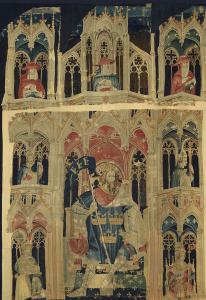

The Arthur myth has always had a complicated relationship with the Christian faith. On one hand, Arthur is most certainly a Christian king and a champion of Christendom. Indeed, he was, in medieval Europe, ranked among the “Nine Worthies,” a selection of nine rulers from history who were seen as exemplifying the virtues of proper kingship and warrior chivalry. The Nine Worthies were divided into a pagan, a Jewish, and a Christian triad; Arthur was one of the three Christian worthies. In the preface to his epochal edition of Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, William Caxton would even brag (with more than a hint of nationalistic pride) that Arthur was “first and chief of the [three] Christian men” (Caxton 816).

Arthur was generally portrayed as a militant champion of Christianity and enemy of its enemies. One of his earliest chroniclers, Nennius in the Historia Brittonum, speaks of how “Arthur carried the image of Saint Mary the eternal virgin on his shoulders” and achieved victory “through the strength of our Lord Jesus Christ and through the strength of the holy Virgin Mary his mother” (“Arthur and his battles”) in battle against the Saxons, while a near-contemporary text, the Annales Cambriae (Annals of Wales) contains the same story but instead claims that it was the True Cross itself that Arthur carried on his shoulders. Later Arthurian texts, such as the Alliterative Morte Arthure and Malory’s own work, would maintain this tradition by casting Arthur’s war against Rome as one of virtuous Christians against backsliding apostates. Thus, the image of Arthur as a heroic champion of Christianity is ever-present throughout the medieval tradition.

And yet, there is something about the Arthur mythos that does not quite sit well with traditional Christianity. There are, of course, the traces of pre-Christian Celtic elements that run through the stories, whether it be in the barely-disguised deities that populate Arthur’s court in the Welsh romances of the Mabinogion or the high medieval Grail quest’s apparent origin in ancient cauldron tales. But while these reminders of the pagan past are never far away, they were not the great source of concern for medievals that moderns like to think. After all, the reinvention of pre-Christian elements to serve a Christian milieu was a specialty of medieval and early modern authors. Dante and Milton had no problem utilizing their copious knowledge of Greco-Roman mythology in their decidedly Christian epics; they were more than capable of reshaping the classical material to a Christian message. The authors of the Arthurian tradition were able to do something quite similar, utilizing the Celtic elements in such a manner that the stories themselves largely stayed on the right side of orthodoxy.

However, there was a much more concerning element in the Arthur stories from an orthodox perspective and that was the idea of Arthur’s future return. The belief that Arthur had never died, that he was living still, and that he would come again to save Britain from catastrophe and inaugurate a utopian reign directly challenged Christianity’s claim that Christ’s own deathlessness and future return were completely unique. This, in turn, had the potential to raise questions about Christ’s divinity; if the act of escaping death and the promise of a future millennial reign could be repeated by another, then they could not stand as assurances that Christ is the only begotten Son of God. This was a very real concern for the medieval Church, especially given that the belief in Arthur’s return was apparently quite widespread. The tension between the two beliefs even boiled over in 1113, when a group of French churchmen visited Cornwall and attempted to explain that Arthur’s return was impossible because only Christ had the power to rise from the dead. The local population, descendants of Arthur’s own Britons, did not take kindly to this suggestion and began to riot. It is said that the clerics only barely escaped with their lives.

The myth of Arthur’s return was thus a legitimate source of anxiety for the Christian Church in the Middle Ages. Admittedly, Arthur was not the only historical figure whose return was hotly anticipated. As noted in the previous entry, the returns of Charlemagne, the Fredericks, and any number of other rulers, whether physically in the flesh or symbolically in a particularly promising descendant, were eagerly anticipated throughout Europe. This was especially true after the revival of the Last World Emperor prophecy in the Crusades and Joachim of Fiore’s subsequent redefinition of history as a series of recurring types and patterns provided such beliefs with a veneer of orthodoxy, however tenuous. Yet, whatever the fortunes of these various other return myths, they never seemed to inspire the same anxiety in the high places of church and state that the prospect of Arthur’s return did.

In part, this was no doubt because Arthur’s return also meant the national restoration of the descendants of the Britons—the Welsh, the Cornish, and the Bretons—and their reclamation of England for themselves. Thus, his return was always going to be a threat to the status quo, no matter how much the English themselves managed to domesticate it and turn it toward their own ends. The hoaxed discovery of Arthur’s grave at Glastonbury in 1191 was no doubt an attempt to settle the anxieties that the Arthur return prophecy created in the English ruling class. In some sense, the Celtic peoples of southern and western Britain were the first victims of England’s long colonialist project, and the myth of Arthur’s return, despite his concurrent co-opting by the English themselves, was an early form of anticolonialist resistance.

