Among Joachim of Fiore’s many remarkable ideas, his unique understanding of the Antichrist has, from his own times until now, never failed to excite interest. This can be succinctly demonstrated by the fact that, on the day my previous article on Joachim went live, I happened across a slideshow article from the website Stars Insider entitled “What do we know about the Antichrist?” Joachim is featured prominently but his world-transforming idea of the Three Ages goes completely unmentioned. Rather, it is his claim that there are multiple Antichrists through history that receives all the attention. It seems that, even in our supposedly rational age, it is Joachim’s speculations on the Antichrist that are doing much of the work to keep his name alive.

In a way, this is fitting. For the same was true during Joachim’s own lifetime. Marjorie Reeves, in The Influence of Prophecy in the Later Middle Ages, states that Joachim was primarily regarded amongst his contemporaries as an authority on the Antichrist. She remarks that, as late as 1250—nearly five decades after the abbot’s death— “Joachim was not yet known for the doctrine of the three status, but still as the prophet of Antichrist” (Reeves 185). Indeed, during Joachim’s famous meeting with King Richard the Lionheart at Messina in late 1190 or early 1191, the nature and identity of the Antichrist was the main topic of the two men’s conversation. As much as the Three Ages came to define Joachim’s legacy and reputation over the long arc of history, his claims about the Antichrist have always been critical to his public reception.

What, then, did Joachim actually believe about the Antichrist? The Stars Insider article is right about his general viewpoint: Joachim did believe in multiple Antichrists. More than that, he believed in a sequential list of Antichrists, each appearing at a different moment in history. As Joachim saw it, every age produces its own Antichrist. This was, by itself, a complete departure from all previous end-times thinking in Christianity. But even that does not entirely do Joachim justice. His thought was far more complex, and his influence on future beliefs surrounding the Antichrist more extensive, than any brief summation of his ideas can properly convey.

For one thing, Joachim based his new conception of the Antichrist upon the Book of Revelation. This, on its own, does not seem all that extraordinary. After all, in more recent times, Christians and non-Christians alike take it for granted that Revelation is the Christian version of the end of the world story. For believers in particular, it is usually regarded as a complete, comprehensive, and definitive guide to the end-times and their unfolding. Today there is a whole cottage industry dedicated to studying Revelation and mapping its gnomic descriptions onto current events. The general figure of the Antichrist is inseparable from the description of him provided by the Book of Revelation.

But this was not always the case. During the early centuries of Christianity, Revelation was just one of several accounts of the end which captured the minds of believers. Even amongst the soon-to-be canonical texts, Christians had a large assortment of visions of the end to draw from. There were, of course, the prophecies of Christ and the scattered remarks of the apostles about things to come. But there was also the rich apocalyptic tradition of the Old Testament. There could be found both Ezekiel’s vision of the New Jerusalem and Daniel’s prophecy of the Four Empires, and their influence on Christian eschatology would be immense. Even when Revelation was safely ensconced in the canon, included in the Bible as its very last book, this did not elevate its status above other end-times accounts. Instead, the opposite happened, and Revelation fell into a long period of near-obscurity as Christians ignored its confusing happenings and mysterious imagery in favor of more straightforward accounts of the end.

We have seen in previous entries that, for the medieval mind, a number of other texts filled the place that Revelation does today. While perhaps no one text of the time was wholly “definitive,” the closest thing to a standard account of the end was not the Apocalypse of St. John but that of St. Methodius. The Pseudo-Methodius may not even be included in most collections of apocrypha today but, at the time, its influence was undeniable. Its story of a heroic Roman Empire, personified in a messianic Last Emperor, menaced in the east by the demonic forces of Gog, Magog, and Antichrist had far more currency in the medieval world than Revelation’s own apocalyptic narrative, thanks in large part to a legion of texts like the Sybilline Oracles that took up and expanded upon the Last Emperor idea. As far as the Antichrist himself went, his generally accepted biography came from Adso of Montier-en-Der, who claimed in his Letter on the Origin and Time of the Antichrist that the Antichrist would be a Jewish man who would claim the role of the Davidic messiah and incite the Jewish people against the Christians. This deeply antisemitic image of the Antichrist became standard in the Middle Ages, despite being entirely absent from Revelation itself.

This was a general theme with medieval apocalyptic texts. They gladly turned Revelation on its head at almost every opportunity. Whereas St. John’s Apocalypse had presented an eastern church, still not entirely disconnected from its Jewish roots, under threat from a Roman Antichrist, the medieval texts portrayed a heroic Roman Empire attempting to fend off the eastern—and often Jewish—threat of the Antichrist. This vision of the end was still very much dominant in the twelfth century and accepted in some form by nearly everyone. Thus, it would have been no surprise if a learned individual of the time drew upon it when formulating his own ideas.

But Joachim did not do this. Instead, he turned back to Revelation, making it the bedrock upon which he built his new eschatological system. Joachim thereby saved Revelation from the neglect and obscurity into which it had fallen. It was the popularity of his own system and the extensive use it made of Revelation that solidified Revelation as the go-to book for information on the end-times. Before him, the generally accepted apocalyptic narrative may have shared a common stock of characters and events with Revelation but did not draw very much on Revelation itself. After Joachim, Revelation became the chief source for the Christian story of the end, the one narrative that all others had to abide by. Joachim lived far too late to play any role in its canonization or placement at the end of the Bible, but the whole modern notion that Revelation is the Christian account of the last days—with all that that entails—is due to him. Even among scholars who understand the scope of his influence, he still does not get enough credit for that feat.

Joachim’s choice to return to Revelation and ignore the popular narrative reveals much about his own character. It speaks to how he valued the Bible as the chief source of spiritual knowledge, something not true of everyone even in a time far more Christian than our own. Furthermore, it demonstrates his commitment to finding meaning and significance in the whole Bible and not just the popular bits. It might not match up with the popular image of him as an eccentric mystic replacing the Bible with his own personal revelation, but Joachim’s method was resolutely “Bible-based.” Indeed, this is another aspect of Joachim that looks surprisingly modern, even as he remains unflinchingly medieval. Like a modern scholar, he deliberately chose to cut out the noise of received opinion and return to the primary sources. For him, those primary sources were the books of the Bible, and he drew his conclusions by reading them closely and taking into consideration what previous theologians had said about them. Given his methodical way of proceeding and his dedication to the Bible as a primary source, there was no way he could avoided a deep dive into Revelation if he wanted to come to any firm conclusion about the end of all things.

That being said, one suspects he did not come to Revelation with a reluctant heart. There was something about him which made embracing it easier than it would be for nearly anyone else. For most people, Revelation is quite off-putting for the first several—or first several hundred—readings, filled to the brim with dramatic imagery, bizarre and brutal, the type of things that can be felt viscerally but never truly understood. The action unfolds frantically and at breakneck speed. The shifts between Heaven and earth are so rapid that it is easy to forget where one is at any given moment. John makes very few attempts to hold our hand or guide us through what we are seeing. This book shows so much and explains so little. For the average person, reading it is a process of constant and prolonged disorientation.

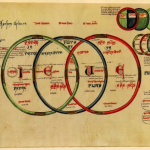

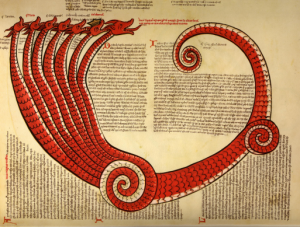

Joachim was not the average person. Indeed, there has probably never been an individual more at home in the dizzying world of Revelation than he was. Despite being a prolific author, Joachim was never quite at home in the written word. His books abound with charts, figures, and diagrams, awkwardly breaking up and breaking into the written text. One of his most famous books, the Liber Figurarum, consists entirely of drawings and images, and even later legends and forgeries would draw upon his reputation as a pictorial prophet. His prose in general is dense, difficult, and labored, but he never misses with a striking image. In short, Joachim seemed to think more in images than in words and this put him in rare sympathy with the author of Revelation. Revelation aligned with his own natural ways of thinking; Joachim responded so fully to St. John’s panoply of disturbing, exciting images because they reflected how he himself thought, meditated, and experienced the world.

