When I’m down, I always turn to Ecclesiastes. Without fail, the wisdom of Qoheleth becomes what in the 90s people called Chicken Soup for the Soul. But, unlike such self-help books, Ecclesiastes doesn’t talk up existence or tell me to buck up; no, it lays out the ways of the world before my eyes. It says: “this is how it is, and it ain’t great, but it’s what we’ve got. Disaffection is part of what it means to live, and, once you clear all the chaff away, sit down, eat your bread, and give thanks to God.” It practically starts with an upfront dismissal of all that we might think worth our time:

What profit have we from all the toil

which we toil at under the sun?

One generation departs and another generation comes,

but the world forever stays.

The sun rises and the sun sets;

then it presses on to the place where it rises.

Shifting south, then north,

back and forth shifts the wind, constantly shifting its course.

All rivers flow to the sea,

yet never does the sea become full.

To the place where they flow,

the rivers continue to flow.

All things are wearisome,

too wearisome for words.

The eye is not satisfied by seeing

nor has the ear enough of hearing.What has been, that will be; what has been done, that will be done. Nothing is new under the sun! Even the thing of which we say, “See, this is new!” has already existed in the ages that preceded us. There is no remembrance of past generations; nor will future generations be remembered by those who come after them. (1:3-11)

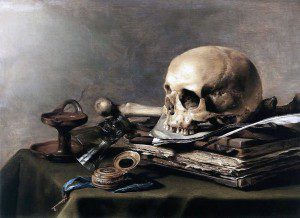

As with all wisdom, the point is so simple as to be easily forgotten. Everything, absolutely everything, you consider important, all the goods to which you lay claim—it’s all vanity. It all goes away when you die, and when you die, you’re forgotten. By the end of chapter one, Qoheleth has beaten you over the head with the ubiquity of vanity:

A bad business God has given

to human beings to be busied with […]

[I]n much wisdom there is much sorrow;

whoever increases knowledge increases grief. (1:13.18)

Not only is everything trash, but figuring that out—finding the truth—is a recipe for melancholy, for a seemingly interminable darkness. And just when you think the gnomic statements have gone far enough, the text goes on—it gives a kind of anatomy of desire by way of the things we typically desire. Witness just a few of the section headings on the USCCB website: “To Others the Profits” (Chapter 2), “No One Can Determine the Right Time to Act,” (Chapter 3), “Vanity of Toil” (Chapter 4), “Gain and Loss of Goods,” (Chapter 5), and “Limited Worth of Enjoyment” (Chapter 6): the list goes on and on, culminating in one of my favorite declarations:

Light is sweet! and it is pleasant for the eyes to see the sun. However many years mortals may live, let them, as they enjoy them all, remember that the days of darkness will be many. All that is to come is vanity.

Rejoice, O youth, while you are young

and let your heart be glad in the days of your youth.

Follow the ways of your heart,

the vision of your eyes;

Yet understand regarding all this

that God will bring you to judgment.

Banish misery from your heart

and remove pain from your body,

for youth and black hair are fleeting. (11:7-10)

Rejoice and follow your heart! But remember that God will bring judgment, and even if He does not—well, the preceding eleven chapters ought to have disabused you of the notion that all that glisters is gold. Be not miserable! Secure yourself against pain! But remember that everything you have been, are, and will be is dead, dying, and will die—in that order.

It beats you down, but it does not forsake joy—that is the seeming paradox of Ecclesiastes. Recognize how little it means, and then it will mean so much.

How? After he bludgeons you, Qoheleth ends with a bit of advice:

The last word, when all is heard: Fear God and keep his commandments, for this concerns all humankind; because God will bring to judgment every work, with all its hidden qualities, whether good or bad. (12:13-14)

If it all means nothing, and yet you feel the ineluctable desire to keep going on, there is nothing left but to keep the commandments: eat, love, pray (and here those words achieve their true meaning). To see the world as it is is not to be filled with hatred or anger—what Nietzsche called ressentiment; instead it is to give thanks for the very fact of being, to treat all things with justice, even as you know you can expect no justice in return. In short, it is to expect nothing, but to love it anyway, to love it for its very existence. There can be no time for gossiping or complaining; there is no use in becoming upset when things are “unfair” (because when all is vanity, what is fairness?). There is only the cold hard fact of being; there is only Ecclesiastes.