It is strange, then, that Arthur’s return only becomes aligned with the national resurgence of the Briton people after the Norman English had adopted the king as one of their own. The notion that Arthur never died and lives on to this day is authentically Celtic. The first hint of the idea comes from a tenth-century Welsh text, the Englynion y Beddau (Stanzas of the Graves), which announces that “unknown in the world is the tomb of Arthur” (Welsh text qtd. in Flood 93). This one line, admittedly, does not tell us much, only seeming to suggest that Arthur has no earthly grave. That this is because he is himself immortal is not spelled out. But it was clearly the most attractive explanation and the one that had become standard by the early 1100s, when the English historian William of Malmesbury remarked in his Gesta Regum Anglorum (literally Deeds of the Kings of the English, commonly called History of the Kings of England), “But the tomb of Arthur is nowhere to be seen, from whence ancient songs suppose that he is still to come” (Latin text qtd. in Flood 93). William’s testimony establishes that, soon after the Norman conquest, the belief in Arthur’s continued survival and future return was already well-established.

But the prospect of the return was not yet tied to that other great prophetic theme of the Welsh and Cornish; the future national restoration. Indeed, while early Welsh prophecy is replete with the hope of resurgence and the reclamation of the isle of Britain, national salvation is never attributed to Arthur. The tenth-century Armes Prydein gives credit to two rulers named Conan and Cadwallader, while other texts make mention of a mysterious mab darogan (“son of destiny”). Even Geoffrey of Monmouth, the man who introduced Arthur to a wider European public and gave the Arthurian story its basic narrative shape and structure, does not go this far. His Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain) did have Merlin promise that the Welsh would reclaim their ancient lands from the English—“Cambria [Wales] will overflow with joy, and the oaks of Cornwall will bloom. The island will again be called by the name of Brutus and what the foreigners call it [England] will fade away.” (Historia VII: 113-14)—and he did suggest the possibility of Arthur’s continued survival in Avalon—“And also that illustrious King Arthur was deathly wounded; he was carried from there to be healed of his wound in the isle of Avallon,” (XI: 81-4), but he did not combine the two ideas. Indeed, in his subsequent Vita Merlini (Life of Merlin), he both confirms that Arthur was alive and well in Avalon and outright states that this fact had nothing to do with the foretold restoration of the Britons. In that work, when Taliesin insists that, “send someone and compel the leader to return swiftly by ship … that he may drive off the enemy with his usual strength and restore the citizens to their former peace,” (Vita ll. 953-57). Merlin immediately rejects this idea, baldly stating, “Those people [the Saxons] will not withdraw in this way,” (l. 958). Instead, throughout Geoffrey’s work, it is once again Conan and Cadwallader who are credited with the coming restoration. Arthur is simply left indefinitely on Avalon, with no clue as to what his future holds.

In fact, despite it becoming something of a commonplace that it was the descendants of the Britons who were awaiting Arthur’s return, the first actual linkage of his return to the idea of national salvation seems to come from an English source and refers to a specifically English national restoration. That English source is the Brut, an English-language translation and expansion of Geoffrey’s Historia composed by Layamon around 1200. There, not only does Layamon have Arthur himself enthusiastically promise to return “and dwell amongst the Britons with greatest joy” (Brut l. 14283) but he in his own voice states that “there once was a wiseman called Merlin, he said—and his prophecies were truth—that an Arthur should come to help the English” (ll. 14296-98). Thus, not only is the literary association of Arthur’s return with national restoration made comparatively late in the tradition, but it is made with the English and not the Celtic peoples in mind.

What this leaves us with is a paradox. As Caitlin R. Greene rightly notes in “‘But Arthur’s Grave is Nowhere Seen’: Twelfth-Century and Later Solutions to Arthur’s Current Whereabouts,” “whilst there is no hint of a link between Arthur’s return and the expulsion of the English in pre-Galfrydean literature, both his deathlessness and potential return (for an unclear purpose) are referred to” (Greene, “‘But Arthur’s Grave is Nowhere Seen’”). Thus, there is an authentically Celtic tradition of Arthur’s return but not of that return including the prospect of national salvation. What then is Arthur going to do when he comes back, if not save his own nation (whether defined as the Britons or as England) from calamity? If being the savior of his own country is off the table, what is the purpose of his prolonged survival and promised return?

