Yes, I know, rhetorical questions generally have the answer, “no,” and in this case, I’m referencing a Washington Post Wonkblog article, “Millions of jobs are still missing. Don’t blame immigrants or food stamps.” (Pet peeve: article titles that are multi-sentence.)

The article reports that

The share of Americans with jobs dropped 4.5 percentage points from 1999 to 2016 — amounting to about 11.4 million fewer workers in 2016.

At least half of that decline probably was due to an aging population. Explaining the remainder has been the inspiration for much of the economic research published after the Great Recession.

And University of Maryland economists Katharine Abraham and Melissa Kearney, in a new paper, have broken out the causes for those missing jobs:

- Imports from China: 2.65 million jobs

- Automation: 1.4 million

- Minimum wage increases: 0.49 million

- Increasing numbers of Social Security Disability recipients: 0.36 million

- Increasing numbers of veteran’s disability recipients: 0.15 million

- Increases in numbers of incarcerated individuals: 0.32 million

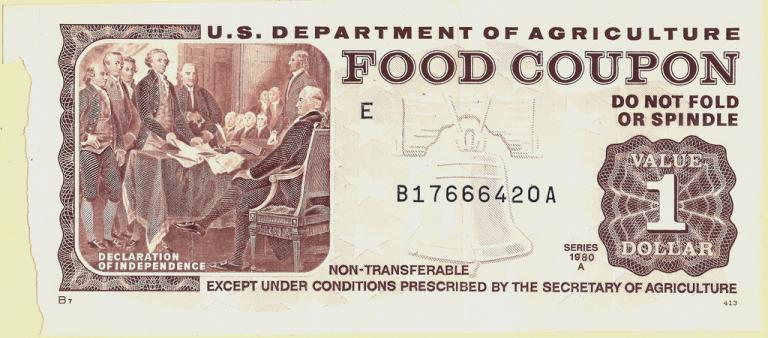

- Immigration (“most research indicates that immigration does not reduce native employment rates”), food stamps, Obamacare impacts, men voluntarily leaving the workforce to be come stay-at-home dads/husbands: no impact

- Decline in job mobility, video games/opioids/changing youth culture: unknown/unquantifiable impact.

So immigration is absolved then, right? I’m not so sure.

In the first place, some of these causes are not like the others. Increased numbers of disability recipients, incarcerated individuals, young adults preferring to live in mom & dad’s basement rather than get a job, are all factors contributing to a reduced labor force. Minimum wage increases speak to the relative desirability of workers to employers of unskilled workers.

But globalization, automation, and immigration are different, and have to do with the number of jobs available. And the conventional wisdom, in all three cases, is that individuals displaced by these causes are able to find work in other fields, in a strong economy, and that the greater prosperity that these developments bring, opens up more jobs elsewhere.

As it happens, the Post reports that they absolved immigration of having any impact on jobs not because of the economists’ own research/modelling, but as a matter of conventional wisdom/prior research. And the actual paper confirms this; they cite one study that finds that each 1% increase in immigration was associated with a 1.2% decrease in wages of less-skilled natives, another that found that in the 20 years from 1980 to 2000, immigration increased the male labor force by 10% and caused a drop of 9% in the wages of high school dropouts, and an overall wage drop of 3%. Other studies, which examine effects on workers split into occupational rather than educational groupings, find smaller negative or even potential positive wage effects (though I’m skeptical that splitting workers by occupation is the right way to go, when workers can move from one occupation to another more easily than they can move to higher education levels). But even the studies showing depressed wages don’t determine a loss in jobs, so they discard immigration as a contributor to declines in jobs.

This contrasts to their analysis of the impacts of offshoring, specifically to China, and automation, where they develop estimates for impacts of these elements and, as my kids would say, “math out” a figure in number of jobs lost. They cite a 2016 study which calculated the effect of trade with China as a reduction in employment of 2.37 million jobs, which they increase by 12% by extending the timeframe to produce 2.65 million jobs lost, and they calculate the effect of robots by multiplying out an estimate of 5.6 displaced workers per robot times 250,475 robots deployed in 2016, to yield 1,402,660 displaced workers.

But it doesn’t seem to me that there’s a bright line between “jobs taken by immigrants” and “jobs lost to robots or the Chinese,” since any job that’s held by a (new) immigrant, or which is created and for which a (new) immigrant is hired, is a job which could have gone to someone displaced in this manner. One might even say that immigration and globalization are two sides of the same coin: it’s just a matter of whether the foreign-born workers willing to do the work for less live overseas or right next door. To be sure, immigrants, living in America, are consumers as well as workers, but their consumption isn’t really comparable to native-born workers, since, at least for significant number of years after their arrival, generally speaking, they consume little here in order to send significant sums of money back home.

In that sense, I’ve always viewed limits on immigration — that is, as opposed to our de facto open immigration system, in which it’s still relatively easy to find forged identification and a job — as a sort of backstop to globalization and automation, by providing or holding open for native-born Americans, jobs which aren’t as easily automated/offshored.

The study seems to assume that all workers have a specific, unalterable occupational field, so that available employment in one occupation doesn’t translate into available jobs for individuals in other occupations. But this is a very limiting assumption. Consider the fact that, when the auto factories in Michigan started to close, enough of those workers moved out-of-state that the phrase “Michigan diaspora” gets 731 google hits. How many of this new generation of former factory workers would have taken up jobs in the poultry processing plants, for instance, had these employers not found a ready workforce in the form of immigrants, often illegal immigrants, willing to accept lower wages and worsened working conditions?

If there is no net impact due to immigration because it’s a fallacy that there are a fixed number of jobs available, then the same ought to be true of automation and offshoring. That the authors conclude otherwise suggests that they didn’t want to counter the prevailing accepted opinion on the matter.

Image: https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2001/08/images/20010826-1.html