In China, people will simply tell you, “You’re fat,” as a way of showing affection. For them, making such comments (including “You’re too skinny”) expresses their concern for your health. Most Americans can’t “hear” the love.

I think something similar goes on in the social media exchanges, as typified by Jonathan Leeman’s recent 9Mark editorial and the flurry of reactions it spurred.

For me, this is a painful post to write. My flesh wants to “pick a side” and spout off angrily at people who seemingly lack any mark of Christian humility and graciousness. But I hope to identify where some miscommunication is happening, then suggest constructive ideas to move us forward.

I write as a longtime (but former) Southern Baptist. But I also endorsed Beth Allison Barr’s book and adamantly care about issues raised by so-called “woke” writers. Therefore, I will attempt to offer a generous reading of the recent 9Marks article, despite my impulse to respond in a contrary manner. Where I reference Leeman, I could just as quickly cite others since so much of what he says aptly represent the concerns of countless conservative evangelicals, both in their confusion and coherency.

I’ll approach the conversation in three parts. First, I’ll begin with where I think Leeman makes legitimate points. Second, I’ll note a few unhelpful bits from his editorial as a way of highlighting how we talk both past and down to others. Third, I’ll sketch a few ideas to make genuine progress.

Digging Deeper to a Core Concern

Leeman raises numerous issues that are hard to sort out. Much of his argument (I think) is unnecessary and distracts from what (I think), in fact, disturbs him and others. Accordingly, 9Marks is justified in their fundamental concern but wrong in framing the problem and thus making their argument.

Why do I say this? Because he eventually affirms much of what he at first seems to dismiss. For example, whereas first appears to object to David Gushee’s comment that “the Bible is always an interpreted text, and that we flawed, limited, self-interested people are the interpreters” Later, however, Leeman concedes,

“We cannot help but speak to what we think is true, even the person who denies that truth exists. To be sure, none of us possesses God’s perspective and in one sense we should always hold our evaluations with a loose grip.”[1]

Upon closer reading, what fundamentally agitates him seems to be this: Much of theology today is being dismissed out of hand as merely “white” and/or “male,” as though such interpretations had no possible link to Scripture and church tradition.

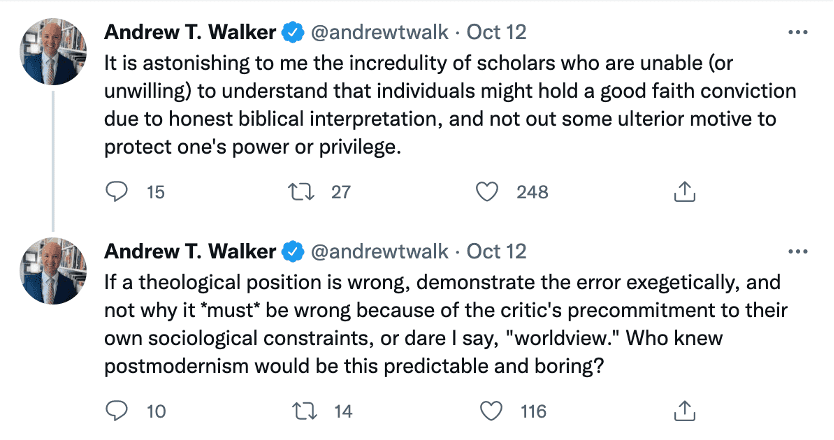

Throughout the article, this theme emerges repeatedly. Leeman’s underlying concern is captured well by Andrew Walker, whom he quotes:

Simply as stated, this is a reasonable concern. Sadly, everything goes utterly haywire when Leeman and others then try to diagnose the problem and offer a prescription. It’s at this point that innuendos, name-calling, and social media “burns” enter and complicate things.

Simply as stated, this is a reasonable concern. Sadly, everything goes utterly haywire when Leeman and others then try to diagnose the problem and offer a prescription. It’s at this point that innuendos, name-calling, and social media “burns” enter and complicate things.

Distraction and Defensiveness Make Us Deaf

We should assume Leeman and others have good intentions. Therefore, based on my decades in conservative Southern churches, I can only suppose Leeman’s less constructive comments stem from frustration and fear.

The following instances serve as a case study in talking past one another. It happens when we don’t attempt to represent other people in ways that they recognize as their positions. We further create frustration and confusion when we don’t give people the benefit of the doubt.

Consequently, the distraction and defensiveness only make us deaf to what others (and perhaps the Holy Spirit) are saying.

