The Bible not only gives us our message; it should shape our methods. In One Gospel for All Nations, I suggest that the biblical writers have a distinct pattern of presenting the gospel. In effect, they provide us with a firm and flexible model for contextualizing the one gospel in any culture.

I know that sounds like an audacious claim. Yet, what if it’s true? Might we then be able to change the conversation about contextualization from mere principles to actual practice?

Accordingly, the Gospels not only tell us what to contextualize (i.e. the gospel); they demonstrate how God contextualizes the gospel.

A Biblical Pattern of Contextualization

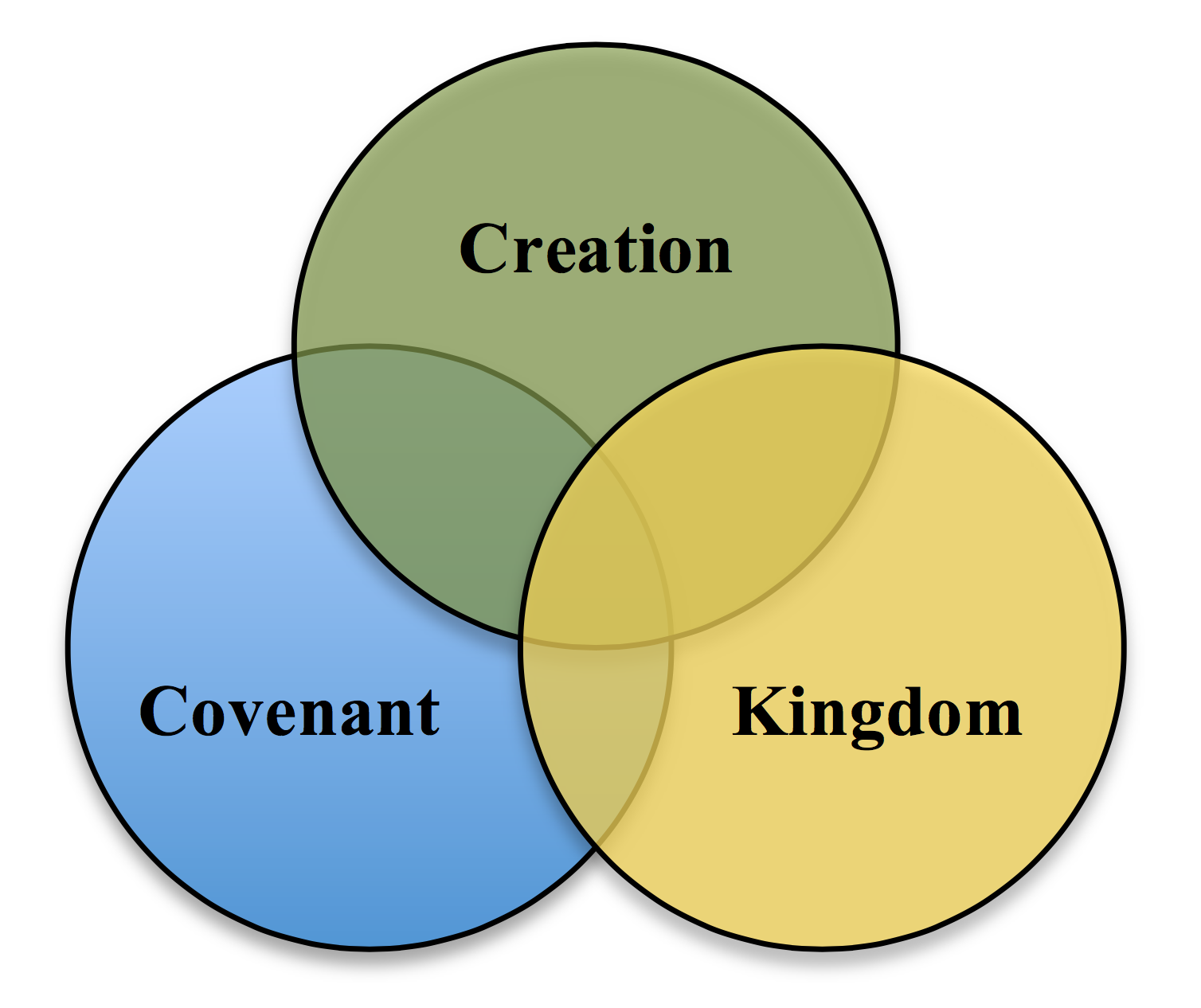

The biblical writers consistently use at least one of 3 major themes to frame their gospel discussions––creation, covenant, and kingdom. Scholars have long identified these motifs within biblical theology; strangely, this fact has little effect on how most people understand and present the gospel (i.e. as a “how to” message”).

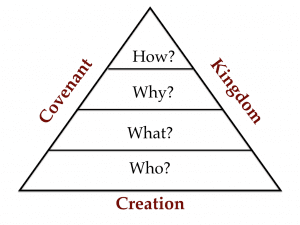

Within these 3 framework themes, we can talk about various other explanatory themes, including important images like justification, redemption, and the atonement. Taken together, these themes explain who Jesus is, what he does, why he matters, thus how one should respond.

