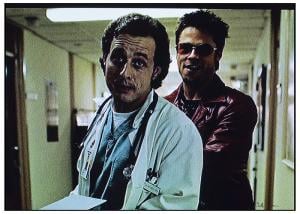

Source: Flickr user Seth Anderson

License

There’s really no way to “review” Fight Club (1999), a movie at this point so famous and so abundantly discussed that it belongs more to the pages of an Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson book than to my blog. Fight Club is the harbinger of the Trumpian right. Fight Club is the toxic man’s mainstay. Fight Club is a pretty dang good movie. Fight Club is the pit in the American stomach. What more is there to say?

Yesterday, for an upcoming project I’m working on with a friend, I had a blast interviewing Matthew Specktor, co-founder of the LA Review of Books and executive at 20th Century Fox when they made the film. He emphasized how cheaply the film was optioned. He told of how, without Brad Pitt and David Fincher falling in love with the script, it never stood a chance. Specktor informed me that the premiere at the Venice International Film Festival involved some boos. Here we have an iconic, even defining, piece of 90s cinema. It stands as the supposed embodiment of so much, and yet it meant nothing to the cultural arbiters of that moment. The Adbusters-rich masculine cry, “we are the middle children of history” didn’t land.

Audiences didn’t head out in droves to see it either. Despite opening at number one, it underperformed its initial revenue target. The debacle even contributed to the resignation of executive Bill Mechanic. Hordes of KoRn-listening, JNCO-jean wearing middle-American roughnecks stayed home. The culture, so soaked in Fight Club, was too saturated to accept the thing itself.

An object like Fight Club, it seems to me, is the lens through which we make sense of a moment looking back at it. It seems the kind of film that so successfully captures the feeling of a period that that period cannot but reject it. We remain, I fear, stuck as the “middle children” of history. In this sense, we have not yet gotten beyond Fincher’s film.

Now, everything buzzes with politicization and polarization. Yet our politics feel as “anti-political” as the hodgepodge that is Project Mayhem. If Tyler Durden and his acolytes only go to bars to fight in their basements, we don’t even go to bars. When we laugh at Edward Norton talking abut defining himself based on the things he owns, we can do so only because we have made an uneasy peace with our fixation on “treats.” If we recognize an undifferentiated male rage in the movie, we can only frown in recognizing its many developing tendrils in our own time. Our edgelords still try to be transgressive. This moment’s wisdom remains pop stoicism and a warlike monkish-ness. Less has changed than we’d like to think.

I suppose what I’m talking about the end of history. This is the long spiritual death that it first seemed would accompany long-term material prosperity. Now it seems likely only to intensify as life in the United States gets more financially difficult. Whether we ascribe the quote to Jameson, Žižek, or Mark Fisher, the end of the present cannot take form anymore clearly than then. Matters are worse, sure. But no less psychically suffocating.

We feel forgotten by history itself, its middle children through and through, undelivered from our affliction. Fight Club was unrecognized in its time. Now it is a mirror, if a cracked, an imperfect one. I’m glad I took another look.