On a trip, have you ever come across something so totally unexpected that it seems a bit like a mirage? I felt that way when we came upon Saint Meinrad Archabbey in southern Indiana. We were driving along through the standard Midwestern landscape of woodlands and farms, and then suddenly–poof! There’s a spectacular church that looks like it could have been magically transported from Europe.

I was on the lookout for Saint Meinrad at the suggestion of a friend who’s taken classes in its school of theology. She told me it was beautiful, but I was taken aback by its size and grandeur. Who would have thought such a treasure exists in a sparsely populated corner of the Midwest?

The designation”archabbey” is an indication of Saint Meinrad’s importance, for there are only two Roman Catholic archabbeys in the United States and just eleven in the entire world. I felt a little like Dorothy in Oz as I wandered through its buildings on a self-guided audio tour (the abbey’s visitor center has digital players that allow you to tour at your leisure). There was so much to see and admire.

The monastery was founded in 1854 by Benedictine monks from the thousand-year-old monastery of Einsiedeln in Switzerland. The monastery became a center for the training of priests, which it continues to do to this day. It’s named after Meinrad, a ninth-century saint who is known as the patron of hospitality because he was murdered by wandering thieves (yes, I realize that’s not exactly a ringing endorsement for being welcoming to strangers, but I don’t decide such things, I just report them).

The present church, a Romanesque structure, was built between 1899 and 1907. Its massive walls are made from hand-chiseled sandstone carried by mule-drawn wagons from a quarry a mile away. Because this is a monastic and not a parish church, its interior has choir stalls that face each other but no permanent pews. The rest of the space is open so that a variety of seating arrangements can be accommodated.

About a hundred monks live at the archabbey, staffing a seminary and graduate-level theology school for priests, deacons and lay people. They also operate Abbey Press, which produces books, gifts, cards and gifts, and Abbey Caskets, which makes handcrafted coffins and urns. As Benedictines, the monks make vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. Following St. Benedict’s command to receive all guests as if they are Christ, hospitality is also part of the abbey’s mission. Its retreat center has 31 rooms and welcomes pilgrims for guided and self-directed retreats. Guests are welcome to join the monks for the five daily services that make up the Liturgy of the Hours.

Another indication of Saint Meinrad’s importance are the three shrines in its church. Just inside its front door is the Shrine of Our Lady of Einsiedeln, the patroness of the church. The statue is a replica of a black madonna and was given by Saint Meinrad’s mother abbey in Switzerland (these dark-skinned images of the Virgin Mary were common in medieval Europe). The second shrine honors Saint Meinrad and the third is the Shrine of All Saints, which houses the archabbey’s collection of saints’ relics.

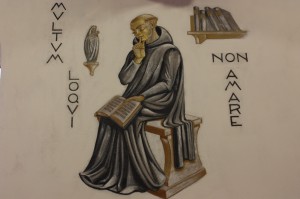

Part of what surprised me about Saint Meinrad is its mix of traditional and more contemporary iconography. Much of the latter was created in the 1940s by Dom Gregory de Wit, a Belgian monk who was a visitor to the abbey. In the church you can see his handiwork in the figure of the risen Christ above the organ, but the Chapter Room (where the monks gather to conduct abbey business) contains what I think is his most impressive work. Nearly every surface is covered in some sort of symbolic design, including brightly colored images of creation on the ceiling and walls and stained glass windows illustrating monastic virtues. There’s a little bit of everything in this room, including paintings of the twelve signs of the zodiac. The entire effect is a bit hallucinatory, to be honest, but in a good sort of way. Take a look, for example, at this image from the ceiling:

And I love this painting of angels bearing a crown, which is also on the ceiling:

Don’t you think those angels would distract the monks from business matters?

The self-guided tour next led us to a library, bookstore and gift shop, all beautifully designed and appointed. The more time we spent there, the more the entire complex felt like a self-sustaining village, complete unto itself.

There’s one more site to visit if you happen to make your way to Saint Meinrad. A short drive from the archabbey is the Monte Cassino Shrine, a chapel that honors the Virgin Mary. In the early years of Saint Meinrad, its monks and students would take hikes to this scenic spot atop a wooded hill, which they named Monte Cassino after the Italian abbey where St. Benedict had founded European monasticism in the sixth century. In 1857 a small shrine of the Virgin Mary was placed on an oak tree there. The modest marker drew a growing stream of visitors, from farmers and soldiers to people who happened to be traveling by. A permanent chapel was built from locally quarried sandstone. Dedicated in 1870, it features a hand-carved wooden statue of the Virgin and Child from Switzerland above the altar.

As I reflect on my visit to Saint Meinrad, I realize that it’s not so strange to find this monastery in such an out-of-the-way location. Religious houses in many traditions are often located in remote places. Far removed from the busyness of the larger world, they can concentrate on matters of the spirit. It’s important as well that pilgrims have to make real effort to get to such places (think of all those cartoons of someone climbing to the top of a mountain to consult with a guru). What the seeker learns on the journey can be just as important as what she finds at the destination.

I’d like to go back to Saint Meinrad for a longer visit one day, as I know there’s much more to explore. But in the meantime, I’ve made those red-and-gold angels my computer’s wallpaper, as they remind me of the treasures you can find in the most unexpected of places.