The book was also far more closely aligned to his own personal views and inclinations than the popular apocalyptic narrative was. Joachim was always suspicious of political power and the way it tends to corrupt everything. Despite being sought out and patronized by kings and queens, Joachim disliked the political order they represented, perhaps even hoping for its disappearance in the Third Age. He was particularly distrustful of the Holy Roman Empire—still regarded in his time as the continuation of the original Roman Empire—and thus had no interest in portraying a heroic Last Emperor, even if he would ultimately adapt the idea into the more spiritually appealing figure of the Angelic Pope. In this, he found himself in agreement with St. John, who depicted the Roman Empire as “Babylon,” the great evil of the end-times. Meanwhile. the antisemitic trope of the Jewish Antichrist was completely against Joachim’s sensibilities. As noted in the previous entry, Joachim had a much more favorable opinion toward Judaism than just about anyone else in the Christian West at the time. While he still regarded Christianity as the true religion, this did not keep him from maintaining Jewish contacts or being receptive to Jewish wisdom. The abhorrent demonization of the Jewish people inherent in the previous portrayal of the Antichrist was something which he could never abide.

This, indeed, is another one of Joachim’s important contributions to the later development of the Christian end-times narrative in general and the story of the Antichrist in particular. Before Joachim, it was largely taken for granted that the Antichrist would be Jewish. This is rarely the case today, as most modern interpretations forgo this blatant form of antisemitism. Indeed, the current trend in mapping the apocalyptic narrative onto contemporary events is to portray the Antichrist as just as much an enemy of Judaism as he is of Christianity. Joachim was the difference-maker here. He offered the first major challenge to the notion of the Jewish Antichrist. The various Antichrists in his list of seven were a mixture of eastern and western figures but none of them were Jewish. What was more, he was resolute that the greatest Antichrist, the one most other people would consider to be the Antichrist, would be a Westerner and a Christian.

In his tract De Septem Sigillis (On the Seven Seals), Joachim offered a stark warning to his fellow believers, announcing that, in Revelation, “Babylon will also be struck down, which is to say the people who are called Christians but are not” (De Sept. Sig. 244). Joachim was clear, the Babylon of the Apocalypse, the empire of the Antichrist, would not be Jewish, Muslim, or any other sort of outsider. Instead, Antichrist and his followers would all be hypocritical Christians who professed Jesus’s teaching but refused to live their lives according to them. His message to his fellow Christians was clear: do not blame other religions and peoples for the rise of the Antichrist, for the worst Antichrist will come from the ranks of Christianity itself.

Richard the Lionheart found out as much when he went to Messina, ready to launch a crusade into lands that he believed would someday house the Antichrist. He asked Joachim about his prospects of victory and walked away with the abbot’s warning that “The Antichrist has already been born in the city of Rome” (Reeves 7). What Joachim meant by this statement has never been fully deciphered. Marjorie Reeves argues that he expected the Antichrist to be a Holy Roman Emperor, and that he was using “Rome” to mean the empire as a whole. Others, beginning with a dispirited Richard himself, have tended to think that Joachim meant a future pope, giving birth to the trope of the Papal Antichrist that the Protestants would embrace with such gusto in a few hundred years. From Joachim’s own writings, it appears that he expected both a false pope and a tyrannical future emperor; perhaps he thought the next Antichrist would take on both these roles. Regardless, what is clear is that he saw the last Antichrist as coming not from the outskirts, not from the non-Christian east or the Jewish people, but from within the highest echelon of Europe’s Christian ruling class itself.

Joachim thus found himself in complete agreement with St. John in his assessment of the Roman state (whether imperial or papal) as the engine of the Antichrist’s rise. Against the popular notion of a heroic Roman Empire fighting an othered Antichrist, he restored St. John’s original vision of the Roman Empire itself as Antichrist. If that was all he did, he would still have played a major role in the future development of Christian apocalyptic thought. But, as noted above, what really seems to attract interest to Joachim is his view that there had been Antichrists throughout human history. How did Joachim happen upon this unique and peculiar idea, apparently without precedent in Revelation itself? The surprising is answer is that, while it may at first seem at variance with St. John, Joachim came upon this understanding of the Antichrist through his usual method of studying Revelation, and the Bible as a whole, quite closely.

