I have been starting to get into the thought of the great 20th century Catholic philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand, and so I found this very good conference put together by the ever-stalwart Franciscan University of Steubenville on his thought.

A fascinating moment in particular was this discussion of the thought of Karol Wojtyla (who was very influenced by Hildebrand) on sexual shame, and Wojtyla’s defense of sexual shame.

That was very interesting to me, in part because Pope St John Paul II’s theology of the body is often thought of as an attempt to “sex-positivize” the traditional sexual doctrine of the Church, so seeing the philosopher Wojtyla mount a defense of sexual shame is interesting in and of itself, and, let’s face it, in large part because I enjoy me some good old-fashioned #CatholicPitches. We’re often told that sexual shame is bad, that it’s the product of the Bad Old guilt-inducing pre-Vatican II Catholicism that we’ve now thankfully moved past. On an issue like sexual shame that’s something I’m inclined to agree with–but this is precisely why I need to look at potential correctives, because, if one believes in the Holy Spirit, then one has to think that previous centuries do have something to teach us.

So, what does Wojtyla’s defense of shame consist of?

The first is that shame is a dimension of interiority. Animals do not feel shame. They feel fear, but not shame. Shame, therefore, is an aspect of our subjectivity which is constitutive of our humanity. While animals (and Nietzsche) recognize only good/bad, safe/danger, we recognize good/evil, and feel shame. To try to completely ignore or transcend shame is then to try to erase something which makes us profoundly human. To feel shame is to have the capacity to interiorly meditate and contemplate on our actions and act on the basis of our rational will rather than our animal instincts.

In the sexual sphere, then, for Wojtyla, shame is very often the product or consequence of objectification. The shame that a woman feels when she exposes herself indecently, or that a man feels when he acts lustfully towards a woman, is the shame of objectifying the other, of considering them as a means and not an end in themselves, as an object. Therefore, again, we find that shame calls us back to our full humanity. It resists the objectification of oneself and of the other.

Finally–a theme near and dear to Wojtyla’s heart–sexual shame reminds us that we are an integration of body, soul and spirit, and not souls incidentally connected to meaningless bodies. As has been noted, shame is intrinsically spiritual since it is a part of the interior subjective dimension which transcends the animal, yet at the same time it is inseparable from our bodily dimension.

Shame, then, functions as a sort of moral warning system. Against the rational mind which is always so ready to produce rationalizations for disordered acts, shame functions as a sort of emotional alarm system which can call us back to true rationality, which is the ordering of our wills towards the good. Wojtyla takes the example, not of premarital sex, but of a married couple who, even though “technically” they have not been sinning sexually, have been drifting apart from each other, and for whom sexual union is no longer mutual self-gift in love but merely the satisfaction of bodily urges; that married couple might suddenly start feeling sexual shame again, and this would be a call unto them to reinvigorate their union. Shame, then, can be the voice of a conscience that we would too hastily bury and will not let us.

Of course, this alarm system can produce false positives as well as false negatives. This is why–and this is where his thought evades easy caricature–Wojtyla stresses the importance of the education of shame. Small children, as is well known, literally feel no shame. (My daughter is in the “Pee! Poop!” stage right now.) Shame is therefore something that is inculcated (in the etymological sense) in us, and therefore Wojtyla easily recognizes that shame can be miseducated. But, Wojtyla notes, this miseducation goes in both directions. There are cases, of which modern society is hyperaware, where we feel shame even though we should not; but there are also cases where we do not feel shame, and perhaps we should. So while Wojtyla sees the many problems of a puritan culture of sexual shame, he sees the problem as not shame itself, but rather the miseducation of shame. Like all of our human faculties, shame needs to be educated in order to be ordered towards the good.

Now, what do I make of all this?

In part I think these are all points well-taken. I particularly like the idea of shame as a moral “early warning system”, although I would still lay a stress on all the ways this system can be “buggy.” The point about shame being an important part of our subjective interiority, and therefore not so easily dismissed less we become more animal, is well taken.

That said, in Wojtyla’s thought on sexual shame there is also some of his annoying essentialism; he analyzes the different ways in which boys and girls feel shame and phenomenologically raises them up to intrinsic sexual differences, which, to say the least, is perilous. He also draws into discussions of things like appropriate clothing, where it’s hard to think that a Polish pastor and an equally orthodox, say, Brazilian pastor, wouldn’t reach different conclusions.

My main critique, and it is a critique in the proper sense (and I don’t know if this is an issue with Wojtyla himself or just the scope of the discussion I watched), would be to say that Wojtyla speaks almost exclusively of the interior dimension of shame, but I think there is also a social dimension of shame, which, from the point of view of the Gospel, is much more problematic.

Shame can be an interior moral warning system, but it is also–is this debatable?–a form of social control; and given the reality of original sin, every society will shame things that ought not to be shameful. We can all come up with many examples. No doubt, Wojtyla would agree and say that this is the problem of the miseducation of shame, and this is indeed true as far as it goes, but are we allowed to stop here?

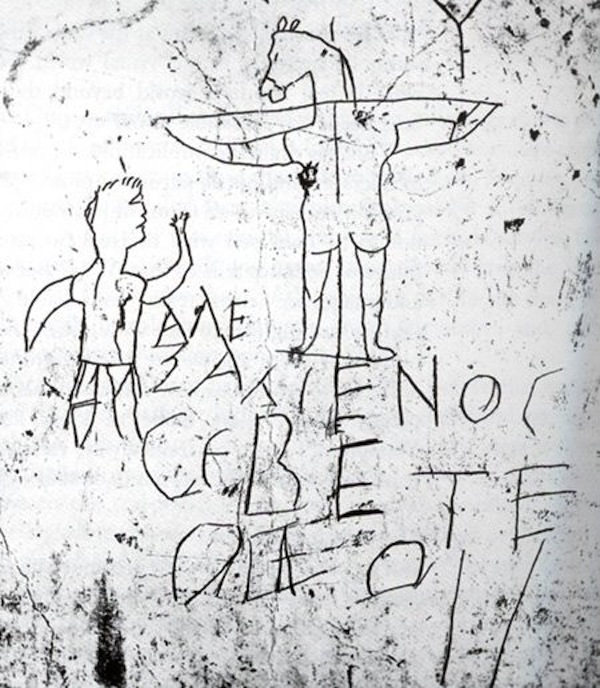

After all, the most shameful thing in the entire pagan Greco-Roman world was the cross. They were everywhere but, as Cicero writes, they were just not talked about. And most pagan criticisms of Christianity revolved around their shamelessness: the gall with which they held up this most shameful of symbols, as a mirror to the world and a sign of contradiction. Paul writes masterfully about his shamelessness for the Gospel. It is folly to the Greeks and a scandal to the Jews, and yet he wishes to do nothing but preach Christ and him crucified.

I think of the story of the woman taken in adultery, which is in many ways a story about shame, and about the way that shame can be used for the purposes of scapegoating, and as a weapon of the (culturally) strong against the weak and the outcast, a weapon all the more powerful and pernicious because it fires its arrows from inside the victim. But the story is not so univocal, because what does Jesus do if not shame the accusers of the woman into dropping their rocks?

Miseducation and education of shame, yes, yes. But, perhaps there is also a need for a discourse of how Christians can be called to “shame shame”, to in the mode of the divine jiu-jitsu that makes the Cross a victory, turn shame, at least in its social dimensions, against itself.

EDIT: You should read this meditation on shame by Eve Tushnet.

Image: “Alexamenos worships his god“, the earliest known anti-Christian graffiti, depicting Christ on the Cross as an ass. Shame is one of the earliest enemies of Christianity…