I think that it is very likely that Arthur’s return was, in its original form, a direct outgrowth of the myth of the Last World Emperor as found in the Apocalypse of Methodius. Indeed, Arthur was an ideal candidate. His chief claim to fame was, at least until Geoffrey, as a champion of Christendom and a resolute pagan-fighter. It is true that there was always a national dimension to Arthur’s campaign against the pagan Anglo-Saxons but, as noted above, both of our two earliest sources for the shape of Arthur’s career, Nennius and the Annales Cambriae, already cast his victories as victories for Christianity and suggest that his personal piety is crucial to these successes. The Emperor’s chief role was to be as a defender of the faith against enemy religions and that was something that Arthur had a proven track record in. Indeed, the Annales Cambriae went so far as to claim that, rather than an image of the Virgin Mary (as in Nennius), “Arthur carried the cross of Our Lord Jesus Christ” (Annales Cambriae 9) itself into battle, giving him the direct connection to the True Cross akin to the one that Pseudo-Methodius and the Tiburtine Sybil give to the Last Emperor.

What is more, the fact that the Last Emperor was to be a Roman Emperor was also a mark in Arthur’s favor. Without getting into modern theories that the historical Arthur may have been culturally Romano-British and seen himself as restoring the empire, there is a persistent tendency for the Britons to see themselves in legendary lore as kinsmen or heirs of the Romans. The famous legend of the Britons’ descent from Aeneas and his Rome-founding Trojans is chiefly associated with Geoffrey of Monmouth, but appears as far back as Nennius’s Historia Brittonum and the Annales Cambriae. Welsh literatary tales such as the Dream of Macsen Wledig (found in the Mabinogion) told of how British heroes had claimed the Roman throne in the past. Thus Arthur would certainly have had the lineage to make the imperial claim and sit upon the throne as the final Roman Emperor in the end of days.

For, indeed, while the early chronicle accounts present Arthur as an insular war leader chiefly concerned with the invading Saxons, hints from the Welsh tradition suggest that he was early on believed to have a more expansive scope, that he was in fact already viewed as a “world emperor” like the final monarch foretold in Pseudo-Methodius. Various medieval Welsh texts refer to him already as “the emperor” and Culhwch and Olwen, one of the early Arthurian narratives found in the Mabinogion, notes that Arthur has had adventures “in India the Great and India the Lesser … in Europe … in Africa, and the islands of Corsica” (How Culhwch Won Olwen 182), painting him as a figure whose influence spanned the known world. Even more strikingly, Culhwch also claims that Arthur “conquered Greece in the east” (182). This means that, at least in the Welsh imagination, Arthur would have quite literally have been a “King of the Greeks,” the title which the Last Emperor is most commonly called by in both Pseudo-Methodius and the Tiburtine Sybil.

Thus Arthur was eminently qualified to fulfill the role of the Last World Emperor. Indeed, it is possible that some of the elements cited above were added to his narrative specifically to spruce up his Last Emperor credentials, once the already-existing similarities were noticed. Furthermore, the mere fact that Psuedo-Methodius had specified that the Last Emperor would be “he whom men had supposed to be dead and good for nothing” (Pseudo-Methodius 13:11) made it necessary for the Last Emperor to be someone who had defied death in some way, someone whom it was natural to suppose would be dead but was in fact alive. As a figure of the fifth or sixth centuries, Arthur would certainly have fit that bill for ninth-century Britons. Given his other qualifications and a healthy dose of national pride in their greatest hero, it is not surprising that they should have looked at Arthur as a fitting candidate for the Last World Emperor, with the Last World Emperor myth in turn reshaping Arthur’s own legend and creating the conviction that Arthur, as “he whom men have supposed to be dead” was still alive and biding his time until a messianic future return.

Much has been made about the supposed deviations from mainstream Christianity of Britain’s “Celtic fringe,” in areas such as Wales, Scotland, and Cornwall. Most of this is overblown. The Celtic peoples of the region were not as inclined to heterodoxy as has often been claimed. Thus, it is not necessary to assume that the belief in Arthur’s return had its roots in a heterodox or non-Christian source. It is certainly true that the Apocalypse of Methodius had some decidedly non-orthodox ideas buried within it, but for over a thousand years it was tolerated and sometimes actively endorsed by the Church as a legitimate account of the end-times. Thus, Pseudo-Methodius offered the descendants of the Britons a legitimate means of importing Arthur into the Christian scheme of the future and giving him immortality to boot.