As a devoted reader of Revelation, Joachim could not help but be struck by the “great, fiery red dragon with seven heads and ten horns” (Rev. 12:3). In the next chapter after the dragon’s appearance, another, similar-looking creature appears, “a beast rising out of the sea. It had ten horns and seven heads; on the horns were ten diadems, and on each head was a blasphemous name” (Rev. 13:1). Despite being almost identical in description, these are generally understood to be separate figures; the dragon is Satan and the beast is the Antichrist. Joachim, however, understood them as interconnected; while the dragon represented the devil, it can also be identified with the beast that appears immediately afterward, and thus with the Antichrist. As a result, the seven-headed dragon took on a much greater importance for Joachim than it had for any previous exegete. It was by contemplating this image that he came to his radical conclusion. If the dragon and the beast had seven heads, he thought, each head must represent a different individual. There must not be one, but seven Antichrists.

It is important to emphasize how much of an innovation this truly was. Many contemporary interpretations and commentaries on Revelation accept the idea that the seven heads and ten crowns represent co-workers of the Antichrist, lieutenants who help to carry out his reign of terror. But this was not what Joachim meant at all. He raised all the seven to an equal status as Antichrist—though he accepted that the one commonly called the Antichrist would be far worse that the other six. But what was more, the first six would not be co-workers or lieutenants of the seventh. They had all existed or would exist independent of him, fully being Antichrists in their own right. This was because Joachim saw the seven heads not as a collection of aligned ne’er-do-wells but as a chronological sequence. Each of the seven would be fully Antichrist because each would be the only Antichrist during their own separate period of time. The Antichrist was now not simply the final boss waiting for the faithful at the end of the world’s story. The entire lifetime of the Church was filled with Antichrists, and Christian history was a recurrent struggle against different versions of this ultimate foe.

This type of claim had never been advanced before. It is true that the First Letter of John had warned, “many antichrists have already appeared” (1 John 2:18) but those many, little antichrists were generally accepted to be of a completely different kind and scale than the one great Antichrist that was to come. As Robert E. Lerner puts it in “Antichrist and Antichrists in Joachim of Fiore,” “the ‘many antichrists’ were any members of the diabolically inspired human society of evil, all of whom helped to prepare the way for the true Antichrist’s coming but none of whom were to be confused with this one true Antichrist himself” (Lerner 554). The Middle Ages’ previous leading authority on the Antichrist, Adso of Montier-en-Der came a little closer to Joachim’s main idea when, in his famous letter, he briefly toyed with the idea that “[t]his Antichrist will therefore have many ministers of his malignity, from which many have now preceded [him] in the world, ones such as Antiochus, Nero, Domitian” (Adso 107). But even as Adso seemed almost to glimpse the possibility of many Antichrist-like figures appearing throughout history, he pulled himself back. Figures like Antiochus and Nero would only be servants and “ministers” to the true Antichrist, preparing the way for his coming but still being of a wholly different and lesser caliber that their master.

As Lerner succinctly puts it, “before Joachim medieval Christian theology and folklore allowed the existence of many ‘antichrists’ but only one Antichrist” (“Antichrist” 554). Thus, when Joachim announced that figures such as Nero were not simply “ministers” of a future Antichrist but were full-fledged versions of Antichrist themselves, it marked an entirely new development in Christian eschatology. Augustine had judged all of time between the death of the apostles and the distant, unknowable end as inconsequential to God’s cosmic plan. Joachim restored the cosmic, even apocalyptic significance of historical time. Now every era had its own importance; each one represented another pivotal stage in the battle against Satan and Antichrist. This further emphasized one of Joachim’s most dearly held beliefs: for him, Revelation was not simply a guidebook to the coming end of the world but a written encapsulation of the entirety of human history, past, present, and future.

This all aligns with the most characteristic and original feature of Joachim’s thought in general, namely, his belief that history was a process of development and progression rather than a mere succession of events, which inspired his conviction that all historical time was filled with a higher meaning and purpose. His interpretation of the Bible as a chronicle of ongoing historical processes working themselves out across all of time would naturally work its way into his reading of Revelation. Given how Joachim thought about history and historical development, it made sense for him to see the Antichrist not as a single figure, but as an ongoing process like all the others he had traced from the beginning of biblical time.

