At the tail end of an excellent post explaining why it’s perfectly consistent for pro-lifers to say “abortion is murder” and not want to guillotine anyone who procures abortions, my good friend Noah Millman makes the frequently-heard point that the American pro-life movement is corrupted by its coeval relationship with the Republican Party:

To me, the story [Noah’s post riffs off of] says little about the sincerity of the beliefs of those who oppose abortion. It says a great deal, though, about the corrupting effects of partisan politics on moral crusades, something I’ve harped on before in this space. I really, really do believe that the more seriously you take the proposition that abortion is categorically immoral, the more morally imperative it is for you not to hitch your wagon to the star of either political party. Nothing is more corrupting of the anti-abortion cause than its subsumption into a culture war that is fundamentally – fundamentally – about making it easier for politicians to get re-elected.

This is a point that is often heard, and for which I have a tremendous amount of sympathy. I am a supporter of the Republican Party, but this “allegiance” takes a far, far seat behind my allegiances to the pro-life cause and, more generally, Christianity itself. It is true that partisan politics is inevitably corrupting (the question is to what extent, and what amount is tolerable). It is true, furthermore, that as a matter of brute political strategy, the worst thing for an interest group (which is what the pro-life movement is) is to be able to be taken for granted by a political party. Those interest groups that get parties to bend over backwards for them are those that have a foot in both parties, and can swing either way (thereby deciding elections). If group X feels that it has no choice but to vote for party A (and party A knows it), then party A really doesn’t have to do anything for group X. (cc: African-Americans, but this is another topic)

And finally, yes, there is something not only instrumentally but fundamentally shocking about the pro-life movement, whose cause is righteous and holy, functioning, in the end, as a machine for getting politicians reelected.

So, again, Millman’s critique is one for which I have tremendous sympathy.

But with all that being said, there are some points which seem to me unavoidable, and which critiques along Millman’s line almost never mention, let alone take into account. To me, these points don’t necessarily vitiate the critique, but I do wish those who make the critique would take them into account. They are the following:

In the United States, abortion policy is decided by the Supreme Court. In 1973, five seven Justices of the United States Supreme Court decided, with absolutely no basis in American constitutional law, that abortion-on-demand at any point in the pregnancy was a constitutional right. All of our debates really happen in the tiny shadows of this massive elephant-in-the-room. The job of any movement that would seek to reverse this status quo, if only to return the issue to the democratic process, therefore, is not to cobble together some coalition in Congress; it is, rather, to get the right justices appointed to the Supreme Court. In the case where your job as an interest group is to get a coalition together in Congress, bipartisanship is a feature and not a bug. In the case where your job is to get judges appointed, and given the political realities of the United States, where committed pro-lifers are a plurality but not a majority of voters, it is hard for me to see a viable strategy for the pro-life movement that looks anything other than this: (a) become strong enough in one party that it will nominate pro-lifers; (b) get pro-life Presidential candidates elected; (c) get good justices on the Court. This strategy has been enormously frustrating (there are five Republican-appointed Justices on the Court, and Roe is still the law of the land), but it is hard for me to see an alternative. In any case, any critique of the partisanship of the pro-life movement, though most welcome, nonetheless has, I think, to take this reality into account.

The story of the pro-life movement and partisanship is the story of pro-lifers pushed out of one party. In the conventional story of the pro-life movement and the Republican Party, the story is relatively straightforward: incensed by Roe, pro-lifers and Evangelicals launched a takeover of the already (mildly) conservative GOP in order to take over the US government and fix everything. But this isn’t the story, or rather, it’s only the second half of the story. The first half of the story is that the Democratic Party, seeing affluent social liberals and women (missing the fact that women are more pro-life than men, but this is another story) as key to its new coalition following the breakup of the old New Deal coalition, became absolutist in its pro-abortion positions. The story of Ted Kennedy and Jesse Jackson’s notorious flip-flops on abortion is well-known. As is Mario Cuomo’s infamously astonishing “personally opposed” speech. As is the exclusion of Bob Casey, a popular governor of a major swing state, from the platform at the Democratic National Convention. The story of pro-life partisanship, then, is, at the very least, as much a story of the pro-life movement being driven out of one major party as it is one of the pro-life movement tying itself to the mast of another party. Pro-choicers have always been much more at home in the Republican Party than pro-lifers have been in the Democratic Party (especially actual pro-lifers, and not Democrats who call themselves pro-life and vote with the pro-choice lobby on most issues, like e.g. Harry Reid, Bob Casey Jr, et al.). While no one denies that polarization has increased in American politics of late, it is still impossible to swing a cat through a roomful of Republican operatives without finding a dozen who will say (absurdly) that the GOP’s ticket to victory is jettisoning the pro-life platform, nor is any journalistic story on the GOP’s travails complete without on-background quotes from senior Republicans to that effect. How many senior Democrats are going around saying that if only the Democrats went pro-life, they’d win a permanent majority? (Which is actually a much more cogent case politically than the case for a pro-choice GOP.) Any critique of the partisanship of the pro-life movement should have some notion of how to fix the Democratic Party’s unremitting hostility to the pro-life cause. Which brings us to…