1. Tone

Leeman’s tone is counterproductive and unhelpful.[2] He cryptically speaks of “the work of wolves.” His reference, however, is ambiguous. Is he referring to Beth Allison Barr? Kristen Kobes Du Mez? Others?

Elsewhere, Leeman does seem to have Barr, Du Mez, Jemar Tisby, and others squarely in view. He says, “It’s like they’ve taken a hike with the devil and asked him to explain how he interprets all the vistas before them.”

Not. Helpful.

2. Strawman

Leeman’s editorial is chock-full of strawman arguments, which (again) can easily be avoided by laboring to accurately reflect others’ views in ways that they recognize.

Here is one place where Leeman’s counterpoint implicitly creates strawman arguments:

“In short, Christians should read history and learn it. But they must not trust any historian like they trust the Bible. Teach your members that we can learn from the works of history and sociology, but it’s only the Bible which gives us a God’s-eye view of life in the universe.”

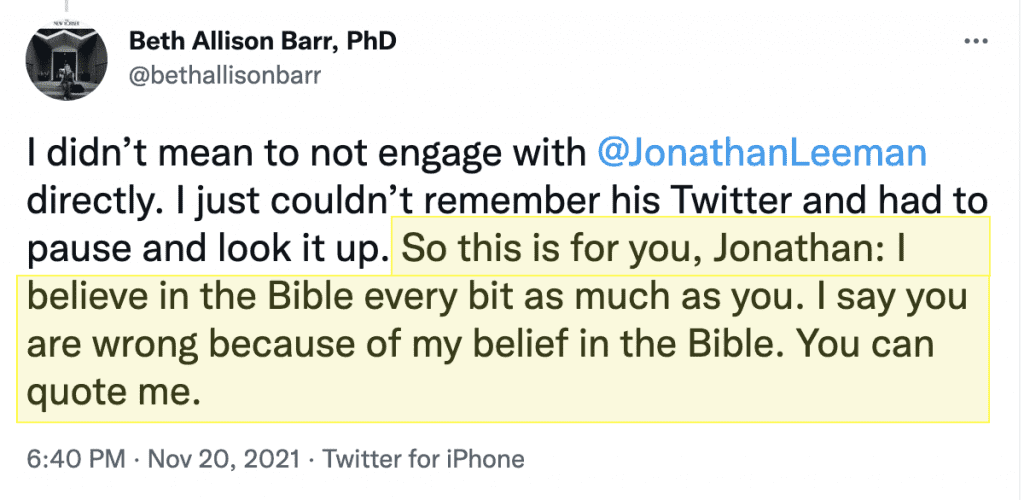

Barr, Du Mez, Tisby agree: Trust the Bible! And, yes, there’s a sense in which the Bible gives a “God’s-eye view of life in the universe.” But Leeman fails to see that none of us have an absolute perspective on absolute truth. Our theology is not entirely equivalent to the Bible. Biblical truth is always bigger and better than our theology.

At best, we all have a relative perspective on absolute truth. Leeman and others seem fearful to take the implications of that fact seriously. In alarm, they needlessly mishear such a statement as if I or others advocated relativism. Absolutely not!

Another of Leeman’s strawmen is his contrast between the Bible and personal stories. He writes, “The answer is to do better exegesis. Our doctrine can fail us, but the answer is not to give final authority to our stories and experiences.” Yes! Yes! And Yes!

While there are certainly people who do think personal stories trump Scripture, that is not the case for those he targets in the article.

While there are certainly people who do think personal stories trump Scripture, that is not the case for those he targets in the article.