Still, he was also doing something else with his Antichrist theory. There is a specific reason that Joachim sets the number of Antichrists at seven beyond the simple fact that both the dragon and the beast have seven heads. For the Antichrist also figures into Joachim’s ongoing effort to harmonize his radical insights with the ideas promulgated by the established Church. Joachim’s system of the Three Ages of history stood in contradistinction to what was then the dominant way of conceptualizing historical time, Augustine’s model of the Seven Ages of the World. The notion that the world’s history could be divided into seven periods in turn inspired the Seven Ages of the Church, which applied the same models specifically to the lifetime of Christianity. Joachim felt it was very important to demonstrate that his new conception of time did not invalidate these previous—and universally accepted—ones. Proving the point was one of his top priorities; he wrote entire works such as De Ultimis Tribulationibus (On the Final Tribulations) and De Septem Sigillis (On the Seven Seals) to fit the seven ages into his tripartite system.

The seven Antichrists allowed him to do just that, at least as far as the seven ages of the church were concerned. Each Antichrist could be mapped to one of the seven eras—which Joachim also equated to the seven seals of Revelation 5-8—and made to represent the chief persecutor of Christians in that time. The traditional structure could be respected while Joachim would still get to portray the Antichrist as another example of the processes of historical repetition and continual development that undergirded his new Three Ages system. Even so, however, there is something unwieldly about it all. Capping the number of Antichrists at seven locked Joachim into a time structure that his thought was already moving beyond. As Lerner reminds us in his earlier article, “Refreshment of the Saints,” “his theory of the three ‘statuses’ was a really new conception of historical advance” (“Refreshment” 118); Joachim’s historical consciousness was too expansive for the simpler model posited by Augustine and his successors to truly satisfy him. He kept bumping up against its limits. In De Septem Sigillis, he has to double the number of ages to fourteen (seven Jewish and seven Christian) to make the old model fit into his more comprehensive view of human history. And in De Ultimis Tribulationibus, he wrestles with Augustine’s claim that the sixth and seventh ages would run concurrently—leaving no time for an earthly Millennium—in order to reestablish the distinctness of the final era and open up space for his Age of the Holy Spirit. The modifications Joachim had to make in order to create a veneer of agreement between his model of history and Augustine’s were definitely ingenious. But their very ingenuity reveals how truly incompatible the seven ages notion—whether of the world or the church—was with Joachim’s new system and how his efforts to make the two cohere only caused him headache after headache.

His treatment of the seven Antichrists also displays his need to go past the limits imposed on him by the seven-ages model. For, in truth, there are not seven Antichrists in Joachim’s system. There are eight. After the seventh, supposedly “final” Antichrist, who will appear in the transitional period between the Second and Third Status, Joachim tacks on one more that will launch the true final assault upon the faithful at the end of the Third Age. He found his warrant for this, once again, in the Book of Revelation. As a close and careful reader of St. John’s words, Joachim noticed something that generations of Christians before him had missed. Revelation 19 sees the beast defeated by Christ at Armageddon. Christians tended to assume (and generally still do), that this is the final battle between God and Satan, good and evil. It is not. After the beast and the false prophet are thrown into the lake of fire, Christ establishes his thousand-year reign on earth. Then, in Revelation 20, we are told:

When the thousand years are ended, Satan will be let loose from his prison, and he will come out to seduce the nations in the four quarters of the earth. He will muster them for war, the hosts of Gog and Magog, countless as the sands of the sea. They marched over the breadth of the land and laid siege to the camp of God’s people and the city that he loves. But fire came down on them from heaven and consumed them. (Rev. 20:7-9)

It is Gog and Magog’s assault on Jerusalem, rather than the beast’s defeat at Armageddon, that marks the true final battle between God and Satan and the true triumph of good over evil. This intriguing fact escaped the notice of Christians for many centuries. But it did not escape Joachim’s watchful eye.

Now, to be fair to medieval Christians as a whole, Gog and Magog had always been an important part of the end-times narrative, even in those eras when Revelation itself was not. Indeed, their mythology was expanded considerably from the scant notices about them in Ezekiel and Revelation. In the folklore of the end, they became two barbaric and cannibalistic nations, trapped by Alexander the Great behind a massive iron gate far to the north. Christians commonly held that, at the end of time, Gog and Magog would finally break through the gate and launch their terrible assault on the world.

