The end of the world, it seems, is always upon us. Constantly, we are warned to expect the imminent arrival of any number of Armageddons. Many Christians, particularly of the evangelical variety, continually reassure us that they will soon be raptured to Heaven and the rest of us left to suffer the manifold calamities of the end-times. On the other side of the spectrum, scientists and other secular-minded individuals have also begun to take the end of the world, or at least the end of the world as we know it, quite seriously. In this, they see natural forces and human idiocy as the main culprits rather than the will of God. But they share the same sense that human history is reaching a disastrous point of no return.

In some ways, this pessimistic spirit infects us all. The extreme and often bizarre weather transformations wrought by climate change are increasingly a part of daily life. And all of us have had our lives disrupted by a global pandemic that shows no signs of abating. Current global conditions are now so worrisome that few would dare to imagine anything other than a grim escalation of them in days to come. Across the world, the prospect of the future inspires far more fear than hope. Why have hope, after all, when all signs point to the future being an intensification of present turmoil? Apocalypse is no longer a distant event in the long span of time or merely an intriguing setting for a work of speculative fiction. All of us live the apocalypse, all the time.

Not everyone may share the general sense of pessimism or be particularly concerned for the future. But there can be no denying that the tenor of our times is apocalyptic. Anyone hoping to engage with society at large must acknowledge this fact. Anyone seeking to shape the public future must recognize that, for so many today, the future is a thing to be feared or rejected rather than welcomed. Whether we ascribe to apocalyptic thinking ourselves or not, we must all wrestle with its power and influence on the modern world. Thus, it behooves us to understand the origins of apocalypse, how it has shaped the major movements in history, and what lessons its earlier phases have for grappling with our own apocalyptic moment.

For most of human history, conceptions of the future and of the end of the world—and these were more often than not the same thing—have been defined by religion. Indeed, it is religion that birthed the notion of apocalypse and, with it, the belief that things to come would be different from things as they currently are. This latter notion, the belief that there is meaningful change through time, is the necessary prerequisite for a proper understanding of the future as a temporal state distinct from both the past and the present. And this sense of futurity was first developed and cultivated by the religious expectation of coming cosmic transformation. Thus, it was out of religion and its apocalyptic ideas that the very concept of “the future” was born. Indeed, for thousands of years, the business of imagining the future remained almost exclusively the preserve of religion and of those who took religion seriously.

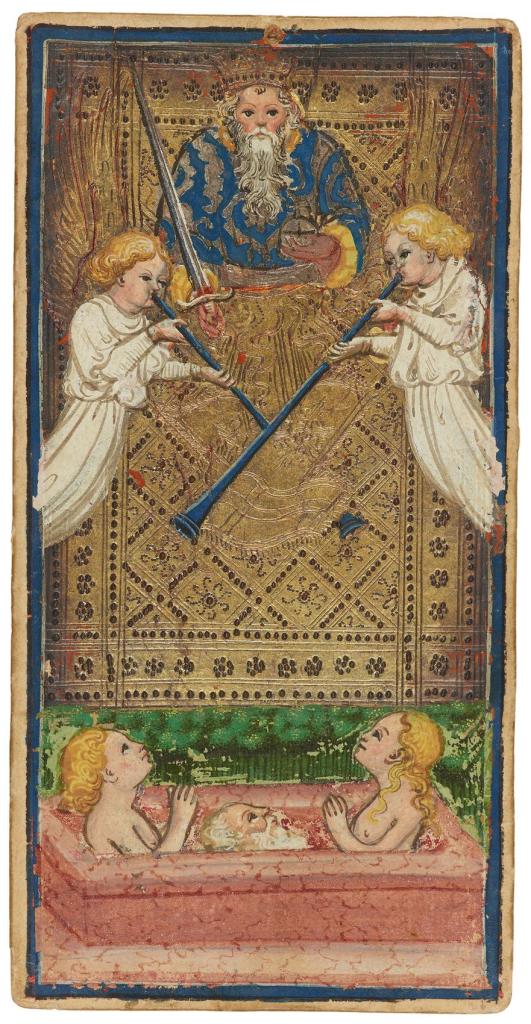

Nor have we—however much we may pride ourselves on being modern, liberated, and secular—freed ourselves from the religious sense of apocalyptic futurity thus bequeathed to us. After all, the word “apocalypse” itself comes to us from the Greek title of the Bible’s final book, Revelation, where it indicates not calamity and destruction—though, of course, the Book of Revelation has no shortage of those—but an unveiling of future things. While the common usage of “apocalyptic” as the default descriptor of our times more often calls to mind sensationalistic terrors, there is still some resonance of the original religious meaning nestled within it. And if the work of eminent scholars such as Marjorie Reeves, Bernard McGinn, and Delno West have taught us anything, it is that the modern world itself was born in the writings of an apocalyptic prophet in twelfth-century Calabria. All in all, we are still very much conditioned by what religious people down the centuries have thought about the future and thus their thinking is still very much relevant to how we understand our present and its future possibilities.

