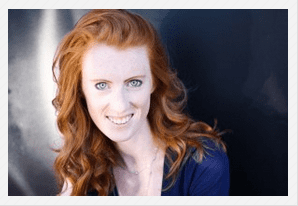

This review is by a person who has thought about the topic and by a person to whom John Mark Comer has written his book, Loveology. The review is by former student, Kellie Carstensen, who led a student group that met in my office routinely to discuss relationships and love.

When Traditional Meets Trendy: John Mark Comer’s Loveology

John Mark Comer’s new book Loveology presents a remarkably comprehensive theology of love in the context of marriage, dating, and the male-female relationship. Starting with love and working backwards through marriage, sex, romance, and then the male-female dynamic, Comer contributes a youthful, pastoral voice to the conversation on Christian sexuality which is unique alongside his more conservative foundational beliefs.

The book’s format and design evoke a simplified aesthetic similar to a Rob Bell book where white space is prevalent and each chapter begins with a contrasting pink page using white ink. Comer’s writing style is boldly informal as it confronts the reader with direct questions, fragments sentences, and creates a more dramatic tone through choppy paragraphs that are easily readable for an audience oriented towards tweet-sized texts. These elements, in addition to the content itself, signify what is stated on the back cover: “this is a book for singles, engaged couples, and the newly married” who want to learn about a Christian interpretation of love and sexuality. Even so, for readers who have been married a long time this book provides a window into the conversation among younger Christians about sex and common questions raised by present culture.

Regardless of the reader or the trendy cover, there is an underlying argument in the book that has strong traditional roots. The book begins as a safe, typically affirmed discussion on Christian love based on the sacrifice of Christ, marriage that is a serious choice, and sex as healthy within the confines of marriage. In these areas Comer establishes his relatable, trustworthy character as he shares parts of his own personal story. None of it is likely to get people boiling. However, the final sections on “male and female” and “gay” reveal the more controversial elements of Comer’s beliefs about gender roles. To a younger audience these are the areas with the most gray areas, and thus they are the areas that Loveology has the hardest time successfully explaining (or convincing).

So what is love?

Loveology begins by calling for a redefinition of love in the midst of cultural romance myths and a declining respect for love as more than just a thing or an emotion that happens to us. Instead, Comer argues the core of love is defined by the sacrifice made by Jesus Christ on the cross and thus love is primarily about the active choice of self-giving for another (35). His argument is well grounded in Scripture and would be widely approved of by many Christians.

Along these lines, the section on marriage dispels the prevalent myth that the purpose of marriage is to make you happy. Instead, “happiness is the result of a healthy marriage” (75). Marriage by God’s design is a partnership of two people who can use it as a means to succeed in kingdom work for God.

In regards to sex, Loveology also cautions readers to remember the purpose of sex to fuel the intimate bond in marriage of two people becoming one. Sex is not just about the physical act itself, but instead the true purpose of the act reveals why it is destructive outside of marriage and life-giving inside of marriage. In the section on “Romance” Comer outlines four marks of a healthy relationship based on the Song of Songs. And similar to many Christian books on the subject, this is where the “line” becomes fuzzy.

It isn’t that simple

The challenge with any book on such a heated topic is finding a middle line between over simplifying love or over complicating it. Although Loveology is trying to walk this line, it often fails to do so without sounding contradictory. The temptation to simplify is understandable when speaking to a younger audience that wants easy answers. Yet, as with many aspects of Christian belief and practice, the answers are rarely simple.

Early on Comer states that “Love = Jesus on the cross. There you have it, in black-and-white” (33). This in itself is far from blasphemous, but the tension arises not long after when he writes “It’s that easy. And that difficult” (36). At this point the reader might already be confused. Is it black-and-white? Or does the difficulty acknowledge gray area? And gray areas are the primary arena for questions on the topics surrounding love and sexuality. These gray areas are where controversy breeds.

Here comes the controversy

Over-simplification rears its ugly head again in the section on male and female. Comer, in arguing for a framework of gender roles where the man is called to be the leader, states:

“It’s that simple. Controversial, divisive, incendiary, yes–but simple. The man was made to lead, and the woman to be his partner, right at his side.

But notice how vague the ‘roles’ are.” (183)

I applaud Comer for trying to balance the complexity of the issue, but anytime someone says “it’s that simple,” it usually isn’t simple at all. He acknowledges it in the next line by saying the roles are vague, but at this point we are again left mid-conflict between a supposedly simple thing and something that is also incredibly vague.

Comer’s beliefs on gender roles lean toward the complementarian perspective. Although this is widely accepted by many Christians, the younger audience that Comer is addressing will most likely find it somewhat alarming amidst a culture with growing respect for the feminist and egalitarian perspectives. At the end of the section he again secedes to the complexity of the issue by saying the “gender roles are more a trajectory than a list of do’s and don’ts” and he also admits that this position does not fit in with the forward-thinking, progressive culture of today because Christianity is supposed to transcend culture (185). Even so, Comer does not say much about the challenges of this trajectory or how to balance the complexities before it derails into unhealthy relations between men and women, which has often been the case throughout history.

Comer’s definition of “leading” is also contradicted in several spots. Initially he says Adam was called to lead, and “by ‘lead’ I mean ‘give your life away for the good of another’” (182). But then in the next chapter, he looks at Paul’s letter to the Ephesians and explains that the word “submit,” or hypotasso in Greek, “can be translated ‘respect’ or ‘yield’ or ‘defer’ or ‘put another’s good ahead of your own’” (189). If men are called to lead, or give their life away for the good of another, and women are called to submit, or put another’s good ahead of their own, how are those two things different? According to Comer they are separate, but the gray area is deep enough for a reader to get lost in.

To be clear, I am not saying that I either agree or disagree with Comer’s stance. As a millennial caught up in the gray areas of life in general, I am open to every point of view. However, as Christians we need to be aware of how frustrating it can be, to both believers and unbelievers, when an argument is over-simplified, then contradicted, and then acknowledged as vague, but then simplified again as “biblical truth.”

Remarkably, the section on “gay” embraces the nuances of gray areas better. Comer admits that this issue “isn’t about politics” to him, but rather “it’s about people” (213). Although he again settles on the more “traditional” side in his belief that God’s vision of marriage and sexuality is solely between a man and a woman (215), Comer also acknowledges the way that Christians have made this into a damaging and hurtful position in present society. By spending the bulk of the chapter dispelling myths about sexuality from both sides, Comer better engages the gray area between the two extremes while maintaining a scripturally-based defense for his position against homosexuality.

Still happily ever after

Although Comer struggles to walk the line between simplistic and complicated, Loveology as a whole is worth reading because of the way it comprehensively attends to the range of issues concerning love and sexuality. Most of the recent evangelical books on these topics have focused on one area of sex, marriage, or the relationship between genders. In comparison, Loveology successfully covers all of these areas in a thorough manner that engages with scripture as well as present culture. Comer contributes to the discussion as a youthful, pastoral figure who is still rooted in traditional Christian thought. Of course, this unique approach should not be read blindly or without caution. After all, the counter-cultural Christian knows love isn’t really blind, it is patient and kind while we work out the nuances of all that is gray.