There was only one problem. Revelation puts Gog and Magog’s invasion after the death of the Antichrist. But later apocalyptic writers invariably had Gog and Magog attacking Christendom before the Antichrist appeared. In the Pseudo-Methodius and its many descendants, Gog and Magog are adversaries of the Last World Emperor before the coming of Antichrist, and their destruction marks the high point of his glorious reign. The final battle is inevitably the one between Christ and Antichrist—usually on the Mount of Olives rather than at Megiddo—after the Emperor, Gog, and Magog have all left the stage. These writers inevitably either agreed with Augustine and did not include the Millennium in their accounts or repeated the claim of St. Jerome that the millennial era would last for the laughably small period of forty-five days. This meant that the defeat of the Antichrist, and not the thousand-year rule or the battle with Gog and Magog, is the concluding act of history, after which the new heaven and the new earth are immediately ushered in.

This remained the state of affairs until Joachim came along. He restored Revelation’s proper sequence of events, with Gog and Magog coming after the Antichrist. But he also went further. Revelation is ambiguous about who or what the “hosts of Gog and Magog” are. As noted above, Christians almost universally interpreted them as two nations or confederations of nations. Both were seen as comprising whole groups and tribes of people. But this is where Joachim’s dedicated focus to the entirety of the Bible paid off. He had a far greater appreciation for the minutia of the Old Testament than have most other Christians before or since. Because of this, he was able to recognize that the original account of Gog and Magog’s apocalyptic campaign comes not from Revelation but from Ezekiel. There, Gog is not a nation but a single individual, the “prince of Rosh, Meschech, and Tubal” (Ezek. 39:1) who leads the coalition of Israel’s enemies against the chosen people, and Magog is his kingdom.

This led Joachim to a realization. If Gog is a person and not a people, and he is the leader of the final attack on Christianity, then that makes him just like the seven Antichrists who came before him. If this is so, then, as Joachim puts it in De Ultimis Tribulationibus, “either Gog will be the Antichrist or like a great emperor seduced by the Devil” (De Ult. Trib. 187). In other words, Gog is either an Antichrist directly in name or, if not in name, then at least in function. This means that there are eight total Antichrists. Certainly, this made sense of the sequence of events in Revelation, but it created another problem for Joachim. The dragon only had seven heads; there was no room for Gog. But Revelation 12 suggested a solution. That passage says of the dragon, “with his tail he swept down a third of the stars in the sky and hurled them to the earth” (Rev. 12:4). The dragon’s tail become quite important here, perhaps as important as his seven heads are. This gave Joachim an idea. As Lerner says, “Yet even with the ‘great Antichrist’ all the worst oppressors of the faith were not yet counted, for there still remained the tail of the red dragon. Obviously then, the tail had to be Gog,” (“Antichrist” 564). If Gog was the tail of the dragon, it allowed him to be part of the same historical process without forcing Joachim to undo the careful calibration between the seven heads of the dragon and the seven ages of the church, allowing him to paper over the tensions between his own system and the seven-ages scheme he had inherited from his church.

Besides, it gave a certain logic to Gog’s appearance after the thousand years of Christ’s reign in Revelation. If Gog is the tail of the dragon and not one of the heads, it should take a while for him to arrive after the last head has passed by. Joachim could now also keep calling the seventh head of the dragon, the one most people would consider to be the Antichrist, “the final Antichrist” (as he does in De Ult Trib. 182) while allowing Gog to also be an Antichrist after him. In fact, Gog’s position as the tail allows Joachim to keep his exact role and position rather ambiguous. As seen in the statement about the “great emperor” above, Gog was at once an Antichrist, part of the same historical process of persecution of the Church, and yet also not an Antichrist, or at least an Antichrist sufficiently different from the ones that had come before. He got to be distinctive and special without taking anything away from the distinctiveness of the Antichrist represented by the seventh head of the dragon. That Antichrist’s persecution still felt like a climax in history, even as Gog’s own provided history’s definitive end. By walking this careful tightrope, Joachim was able to make one of Revelation’s greatest conundrums into a strength of his own theory while further emphasizing the importance of both repetition and transformation in the unfolding of history.