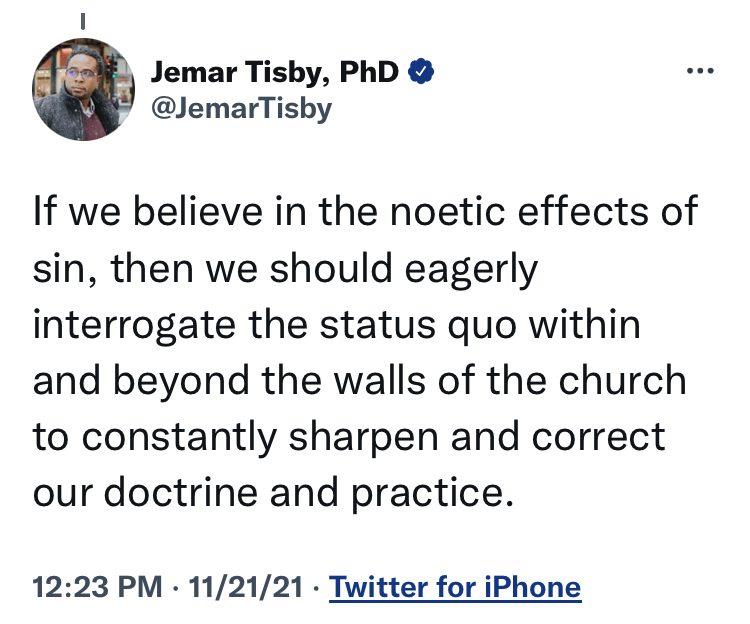

Concerning Tisby, Leeman adds,

“Yet should we assume Tisby’s choice of stories offers a perfect God’s-eye view of white Christians in the past or present?”

Honestly, who assumes that? Not Tisby. That’s an unwarranted charge against either him or his readers.

3. Naïve?

Finally, Leeman’s comments about the scholarship of Du Mez and Tisby are inexplicable, so much so that I’m tempted to call them “disingenuous.” That’s not fair to his character, so the best alternative I can come up with is “naïve.”

He critiques Du Mez’s argument by attacking her historical argument:

“Yet when, for instance, Du Mez argues that post-war white evangelicalism was characterized by patriarchy and toxic masculinity, there’s no text or fixed data set to check her work against. She might offer 14 or even 140 examples to prove her point. Yet how do we know that 140,000 counter examples remain unmentioned? We can learn from those 14 examples— “Don’t do what those guys did!” Yet her overall thesis about what “evangelicals as a whole were like” might simply restate her ideological and theological viewpoint.”

By his logic, no historian or social scientist could ever make truth claims unless their evidence was virtually exhaustive. Given the limitations of space, it’s natural that historians can only demonstrate frequency and patterns of behavior. They don’t claim that to disprove any possible counterexamples.

In short, Leeman’s counter may be naïve, but it’s undoubtedly irresponsible.

The Presence of Irony

One sign that parties are talking past each other and might actually agree (more than they suspect) is the presence of irony.

For example, Leeman says,

If postmodernism, critical theory, and the deconstruction project rightly point to the connection between doctrine and power, they wrongly limit its scope. Or as Kevin DeYoung puts it, “Critical race theory doesn’t go far enough…. The fundamental problem of CRT, DeYoung writes, “is limiting ‘power’ to the one axis of race, class, and sex.

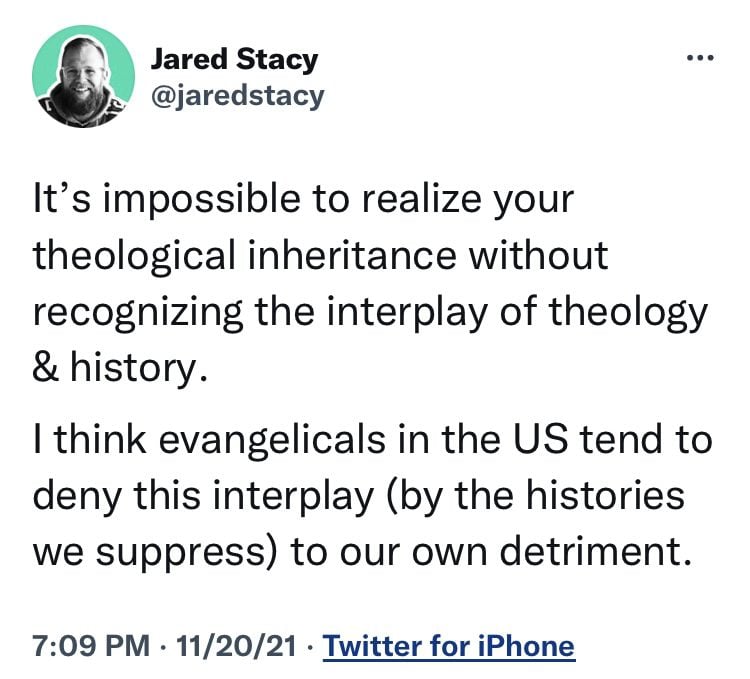

Ironically, evangelicals sympathetic to CRT highlight race precisely because they think American Christians “don’t go far enough” with their understanding of sin (e.g., systemic and historical, not just individual) and of the gospel (including but going further than personal salvation).