Each of the above themes has significance inasmuch as they play a role in the grand biblical Story. In this way, biblically faithful contextualization is firmly rooted in exegesis and biblical theology; yet contextualization can be culturally meaningful because Scripture gives us a flexible model that draws from the entire canon, for the sake of all nations.

The Gospels Contextualize the Gospel

Notice how the Gospel writers employ the above pattern when crafting their accounts. The following is a small sample of many noteworthy observations that could be noted.

1. Framing the Gospel

Famously, the (new) creation theme frames the entire Gospel of John, from “the beginning” (1:1) through the resurrection account (such as where Jesus is presented as the new Adam, a “gardener” (20:15), who rose to life on “the first day of the week” (20:1).

Let’s not forget that Luke first traces Jesus’ genealogy back to “Adam, the son of God” and them immediately places Jesus in the desert where Satan challenges Jesus to prove that he is the “Son of God.”[1]

Matthew frames the life of Jesus as the one who fulfills God’s covenant promises with Abraham and David. In effect, Matthew shows how God uses the story of Israel to contextualize the person and work of Jesus. In death, Jesus offers the “blood of the covenant” (Matt 26:28; Mark 14:24; cf. Luke 22:20). In Luke 1:72, the birth of John is interpreted as God’s “remembering his covenant, the oath that he swore to our father Abraham.”

Matthew frames the life of Jesus as the one who fulfills God’s covenant promises with Abraham and David. In effect, Matthew shows how God uses the story of Israel to contextualize the person and work of Jesus. In death, Jesus offers the “blood of the covenant” (Matt 26:28; Mark 14:24; cf. Luke 22:20). In Luke 1:72, the birth of John is interpreted as God’s “remembering his covenant, the oath that he swore to our father Abraham.”

The Gospel writers indisputably represent Jesus as a king whose ministry ushers in a new sort of kingdom. They repeatedly stress the fact that Jesus is the “Son of David,” “the Christ,” and thus, as Nathanael confesses, “the Son of God . . . the King of Israel” (John 1:49).

In Michael Bird’s excellent book Jesus is the Christ, his central argument is that “the messianic identity of Jesus is the earliest and most basic claim of early Christology” (p. 4). As Bird explains, this is a distinct royal vocation. In the various trial accounts, Jesus is ultimately convicted and killed for claiming to be Israel’s king.

2. Explaining the Gospel

The big question of each Gospel is simply, “Who is Jesus?” John is most direct when he says, “these are written so that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God” (20:31). With those in Jerusalem, so we are supposed to ask, “Who is this?” (Matt 21:20). Moreover, Hays concludes, “It is precisely through drawing on OT images that all four Gospel portray the identity of Jesus as mysteriously fused with the identity of God.”[2]

Who Jesus is…is known by what Jesus does. Thus John 10: 24–25 says,

“the Jews gathered around him and said to him, ‘How long will you keep us in suspense? If you are the Christ, tell us plainly.’ Jesus answered them, ‘I told you, and you do not believe. The works that I do in my Father’s name bear witness about me’’’ (cf. John 9:32–33; Mark 1:34).

His teachings, healings, miracles and symbolic protest in the Temple all signify to his identity.

It is only when after answering the above questions that readers discern why Jesus is important. John states “by believing you may have life in his name” (20:31); through Christ there is resurrection for all who believe (11:24–25). Matthew even adds, “you shall call his name Jesus, or he will save his people from their sins’” (Matt 1:21). This is because Jesus has authority to forgive sin (Matt 9:6; Mar 2:10; Luke 5:24).

It is only when after answering the above questions that readers discern why Jesus is important. John states “by believing you may have life in his name” (20:31); through Christ there is resurrection for all who believe (11:24–25). Matthew even adds, “you shall call his name Jesus, or he will save his people from their sins’” (Matt 1:21). This is because Jesus has authority to forgive sin (Matt 9:6; Mar 2:10; Luke 5:24).

How should people respond to this gospel? Mark succinctly summarizes Jesus’ message, “ . . . the kingdom of God is at hand; repent and believe in the gospel” (Mark 1:15; Matt 3:2). He calls people to become disciples by following him (Matt 4:19; Luke 18:22).

Contextualization according to the Gospels

As Scot rightly summarizes, the early Christians “called these books ‘the Gospels’ because they are the gospel.”[3] Although many people think of Acts 17 when they hear “contextualization,” we should think of the four Gospels!

Biblical scholars cannot only help us interpret the Bible; they can help us learn to contextualize it. This is one reason I wrote One Gospel for All Nations. We desperately need to bring biblical theology and missiology together.

What do you think?

[1] Hays, Reading Backwards, Kindle loc 2418.

[2] Richard Hays, Reading Backwards. IVP, Kindle loc 2897

[3] Scot McKnight, The King Jesus Gospel, 80.