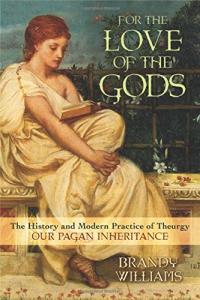

Review of For the Love of the Gods: The History and Modern Practice of Theurgy by Brandy Williams

Ms Brandy William’s For the Love of the Gods provides a rock solid foundation for crafting a personal theurgical practice. It is divided into two parts. The first part covers the origins of theurgy throughout the ancient world, where it was practiced by men and women of various ethnicities, and traces its evolution to modern times. A clever tool is to incorporate snippets of historical fiction told from a pagan perspective to give readers a “feel” for the teachers being discussed. The second part provides readers with suggestions for developing their own practice, so that “you can create relationships with the gods and love them as the ancients did. Discover how to offer devotionals, create living statues, invoke into yourself and others, and achieve personal communion so that you, too, may dwell in the happy presence of the divine.” This is accomplished largely using preexisting esoteric skills taken from whatever tradition(s) that readers have been immersed in.

Theurgy can be used to accomplish the goal of life, as summarized by Plato:

“The great teacher Plato said the true goal of a life is to become good, to center our lives not on material gain but on spiritual understanding. As our love for the gods draws us we seek to become like the gods ourselves, suffused with their light, dwelling within the happy presence of the divine.”

Ms Williams points out that practitioners of many contemporary traditions can benefit from immersion in theurgy and that their traditions evolved from ancient practices:

“The rituals we do today are rooted in Pagan Hellenistic culture. Scholar-magicians are working to re-link the rituals of the Greek Magical Papyri with the philosophical texts that describe them. We call what we are doing by the ancient word for spiritual magic: theurgy. This book presents rituals for practicing theurgists. They can be performed by Witches, Pagans and ceremonial magicians alike, because are based directly on the foundation of all our magics.”

Ms Williams argues that it was not just magick that was passed from ancient times, but that theurgy was too, through texts:

“Theurgy is a Pagan religious and magical practice that was passed from teacher to student. Although some have declared that the connection to our Pagan past was destroyed, this book links contemporary rituals with ancient teachers, reclaiming Pagan theurgic practice in the continuity of history.”

The Neoplatonic theurgist, Proclus (Proklos), promoted a well rounded approach for his students consisting of working on the body, mind and spirit all while being a good citizen:

“In Proclus, Neo-Platonic Philosophy and Science, Lucas Siorvanes outlines the curriculum. First, the student cultivated natural physical health, then civic virtue, fulfilling individual political responsibilities. Then came purifications which prepared the student for a contemplative, philosophical, life. The student contemplated physical and theological realities. Finally the student was prepared to tackle theurgy, ritual operations bringing the philosopher into union with the divine.”

Proclus (Proklos) also saw women as equal to men, which was very progressive for the time and place in which he was living:

“In her work The Academy under Proclus, Nina Ellis Frischmann lists the justifications Proklos offered for his decision. Women have souls just as men do, and share the same virtues and pursuits. Education makes women better citizens and counterbalances their natural passions. Women in other societies took leadership positions, proving this was possible. Proklos also noted the gods possessed women as well as men. Didn’t that prove women and men must share the same type of soul?”

While almost all academics publicly speak out against Pagan ritual (which includes theurgy), some of these actually practice privately:

“Although the Christian laws that prohibited the practice of Pagan ritual never succeeded in suppressing that ritual entirely, and Pagan ritual is today again practiced openly, the general prejudice against Pagan practice was reflected in academic studies of theurgy until quite recently. … Despite this official disdain, some of the academics who studied the subject also practiced theurgic meditations and even theurgic rituals. Throughout my career as an outsider scholar I have met academics who disclosed their practice to me while asking me not to reveal the fact to their colleagues, for fear of being ostracized and even losing their university positions. That situation is changing as Pagan religion moves into the mainstream. Public Pagan scholars move into the academy, academic conferences include academics and non-academic Pagans, and academic practitioners discuss their Pagan involvement more openly.”

After providing a partial list of deities used in the Greek Magical Papyri, Ms Williams argues that theurgy should be flexible and inclusive of other traditions:

“Is it possible to approach other deities than those listed here through theurgic techniques? The ancient theurgists did. Proklos added deities to his devotional list whenever he travelled. The list of deities from the papyri seems eclectic. Since this is an urban system, and a living one, there should be in theory nothing to block a theurgist from using theurgic techniques to approach deities from other pantheons than the Kemetic and Greek. For example, many Pagans who work with Hellenistic deities also work with Norse and Celtic deities.

Hinduism, Buddhism and Santeria are living religions which also honor deities with techniques similar to that of theurgy. Statues in Hindu temples are brought to life by the priesthood. Small Buddhist statues are sold for home use that have been consecrated with a similar technique to theurgic animation. Santeria practitioners invoke the orishas to possession.

Since these are living traditions, these deities should be approached with the devotionals from their traditions. Their devotees may use techniques similar to the work we are doing, but the deities have their own rituals, and we should honor them by learning them on their own terms, rather than incorporating what interests us out of context. The same is true for Native religious rituals from around the world.”

Although she has reservations about Christians practicing theurgy, Ms Williams states:

“Christian theurgists practice today. … I am personally aware of several contemporary theurgists who primarily identify as Christian.”

In order to craft a personal theurgic practice, Ms Williams states:

“We have noted that the philosophical texts are not fully understood until we engage in ritual practice. … How can we recover their rites? Fortunately texts do survive which describe religious ritual, many collected in the Greek Magical Papyri. … Also, some rituals in contemporary Witchcraft and Ceremonial Magic are specifically theurgic and have been practiced for many decades, providing us with examples which may be useful in our own practice.”

Ms Williams points out that theurgy can be grafted onto many, if not all, spiritual modalities as this paragraph on the need for protection shows:

“However it is a prudent idea to wear some sort of protective jewelry while doing this work. Witches may wear a silver pentagram, Thelemites may wear a unicursal hexagram, Pagans may wear specific stones or symbols reflecting deity.”

Similarly, she points out that elements of existing practices can be employed in crafting personal theurgic rituals:

“Witches and Ceremonial magicians have ways of creating ritual space. Witches can cast a circle. Golden Dawn magicians can do a Lesser Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram to cleanse a space. They can also do an Invoking Ritual of the Pentagram with a specific element or planet in mind. Thelemites have Crowley’s wonderful ritual of the Star Ruby which draws specifically on the entities from the Chaldean Oracles.”

It should be noted that the Chaldean Oracles were considered divine by Neoplatonic theurgists.

Regarding vegetarianism, which is of personal interest to me, she writes:

“Some contemporary theurgists are vegetarian and cite Pythagoras and other ancients who did not ate little or no meat. Each of us individually must decide what we eat and what we offer our deities, but sacrifice of live animals is not necessary to the operation. As we have seen, if you feel such a sacrifice is necessary, theurgist Aleister Crowley suggested substituting your own blood for that of a living creature.”

As stated above, For the Love of the Gods provides a rock solid foundation for crafting a personal theurgical practice. Ms Williams supplies numerous recommendations for further study which is incredibly helpful. Despite being an easy and pleasurable read, For the Love of the Gods is an intermediate level text as it presupposes a knowledge of basic magickal techniques. Those readers with such a background will find themselves on an incredible journey tapping into powerful transformative experiences.

Tony Mierzwicki

Author of Hellenismos: Practicing Greek Polytheism Today and Graeco-Egyptian Magick: Everyday Empowerment.