One of the most interesting insights is the nothing new under the sun phenomenon, at least when it comes to human nature. We’ve been working through Craig Allert’s new book Early Christian Readings of Genesis One. Several years ago I read and posted on Peter Bouteneff’s book Beginnings: Ancient Christian Readings of the Biblical Creation Narratives. In this book Bouteneff looks at several of the early church fathers including the Cappadocian Fathers, Basil and the two Gregories, Gregory of Nazianus and Gregory of Nyssa, Basil’s brother … as well as Cyril of Jerusalem and Athanasius. In this post we will look at Athanasius and at Basil and their focus when it comes to the interpretation of the early chapters of Genesis. What follows is a lightly edited repost from our original series on Bouteneff’s book as I enjoy the Florida sunshine visiting family.

The Nicene council of 325 AD was driven by controversy surrounding the views of Arius, the nature of Jesus, and the Trinity. Athanasius (ca. 298 – 373) was at the council as a young man (probably between 27 and 29) and the shadow of Arianism impacted his approach for five decades. Basil (ca. 330 – 379) is truly post-Nicene, but the Arian controversy still loomed large throughout his lifetime.

The Nicene council of 325 AD was driven by controversy surrounding the views of Arius, the nature of Jesus, and the Trinity. Athanasius (ca. 298 – 373) was at the council as a young man (probably between 27 and 29) and the shadow of Arianism impacted his approach for five decades. Basil (ca. 330 – 379) is truly post-Nicene, but the Arian controversy still loomed large throughout his lifetime.

Athanasius used Genesis 1 to emphasize creation out of nothing. The creation of heavens and earth is contrasted with the timeless begetting of the Son. Athanasius was not entirely consistent in either his concept or presentation of Adam. God created Adam with his coeternal Son. Adam was the beginning of the universal genealogy and the lineage of Christ. Clearly Athanasius saw Adam a a unique individual the first created at the genesis of the human race. But … he did not see in Adam the cause for all human pain and suffering, the one who sidetracked God’s perfect creation. Bouteneff summarizes that for Athanasius “he was also the first sinner, although he did not determine the sin of subsequent generations.“

Athanasius also saw in the pre-fall Adam and indication of the age to come. It is here, however, that Bouteneff finds him less than consistent. The pre-fall state could be one of purity and communion with God. In another place he contrasts it with the age to come. In the context of his oration against Arian brings in the condition of mankind:

Mankind then is perfected in Him and restored, as it was made at the beginning, nay, with greater grace. For, on rising from the dead, we shall no longer fear death, but shall ever reign in Christ in the heavens. And this has been done, since the own Word of God Himself, who is from the Father, has put on the flesh, and become man. (Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (NPCF) 2-04. Athanasius: Select Works and Letters p. 385)

Bouteneff has a more recent translation – but the idea remains the same. Adam lived under the threat of death even in his pre-fallen state, but in the resurrection we will no longer fear death for death has been overcome. Exactly how he portrays the pre-fallen Adam however is “anything but consistent.” Adam was bodiless and pure through grace, or embodied but free from sensual and and bodily things … the kinds of things one must contemplate if one mulls over a pre-fall state.

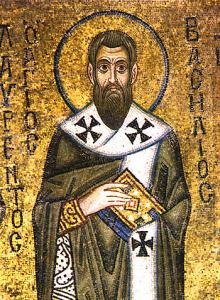

Basil the Great also known as Basil of Caesaria was baptized in the late 350’s, began writing in the early to mid 360’s and died January 1, 379. He was born in, and became bishop of, Caesaria Mazaca in modern day Turkey. Basil wrote and delivered a series of homilies on the Hexaemeron, the days of creation. An old translation is readily available in NPNF2-08 Basil: Letters and Select Works.

