declining arctic sea ice extent in September when it is at a minimum each year. The overall decrease between 1979 and 2017 is approximately 30%. There is a decline for every month of the year, but the effect is largest in the heat of summer. There was a rebound after a record low in 2013, but it doesn’t appear that the general downward trend has changed. The image here is from globalchange.gov.

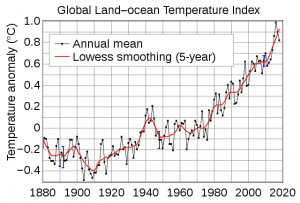

Moo and White also include a plot of three different global average temperature records created independently. The NASA average (one of their three but updated through this year) is plotted to the right – image from wikipedia. The other two follow the same trend.

Moo and White also include a plot of three different global average temperature records created independently. The NASA average (one of their three but updated through this year) is plotted to the right – image from wikipedia. The other two follow the same trend.

It is important, of course, to ask if these changes are “natural” or the result of human activity. There are, after all, natural fluctuations in the earth’s temperature resulting in periodic ice ages and periods of warming. In fact, it has been warmer at times in the past than it is today. The recent changes, however, are far too persistent and the turn-on was too sharp to be accounted for by known natural mechanisms unrelated to human activity. “But when the greenhouse gases produced by humans are added, the agreement between the models and the observed temperature record is much closer. … This is a potent indication that humans are responsible for the rapid temperature increase since preindustrial times.” (p. 66-67)

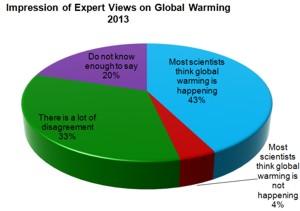

Why is there so much skepticism? Moo and White point to six contributing factors. The first is that climate is a long-term average phenomenon, yet we experience weather on a day-to-day and year-to-year basis. It is hard for the average person to grasp the changes or the potential consequences. The media also plays a role by giving equal time to opposite sides of the debate. Open discussion is good, and should happen in the media, but because the format tends to feature one supporter and one skeptic the audience comes away with the impression that there is a great deal of disagreement in the scientific community in general and among climate scientists in particular. The pie chart illustrates the public impression (data from The Yale Project on Climate Change). In reality there is a strong consensus among climate scientists on the issue, but not unanimity.

Why is there so much skepticism? Moo and White point to six contributing factors. The first is that climate is a long-term average phenomenon, yet we experience weather on a day-to-day and year-to-year basis. It is hard for the average person to grasp the changes or the potential consequences. The media also plays a role by giving equal time to opposite sides of the debate. Open discussion is good, and should happen in the media, but because the format tends to feature one supporter and one skeptic the audience comes away with the impression that there is a great deal of disagreement in the scientific community in general and among climate scientists in particular. The pie chart illustrates the public impression (data from The Yale Project on Climate Change). In reality there is a strong consensus among climate scientists on the issue, but not unanimity.

There is some distrust of the experts. The 2009 hacked “climategate” emails didn’t help matters in this regard. Nor does the tendency to hubris among too many scientists and the expectation that the general public should simply shut up and believe the experts. Scientists can also be rather poor at explaining their results in a way that the lay public can understand.

Both of these things must change [hubris and lack of clear explanation], because the public needs to own the results and to be carried along with the scientists if they are being asked to sign up to hard and perhaps costly changes. (p. 76)

Moo and White also point to deliberate misinformation by large corporations with much to lose in the short term. This can be compared to the long effort by tobacco companies to cast doubt on the dangers of smoking.

Finally – it is easier to do nothing than something; especially when there is no owned sense of urgency. Loud, pessimistic pronouncements by activists and climate scientists do much harm here. Even if the alarmists are right, they won’t move the mountain of opinion and get the necessary action this way. The public has to own and buy into the need, it can’t be imposed upon them.

What next? Moo and White argue (and this will be the focus of the rest of the book) that appropriate Christian response is deliberate action. We can’t just sit on our hands and do nothing.

If we are truly to love our neighbor as ourselves, as Jesus commanded us to do, then those of us in the high-income countries that historically have caused global climate change through our emissions of greenhouse gases have to take account of the effect of our actions on our neighbors and on all life on earth. Those neighbors may be invisible to us, either because they live in faraway places such as southeast Asia or sub-Saharan Africa, or because they are not yet born. Yet, given what we now know about the consequences of our actions, our responsibility toward them remains. We enjoy a high standard of living largely because of our burning of fossil fuels both today and over the past century or more. So we have a responsibility to help those affected by this to adapt to their changing circumstances and to do what we can – individually, communally, politically – to stop wreaking such damage, to try to prevent the worst-case scenarios climate scientists warn us about. (p. 79)

I expect that there will be some discussion about appropriate actions, but the primary focus of the remainder of the book will be the development of a biblical and theological case for action. The irony is that we, as Christians, should be at the forefront of a movement to care for others and to act responsibly; yet we tend to be among the most skeptical and least concerned to engage in the issues.

Are you convinced that humans are causing a change in the global climate?

What would convince you?

If we are changing the global climate, what should we do about it?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail [at] att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.