But there is an even better reason to acknowledge the relevancy of these traditions: when it comes to the recognition of future possibility, religious thought has modern apocalypticism beat and the contest is not close. It is true that many individuals and groups, mostly holdouts from the last New Age boom in the 1960s and 1970s, still look forward to the Age of Aquarius and other such visions of hope. But the general outlook on our apocalyptic future is one of despair. The forecast is dismal; things will just keep getting worse until God, nature, or humanity’s own boundless stupidity brings the final curtain down. This is not what we find in most religious stories of the future. It is true that nearly every religion is eschatological—concerned with the ultimate fate of the world and human beings—in some form or another. But very few, if any, religions are utterly pessimistic. Indeed, for all the doom and gloom which seems to spew out of apocalyptic texts like Revelation, the general religious attitude toward the future and last things is one of potential, of social transformation and, above all, of hope.

For religions around the world have long recognized that, despite all the terrors that future events threaten to serve up, what they bring is not so much an end as a rebirth: the rebirth of the world, of society, and of humanity itself. Destruction, when there is destruction, is not meaningless and punitive. Rather, it serves to open the way for something new to begin. It was largely in the field of eschatology—the thought and study of Last Things—that new modes of social organization, new methods of societal reinvention, and new answers to society’s problems were imagined and explored for the first time. For it was in the future that the one thing which has always eluded and continues to elude human society—justice—could at last be found.

This allies eschatology closely with another central concept in the history of human thought, that of utopia. Indeed, the two have always been closely intertwined. It has, for most of human history, been impossible to think of the final, teleological future without imagining it to include a society set up to function as society was always meant to, in a just and fair manner. And it has just as often been impossible to think of utopia without also hoping that the ideal social structure found therein will someday spread throughout the earth. For both eschatologists and utopians, the future has long been a place that, while not lacking in dangers, offers an opportunity to make a better and more just world. For them, what the future ultimately offers is a sense of hope.

This sense of hope is severely lacking in our own days. For the first time, humans en masse are contemplating the prospect of apocalyptic catastrophe without a corresponding movement toward justice, renewal, and societal transformation. And yet, justice, renewal, and societal transformation are the things we now seek after most as a society or, at least, they are the things whose lack we most acutely feel. The widespread embrace of and activism for social justice, especially amongst the younger generations, over the course of the last few years demonstrates as much. And yet, there seems to be little hope that such justice can ever be achieved in a world perpetually on the brink of apocalyptic terror and collapse.

But if there is one thing that religious thought has to teach us about the future, it is precisely how creative and fruitful such a moment can be. As noted above, contemplation of things apocalyptic has long led, in the religious traditions, to new ideas about how to better rebuild society and meet our justice deficit. From Joachim of Fiore in the late twelfth century to Jürgen Moltmann in the later twentieth, thinkers who have thought through the future from a religious perspective have produced powerful visions of social justice and hope in the face of crisis and calamity. Modern thinkers who wish to save, or at least somewhat improve, our apocalyptic modern world have much to learn from their example.

The purpose of this column is to encourage moderns to do just that. It is my intention to explore how various religions around the world, as well as religion-adjacent philosophies and literary traditions, have thought about the future, the world’s ultimate destiny, and utopia. But this column is not a place to find doom-and-gloom sensationalism, nor is it a roadmap to the end of days. You can find that in plenty of other places if such is your fancy. My purpose here is not to suggest that the end is nigh, but to look at the intersecting threads of prophetic, eschatological, and utopian thought as the most longstanding expression of the innate human desire for cosmic and societal justice, and as an arena for brainstorming what a truly universal kind of justice might look like. Naturally, Christianity will loom large over this investigation, as it has in this first article. But I also intend for the scope of this column to extend far beyond the Christian West, the world’s other religious traditions have their own insights and perspectives toward the possibility of future justice and social transformation. It is my hope that, through these explorations, this column will encourage both believers and secularists to take heart despite the challenges ahead of us, and to face them with a courageous sense of potential and possibility rather than dread and fear.

I would like to close this first entry with an explanation of the name of my column. “In Newest Days” is a literal translation of the Latin “in diebus novissimis.” For medieval writers, this phrase had a double meaning. the “newest days” referred to could simply be the most recent days to have occurred from the author’s own perspective. Thus, a writer could speak of a notable event that had just occurred as happening “in diebus novissimis.” But the phrase “in diebus novissimis” could also designate the “newest days” that would ever be, the final days at the end of the world. While this remarkable double valence perhaps says something important about how the medieval mind conceived of the future, it is even more apt as a symbol for the apocalyptic tone which we so often strike when we discuss, think about, and intervene in the developments of our own time. But the ease and grace with which “in diebus novissimis” brings the present moment into conversation and proximity with the whole history of apocalyptic imaginings also makes it a suitable name for a column that seeks to do something similar. Indeed, over the coming weeks and months, I shall attempt to accomplish in so many words what this little Latin saying does in so little. It is my hope that you will join me as we investigate how religion has throughout history formed and reformed our understanding of the shape of things to come.