Basil the Great also known as Basil of Caesaria was baptized in the late 350’s, began writing in the early to mid 360’s and died January 1, 379. He was born in, and became bishop of, Caesaria Mazaca in modern day Turkey. Basil wrote and delivered a series of homilies on the Hexaemeron, the days of creation. An old translation is readily available in NPNF2-08 Basil: Letters and Select Works.

According to Bouteneff, Basil in common with others of his era used “Scripture either inside or outside its original context, interpreting it typologically or literally, and perhaps most often employs it paraenetically – to make a moral point.” (p. 127) and a bit later commenting on Gregory’s funeral oration for Basil … “But what the Greek actually says is that Basil leads us away from seeing either exclusively literally or spiritually; he takes us further from depth to depth.” (p. 127) Basil took scripture and the inspiration of scripture very seriously – but this did not lead to a wooden literalism as the clear meaning. There is a multifaceted nature of scripture.

Genesis 1 for Basil is about God, and about how we should live – it is not about science or specifics of the nature of the universe. To give just a taste, the first homily is on this alone “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.”

The philosophers of Greece have made much ado to explain nature, and not one of their systems has remained firm and unshaken, each being overturned by its successor. It is vain to refute them; they are sufficient in themselves to destroy one another. Those who were too ignorant to rise to a knowledge of a God, could not allow that an intelligent cause presided at the birth of the Universe; a primary error that involved them in sad consequences. … Deceived by their inherent atheism it appeared to them that nothing governed or ruled the universe, and that was all was given up to chance. To guard us against this error the writer on the creation, from the very first words, enlightens our understanding with the name of God; “In the beginning God created.” What a glorious order! He first establishes a beginning, so that it might not be supposed that the world never had a beginning. (NPNF2-08 p. 53)

…

Do not let us undertake to follow them for fear of falling into like frivolities; let them refute each other, and, without disquieting ourselves about essence, let us say with Moses “God created the heavens and the earth.” … Because, although we ignore the nature of created things, the objects which on all sides attract our notice are so marvelous, that the most penetrating mind cannot attain to the knowledge of the least of the phenomena of the world, either to give a suitable explanation of it or to render due praise to the Creator, to Whom belong all glory, all honor and all power world without end. Amen. (NPNF2-08 p. 58)

The science of Basil’s age came into conflict with the Christian view of creation. But the conflict, where he saw it, was not in the scientific details. The essence and nature of created things was not really the point – not to Basil in the fourth century or for us today. The real conflict was in the metaphysics that drove the use of the science … they could not allow an intelligent cause … nothing governed or ruled … all was given up to chance. The real conflict today remains the same.

Bouteneff summarizes his discussion of Basil’s Hexaemeron focusing on two main themes. For Basil the primary message of creation as told in Genesis 1 is about the Creator, the Craftsman. It is not about creation per se. Moses, and Basil certainly thought Moses wrote Genesis, focused on God as Creator to render due praise to the Creator. The secondary message is rhetorical and moral. Basil draws lessons for his audience from the text. He likens the gathering of waters to the gathering of people in the church, the plants lead us to contemplate people and to embrace our neighbors. Animals provide examples we should either shun or emulate. The two main themes can be distilled: Love God – Love Others.

Basil did not comment much at all on Adam. He was not interested in Adam as the origin of sin and even in his homily “On Why God is Not the Cause of Evil” Adam receives but brief mention. Basil was preoccupied with personal freedom and responsibility. We don’t sin because of Adam, we each fail of our own volition. Basil did not consider an action “sinful” unless done consciously and voluntarily. When he commented on Genesis 2-3 his focus was not on sin but on salvation. He jumps from creation to salvation in the fullness of time, when the only begotten Son, the one through whom the ages were made, took on flesh and dwelt among us. He leans heavily on Romans 5, 1 Cor. 15, and Col. 1.

Basil, like those who came before him, was Christ-centered in his interpretation of scripture including his interpretation of the paradise narrative.

What do you make of Basil’s focus on God and on how we should live?

What can we learn from Basil’s approach in the light of the science and atheism of his day?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail [at] att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.