With his treatment of Gog and the seven other Antichrists, as Lerner puts it, “the abbot effected the first major departure in medieval Antichrist thinking since the days of the Fathers” (“Antichrist” 560). His new theory of the Antichrist had much to recommend it. It found a satisfactory place for Gog and Magog in the end-times scheme while still being loyal to the text of Revelation, making sense at last of St. John’s claim that they, and not the beast, would be the final opponent of God and Christ. It also allowed Joachim to solve some other problems within the text of the holy book. Given his attention to textual details, Joachim could not miss the fact that Revelation identifies the Antichrist with Emperor Nero, whose ciphered name is hidden in the number of the beast. But unlike previous theologians for whom the identification of Christianity’s great future foes with a long dead emperor caused some embarrassment, Joachim had a ready answer. Revelation says that Nero is the Antichrist because Nero had been the Antichrist. Specifically, he was the second Antichrist, the second head of the dragon. But since he was not the only Antichrist, more Antichrists could come along in the future to fulfill the eschatological program. The difficulty could now be sidestepped, with Joachim’s notion of multiple Antichrists once again resolving a significant problem in Revelation and setting the Antichrist idea itself on firmer footing.

Despite these successes, Joachim’s system still suffered from the tensions created by his efforts to bridge the divide between it and the previous conceptions of time. The fact that Joachim had had to make special provision for Gog to keep him from breaking the scheme only demonstrates how poor of a fit the seven ages were for Joachim’s view of history. The truth was that Joachim’s ideas were so expansive that not even eight Antichrists were enough for him. After all, by linking them to the seven ages of the church, he had to limit the existence of Antichrists to the Christian era. But Joachim thought of the processes of history as unfolding across the full scope of cosmic time, from the world’s beginning to its end. Thus, he could not simply confine the process by which Antichrists were produced to the Christian era alone. These same type of figures had to exist in the long period of time before the Incarnation as well.

Of course, given that they lived before the birth of Christ, none of these individuals could be properly called “Antichrists.” But they still represented the same process and the same recuring type of historical figure. For however much he expected the Three Ages to differ from one another, Joachim saw the first two as strikingly alike in some ways. A cursory glance at Joachim’s discussions of history reveals that he thought of it as consisting largely of struggle and strife between the faithful and their oppressors; in De Ultimis Tribulationibus he speaks of how Satan “is known to have waged three great and seemingly general wars under the Old Testament and is shown to wage just as many in the New” (De Ult. Trib. 175). The Third Status would bring relief from this incessant warfare, but the conflict between God and Satan would still determine the course of history until that time. As such, the persecutions and trials endured faithful Christians in the time after Christ had to be seen as part of the same struggle as the trials and persecutions suffered by the Jewish people before Christ’s birth. They were simply parts of the same overarching historical process.

If the process was the same, then it must also produce the same type of figures. There must be persecutors of the faithful in the times before Christ that correspond to the Antichrists who come after. When he combed the Old Testament, Joachim found no shortage of these. There was the Pharaoh who had been the adversary of Moses, Jeroboam who had forever divided the kingdom of David by declaring himself ruler of the north, the Pharaoh Necho and Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon. And then there was the final Antichrist-like figure of the Old Testament era: the Seleucid king Antiochus, who had warred with the Maccabees for control of the Holy Land. With Antiochus, Joachim would make it clear that he thought of the Old Testament persecutors as Antichrists in all but name. He treats Antiochus’s persecution as greater than any other save for those of the seventh head of the dragon and Gog, even saying that the “greatest tribulation … in the days of Gog” will be “similar indeed to that which was done under Antiochus” (De Sept. Sig. 246). For Joachim, Gog and Antiochus were especially similar, such that Gog could even be regarded as a second Antiochus repeated the crimes of the first.

This puts Gog and Antiochus in an interesting positive relative to each other and the seven Antichrists. They bookend the appearances of the seven heads of the dragon, neither of them one of the seven proper Antichrists in the seven-ages scheme. And yet, they are both truly Antichrists, distinct from the seven but still more than worthy of the title for the suffering they cause the faithful. Indeed, in Joachim’s mind, Gog and Antiochus excel most of the heads of the dragon for cruelty and bloodshed, only being matched by the seventh. It was this understanding that finally allowed Joachim to break free of the seven-ages model of history, for the pattern of seven Antichrists can now be subsumed by a pattern of the three Antichrists who appear at the end of each of the Three Ages. As Lerner says, “if salvational history were taken by threes, then three dreadful tyrants were to be counted — Antiochus, the canonical Antichrist (at this point called by Joachim the ‘seventh king’), and Gog — each one coming at the end of a salvational-historical ‘status’” (“Antichrist” 562). It was this new pattern that accorded more fully with Joachim’s vision of history, for now each of his Three Status was able to have its own proper Antichrist.

