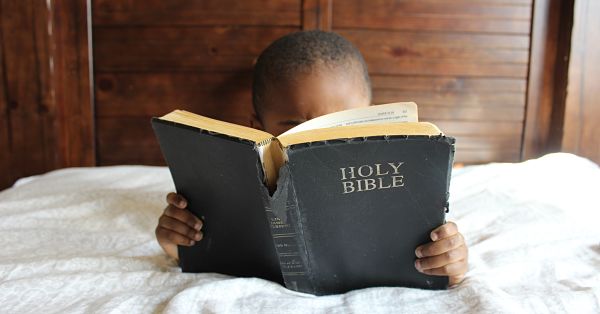

In Defending Shame, Te-li Lai says, “In essence, the goal of Paul’s shaming refutation is Christic formation” (106).

In Defending Shame, Te-li Lai says, “In essence, the goal of Paul’s shaming refutation is Christic formation” (106).

This claim raises several questions concerning the interconnection between honor, shame, and Christian character. This is the third in a 3-part mini-series focusing on that subject. Today, I simply offer a few practical applications stemming from what’s been said. My suggestions will make better sense to those who have read the previous two articles.

1. Methods

We can assess our own attempts to attain honor and avoid shame. This point builds from my first post, where I explained 4 ways that we seek honor and/or avoid shame.

- What do we regard as honorable and shameful?

- Whose opinion matters most to us?

These are questions that need to be discussed openly. Talk about this with others! It’s not shameful to talk about shame! It’s courageous and unspeakably valuable.

How might God/we redeem our shame for the sake of honor (bringing honor to God, others, and ourselves)?

2. Motivations

Reflect on the various motives that animate our lives. (In part two, I highlighted 4 levels of motivation that shape our moral decision-making from an honor-shame perspective.)

- Why do we act as we do? What do we appeal to when trying to motivate others?

- How might we reinforce godly desires so as to plant Christ-honoring values in our hearts?

- What types of identities challenge our identity in Christ?

Again, examining our methods and motivations for seeking honor and avoiding shame is not something to be shy or embarrassed about. It’s simply being honest about what we all do.

What about in the church specifically?

3. Intentionally develop deepening relationships

Honor and shame derive their power from relationships. They only have their meaning and significance within a community.

If we persist in isolating ourselves or if we deny that we really need other people, then we should not be surprised or offended when a drought plagues our church. Isolation and individualism create social droughts that harden hearts and slowly make us uninformed or indifferent to the circumstances of others. When we are famished and starving for meaningful connection with others, there is a scarcity of joy. Hope dries up. The seed of the gospel does not flourish in communities marked by shallow relationships.

(For a deeper, cognitive level explanation, check out Enhancing Christian Life: How Extended Cognition Augments Religious Community).

We cannot embrace American individualism and suddenly think we can use “shame” as a handy tool to fix others’ problems. Te-Li Lau says this about the church:

“Paul envisions the community of faith as the earthly counterpart to the divine court of opinion. Its role is to maintain the plausibility structure that undergirds the gospel worldview, instilling, perpetuating, and reinforcing in each of its members the set of values that are established by God. Thus, believers are to resist making distinctions among themselves based on external social criteria, and they are to honor and imitate those who exemplify the fundamental values of the gospel. In essence, the community must remind itself that the basis of any true honor is Christ” (Defending Shame, 152).

How are you and we intentionally forming this sort of church? Unless you are an elder, don’t ask, “What is their role?” Instead, ask, “What is our role?”

4. Our Use of Shame

When we evaluate and plan our own use of shame, ask, “Are we pushing people away or pulling people in?”

In Misreading Scripture with Individualist Eyes, the authors say this:

“Shame is a tool collectives use to enforce and reinforce their collective values. In the Bible, when one doesn’t embody our values, we can use shame to pull them back, because they are we. It’s an insider tool. But, alas, shame can be misused, to push them away, where they become no longer we. Shame used properly happens before someone moves too far from the values of the group and can center them. As with other social tools, such as honor or guilt, this assumes the values we want to enforce and reinforce are good ones” (189).

They elaborate on the inner rationale that distinguishes a collectivist culture. This sheds light on the thinking that should inform the church’s approach to training and discipline. They write,

“It is not that the community is alarmed that I (as an individual) have moved too far. Their thinking is more alarm that I have pulled all of us off-center. I am part of us, and I am influencing all of us. We could be known as a community that has drifted away from the proper way to treat someone with respect! My community will use shame to make me aware that I have drifted. The goal—and this is critical to understand—is to pull me back toward the center, for everyone’s benefit. We have rescued me and us” (184).

5. Whom do we lift up as role models?

Who are our role models? The people we praise, admire, criticize, and ignore all represent the values that we think worthy of praise or shame. If we generally exalt the eloquence, hard-work, affluence, education, and independent spirit of certain people, we will have a hard time instilling and reinforcing biblical virtues like humility, inter-dependence, generosity, and prayer.

Nothing is wrong with eloquence and hard work; nothing is wrong with education. They are merely tools that reflect God’s grace and are meant to serve greater purposes. Who are the people and virtues that we most talk about and get us most excited? Do we feel more ashamed because we lost our job during the recession or because we hardly spend time with our kids or our brothers and sisters in Christ?

A practical thing we can do is to start hanging out with those people around us who embody or live out the type of virtues we want to foster in ourselves. This is a strategic way to develop the right sense of honor and shame within our hearts and minds.

For a deeper dive into this topic, check out a recent talk I gave at Redemption Tempe.