The notion that the return myth began as a way for the ever-threatened descendants of the Britons to claim the Last Emperor legend as their own is supported by Victoria Flood’s contention, in “Arthur’s Return from Avalon: Geoffrey of Monmouth and the Development of the Legend” that the notion of Arthur’s immortality and future return first arose amongst the continental Bretons in the ninth and tenth centuries (see Flood 91-93). Given Brittany’s location as adjacent to and then part of France, the Bretons were well-placed to receive the narrative of Pseudo-Methodius from the learned centers of France and Italy, were it had been circulating since at least the eighth century. Thus, in terms of proximity and time, the Arthurian return myth fits in as an outgrowth of the already popular and widely circulating myth of the Last Emperor. What is more, the text Flood cites as evidence for a Breton origin to the return myth, Hériman de Tournai’s De miraculis, begins its account of the above-mentioned Cornish riot of 1113 with the words, “just as the Bretons are accustomed to quarrel with the Franks about King Arthur … saying that Arthur still lives” (Latin text qtd. in Flood 91). This statement suggests that the Breton claim that Arthur is still alive and would someday return emerged out of a dispute with the Franks, possibly over the rule of Brittany itself. As demonstrated in our previous entry, the Franks were by the tenth century in the habit of claiming that the Last Emperor would be one of their line in order to justify their own imperial ambitions. To argue instead that the returned Arthur would be the Last Emperor would directly challenge the Franks’ own claim to the title, as advanced by the likes of Adso of Montier-en-Der, and thereby nullify the territorial claims to places such as Brittany that went along with it.

Thus, there is ample reason to think that the myth of Arthur’s return was an adaptation of the legend of the Last World Emperor to the specific political situation of the descendants of the Britons after the rise of England and France left them perpetually endangered. The Welsh, the Cornish, and the Bretons faced both the physical danger of conquest by these more powerful nations but also the existential danger of being sidelined in the grand narrative of history. To claim the mantle of the Last Emperor, Christianity’s other messiah and the great hero of the end-times, served to counter both of these dangers. And it was natural that as the last great hero of pan-Briton resistance, Arthur would fulfill this role. Given the apparent proximity of the first manifestations of the return myth in both space and time to the political adoption of the Last Emperor narrative of Pseudo-Methodius by the Franks and others, it seems probable that the descendants of the Britons took over the Last Emperor idea as a form of resistance to their oppressors, arguing that the Christian scheme of history, as now embodied in the figure of King Arthur, actually gave them pride of place and told of their inevitable survival in the face of physical and cultural annihilation.

This would make the Arthur return myth both an anticolonialist response to and appropriation of an idea, that of the Last World Emperor, that more often seems to enter the historical narrative as an excuse for colonialist expansion and oppression. This reveals a remarkable new aspect to both the Arthurian return myth and the Last Emperor narrative that has previously gone unnoticed. But my argument that Arthur was viewed as the long-awaited Last Emperor also provides an answer to some of the outstanding questions surrounding Arthur’s portrayal in the canonical Arthurian texts of the high medieval period, including the works of Geoffrey of Monmouth and Malory. It is to those works, and the ways in which they identify Arthur with the long-awaited Last Emperor, that we shall turn to in our next entry.

A Note on Sources

Many of the works cited below are in Latin, and the Stanzas of the Graves is in medieval Welsh. The English translations above are my own, with the exception of the Mabinogion, for which I have relied upon Sioned Davies’s translation. I have also translated Layamon’s early Middle English and rendered Caxton’s early modern English into a more readable contemporary form.

Works Cited

Annales Cambriae: The C-Text. Ed. Henry W. Gough-Cooper. Welsh Chronicles Research Group, 2015. http://croniclau.bangor.ac.uk/documents/AC%20C%20first%20edition.pdf

Apocalypse of Methodius (Pseudo-Methodius). Apocalypse Pseudo-Methodius | An Alexandrian World Chronicle. Ed. Benjamin Garstad. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Caxton, William. “Prologue and Epilogue to the 1485 Edition.” Le Morte Darthur. By Sir Thomas Malory. Ed. Stephen H. A. Shepherd. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004.

Flood, Victoria. “Arthur’s Return from Avalon: Geoffrey of Monmouth and the Development of the Legend.” Arthuriana 25.2 (2015): 84-110.

Geoffrey of Monmouth. The History of the Kings of Britain. Ed. Michael D. Reeve. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2007. Vita Merlini. Ed. John Jay Parry. Urbana: University of Illinois, 1925. Sacred Texts [I have been warned against an over-reliance on this website but, alas, the Latin text of the Vita Merlini is quite hard to come by]. http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/eng/vm/vmlat.htm

Greene, Caitlin R. “‘But Arthur’s Grave is Nowhere Seen’: Twelfth-Century and Later Solutions to Arthur’s Current Whereabouts.” Arthuriana, 2009. http://www.arthuriana.co.uk/n&q/return.htm

“How Culhwch Won Olwen.” The Mabinogion. Trans. Sioned Davies. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Layamon. Brut. Ed. G. L. Brook and R. F. Leslie. London & New York: Oxford University Press, 1978. Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan, 1993. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/cme/LayCal/1:143?rgn=div1;view=fulltext

Nennius. “Arthur and his battles.” Historia Brittonum. http://www.historiabrittonum.net/?page_id=72