Furthermore, Leeman levels criticism against Barr, Du Mez, Tisby, etc. (see Leeman’s point #6), whom he likens to Pharisees, propping up history and tradition above the Bible. Yet, he then contends,

“In this postmodern moment, people’s personal stories and group histories are leveraged to question traditional doctrines. Liberation theologies challenge traditional views of the atonement, eschatology, and even God. People’s experiences of abuse challenge the traditional view of male headship in the home and church.”

But is his lens for interpreting Scripture? He underscores the importance of tradition when it agrees with his interpretation of the Bible.

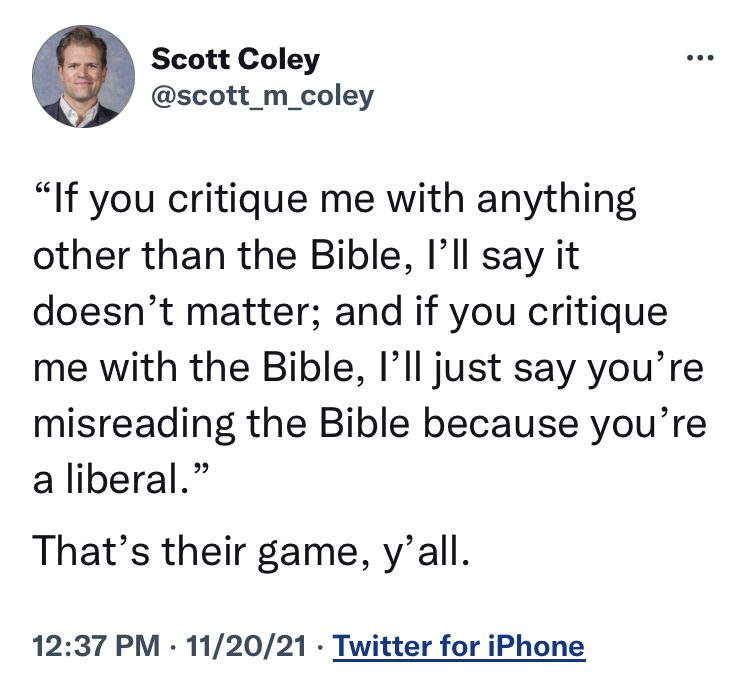

As long as conservative evangelicals argue in these ways, people write them off, in agreement with Scott Coley’s Tweet above.

As long as conservative evangelicals argue in these ways, people write them off, in agreement with Scott Coley’s Tweet above.

Constructive Suggestions

Here are a few ways for all parties to move forward constructively.

1. Meet One Another

First, relevant conversants (re: evangelicalism, race, and gender) could convene a smallish meeting or consultation. Once together, they can *hear* one another, not simply read each other. This would help to correct the tone not only of participants but also of those they influence.

2. Apply Advice

Second, apply much of Leeman’s pastoral advice to theological and scholarly interactions. For example, he urges his opponents to assume innocence before guilt. Leeman writes,

“We treat one another as innocent until proven guilty, insisting on due process before handing out indictments. Folks used to call this giving each other the benefit of the doubt. Apart from due process, we will necessarily remain divided and tribalized.”

Agreed! Shouldn’t this apply to Barr, Du Mez, and others as well? No doubt, this is advice that all sides should heed.

Likewise, Leeman says,

“Most crucially for this conversation, it helps us lower our defenses and listen earnestly to charges of sin made against us and our group. It helps us hear the 10 percent of truth from the angry member.”

Yep. Everything would improve, including our theology.

3. For Leeman’s “opponents”

If people want to make a stronger case that Leeman and others will find persuasive, they need to have criteria to establish when “white privilege” is being used such that “white” arguments could not emerge from a sincere reading of the text. Until then, expect conservatives to react defensively.

4. For Leeman and friends

How might I advise Leeman and others like him?

There is a danger that his article will incline readers to dismiss the concerns of Barr, Du Mez, Tisby, etc., out of hand. So, here’s an idea. I suggest that 9Marks (and similar ministries) take up their concerns with such sincerity and vigor that some might even dare to call 9Marks “woke.” Specifically, they can begin by publicly wrestling with the question, “To what degree does whiteness affect theology and biblical studies?”

These suggestions are neither expensive nor time-intensive, yet they can bring much fruit. They testify to our unity in Christ rather than a unity rooted in political ideologies or national narratives.

[1] Likewise, Leeman states, “Gushee and the deconstruction project are right about everyone’s self-interest.” By “deconstruction,” they don’t refer to the social phenomenon of people who “deconstruct” and leave the church. Put simply, they refer to the task of deconstructing theological paradigms.

[2] I am not saying that others don’t have the same problem. I can only say so many things at one time.