The seven ages, as embodied by the seven heads of the dragon, still had a place in this tripartite system. But they now were made to serve the more expansive vision of Joachim’s Three Ages and showcase how much fuller his conception of time was than the previous models. Joachim, in his works on the Old Testament, demonstrated how the list could be expanded until all human history had its own Antichrists. Each group of Antichrists now led to one final, great Antichrist at the end of each of the Three Ages. This not only let Joachim argue that the Antichrist is a recurring phenomenon in history but also provided him with another avenue by which to reconcile his understanding of constant historical progression with his overarching vision of history divided into three separate Status. But more importantly, it gave him a chance to promote a larger perspective among Christians, encouraging them to see the eschatological struggle of good and evil not as a distant, unknowable event but as something that requires the active participation of the believer here and now.

For, whatever else it is, Joachim’s Antichrist theory is, like the rest of his system, a call for the faithful not to retreat from the world but to engage with it, not to withdraw inward but venture forth into an often-hostile world, to alleviate suffering and confront injustice wherever those things might be found. No matter what one thinks of Joachim’s model of history or the multiple Antichrists that inhabit it, his underlying call to action is one that modern Christianity, and the modern world as a whole, would do well to listen to.

Works Cited

Joachim’s work, De Septem Sigillis, is available in two Latin editions. One is included by Marjorie Reeves and Beatrice Hirsch-Reich in their article, “The Seven Seals in the Writings of Joachim of Fiore: With Special Reference to the Tract ‘De Septem Sigillis’” (Recherches de théologie ancienne et médiévale, July-December 1954, vol. 21, pp. 211-47), while the other has been edited by Morton W. Bloomfield and Harold Lee and published as “The Pierpont-Morgan Manuscript of ‘De Septem Sigillis’” (Recherches de théologie ancienne et médiévale, January-December 1971, vol. 38, pp. 137-48). The two editions are similar but not identical. The citations above are to the Reeves-Hirsch-Reich edition but I also consulted the Bloomfield-Lee edition while preparing this article. All translations mine.

For what it’s worth, Joachim’s method of mapping the openings of Revelation’s seven seals to specific and precisely defined epochs in the lifetime of the Church, as demonstrated in De Septem Sigillis, seems to be another of his great contributions to apocalyptic thought. While editing this entry I came upon this article from a website called Bibleinfo that interprets the seals along the same lines (albeit adjusted for the fact that we are living in the twenty-first century rather than the twelfth).

The other cited texts are:

Adso of Montier-en-Der. Epistola Adsonis ad Gerbergam Reginam de Ortu et Tempore Antichristi. Sybillinische Texte und Forschungen: Pseudomethodius, Adso und die Tiburtinische Sibylle. Ed. Ernst Sackur. Halle: Max Niemeyer, 1898. pp. 97-113.

Joachim of Fiore. De Ultimis Tribulationibus. Edited by E. Randolph Daniel. Prophecy and Millenarianism:Essays in Honour of Marjorie Reeves. Edited by Marjorie Reeves and Ann Williams. Essex: Longman, 1980: 175-189. All translations mine.

Lerner, Robert E. “Antichrist and Antichrists in Joachim of Fiore.” Speculum, vol. 60, no. 3 (July 1985): pp. 553-570. “Refreshment of the Saints: The Time After Antichrist as a Station for Earthly Progress in Medieval Thought.” Traditio, vol. 32 (1976): pp. 97-144.

Reeves, Marjorie: The Influence of Prophecy in the Later Middle Ages: A Study in Joachimism. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969.

The Book of the Prophet Ezekiel. The Oxford Study Bible, edited by M. Jack Suggs, Katharin Doob Sakenfeld, and James R. Meuller. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. pp. 857-912.

The First Letter of John. The Oxford Study Bible, edited by M. Jack Suggs, Katharin Doob Sakenfeld, and James R. Meuller. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. pp. 1547-1551.

The Revelation of John. The Oxford Study Bible, edited by M. Jack Suggs, Katharin Doob Sakenfeld, and James R. Meuller. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. pp. 1556-1575.