By Leslie Leyland Fields

My husband’s running for state office right now. I’ve kissed babies, shaken hands, handed out fliers, waved in a parade, edited op-eds. This national election cycle has become personal in unexpected ways. When the nation goes to vote on November 8, the fate of our own lives here in Kodiak, Alaska for the next several years will be decided as well.

But there the parallels end. My husband is not calling for Alaska to return to some former “greatness.” I don’t recall him using that overused word even once. But it’s the adjective de rigeur in this election cycle. Even Obama has used it.

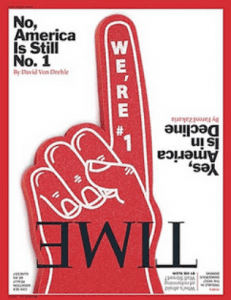

In one of his State of the Union address this last year, he assured us that we’re “still the greatest nation on earth.” Earlier this year, most of the Republican candidates endlessly recited the president’s damages to that claim, and promised they would restore our nation to its former glory and make American great “again.” Trump was not the only one. He was the loudest, though, and he and his slogan prevailed. (The phrase is not new, of course. Bill Clinton used it repeatedly 1991 and 1992 in his own race to the White House and then used it again in a campaign ad for Hilary in 2008.)

But the patriotic phrase, cue flag-waving and hat-tossing, deserves at least one question:

Yes, American is beautiful but Why must America be great?

Let me qualify: I might accept this aim toward “greatness” if the adjective were exercised in its dictionary sense of “an extent, amount, or intensity considerably above the normal or average.” Who doesn’t want to live in a country “considerably above average”? But its connotative meaning is much closer to the Mohammed Ali sense of “I am the greatest!” which is beyond the reasonable goal of becoming again an estimable nation. Interestingly, our American exceptionalism, which used to be a purely Republican trope, has crossed party lines. Michelle Obama pronounced recently, “This right now is the greatest country on earth.” Hilary’s in on it too. At the American Legion National Convention in Cincinnati, in August, Clinton said, “The United States is an exceptional nation. It’s not just that we have the greatest military, or that our economy is larger than any on Earth, it’s also the strength of our values.”

Why must we be the “greatest country on earth?” Or, more accurately, why must we believe we are the “greatest country on earth,” superior to the 195 others?

Why must we be the “greatest country on earth?” Or, more accurately, why must we believe we are the “greatest country on earth,” superior to the 195 others?

Aside from the political posturing, each side driving in their stake for votes, it’s the lamentable human condition.

Remember the day that twelve men walked a dusty road, arguing? They were famous. They could touch a broken leg and heal it, they could pray over an afflicted woman and stop her hemorrhage. They could restore a little boy’s hand, burnt in a fire, back to wholeness. They could even touch a dead body and lift it to life, on occasion. Big stuff. Crowds followed them. They were wildly popular. People hushed when they spoke, cheered when they healed.

They kept a record, each one of them, secretly: how many healings, how many exorcisms, how many hands shaken and babies kissed and cripples running races. But they couldn’t keep it quiet.

“So, how many you got there, John, buddy? I’ve had three raisings from the dead. Not to brag or anything, but that’s pretty great, I’d say. ”

“Really? I took a poll in that last city and I’m definitely on top. They wanted to make me mayor!”

“Mayor! That’s nothing!” scoffed Andrew. “The Zealots want to make me president! I cured a whole colony of lepers!”

And so it went.

In their bickering and bragging, they even forgot about Israel, which was why they got into this campaign in the first place. They were all looking for a Messiah who would set Rome on fire, who would rout their political and religious oppressors and restore Israel to power and supremacy again. “Make Israel Great Again!” That was what they signed on for.

But, full of miraculous healings, pride and applause, even that heady slogan was lost. Ultimately, it came down to them. To each one of them vying against the other.

Aspiring to “Greatness” does that.

They were wrong about everything that day. Jesus didn’t come to do any of that. The power Jesus granted was the power to forgive, the power to humble the proud, the power to be as pure-hearted and dependent upon God as a child. The little girl or boy he pulled into their midst made that clear. “Truly I tell you, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.” Jesus didn’t end there. He clarified what aspect of that child we need to emulate: “ . . . whoever takes the lowly position of this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven.”

And later, “Whoever wants to be great among you must be your servant.”

And later, “Whoever wants to be great among you must be your servant.”

My husband and I are lucky. In our town and state, we’re not tempted to claim either present or former “greatness.” Our goals are more modest. We’re just trying to serve the people in our district and balance the budget of a state that’s going bankrupt. If my husband should win, there won’t be confetti and national headlines; we won’t be dressing in designer clothes, dancing at a lavish ball to celebrate. We’ll be working, often in remote villages, riding around in skiffs, wearing rubber boots and raincoats.