The Democratic Party’s moves (such as they were) towards the pro-life movement were the result of conservative victories. The only times when the Democratic Party broke (however symbolically) with its pro-abortion orthodoxy were moments when social conservatism were seen as dominant in American politics. They were Bill Clinton’s “safe, legal and rare” lines, and the DNC and DCCC’s efforts in the 2004 and 2006 election cycles to recruit explicitly pro-life (or, “pro-life”) candidates. Whatever their merits, these moves all proceeded from the same logic: the pro-life coalition had delivered serious victories to the Republican Party (or, more accurately, the dogmatism of the Democratic Party’s support for abortion had turned off too many crucial moderate voters), and the Democratic Party had to change to reflect that. Political parties, like other bureaucracies ruled by self-interest, only change when they experience failure. Even though it would be in a foe’s self-interest to make peace without war, human nature is such that all too often the foe will only come to the negotiating table after having been defeated. For very obvious reasons, I would very much like for the pro-life movement to find a “second home” within the Democratic Party. But history, at the very least, seems to strongly suggest that the best way for that to happen is for the pro-life-GOP alliance to win decisive electoral victories.

Again, I have tremendous personal sympathy for critiques of the partisanship of the pro-life movement. My allegiance is to the pro-life movement first, and the Republican Party second. It is precisely because I want such critiques to be as strong as they can be that I wish they took these points into account.

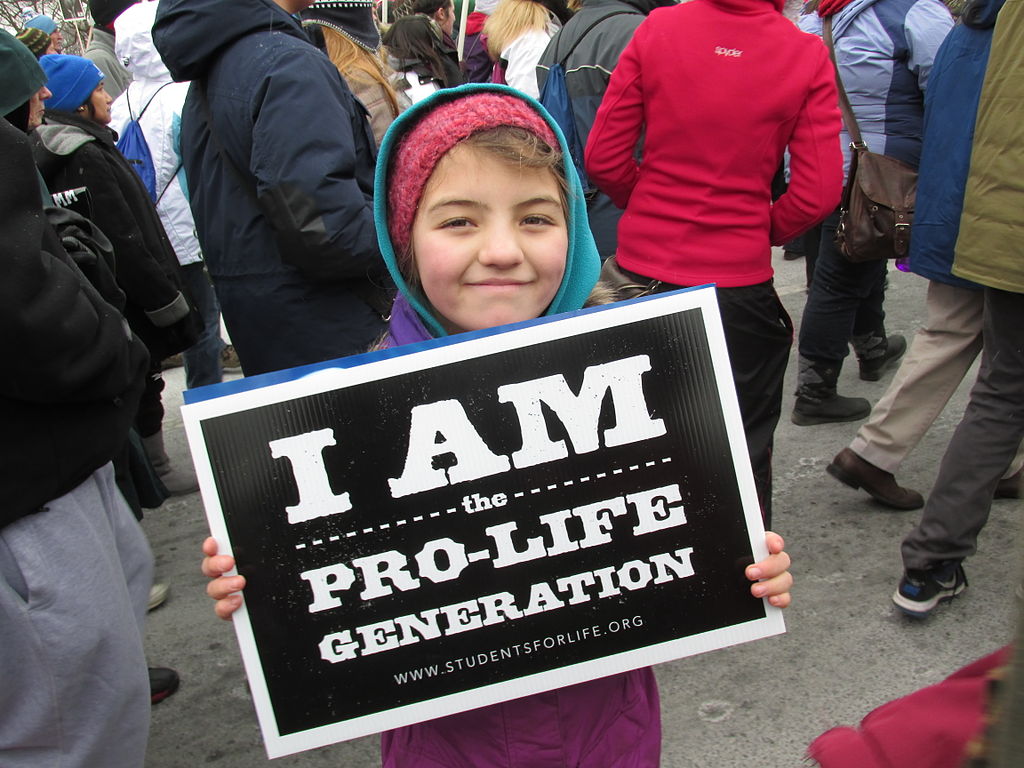

Photo by Miss.Monica.Elizabeth (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons