Having introduced the conversation and offered a few necessary clarifications, we’re now ready to start addressing some concerns about polyamory from a Christian perspective. And the strongest objections raised against polyamory have tended to be about sex. So in this post, we’ll discuss the basis for Christian ethics in general and some specifics of a sexual ethic in particular, and we’ll apply that ethic to polyamorous relationships.

Love-based ethics

I’ve frequently written on the theme of love as our only law. Jesus and the Apostles repeatedly point to love as the source for all our ethics. Christians are not supposed to be making lists of rules—dos and don’ts—to be unswervingly followed “because the Bible says so.” Instead, we’re supposed to gauge our behavior by the simple question, “Are my actions loving?” Or to put it another way, “Am I doing unto others as I would have them do unto me?”

But this can admittedly be a tricky question to answer at times. It often requires the deliberation of many factors within a given context. And that context is important because specific contexts are unique, and different contexts can require different responses.

So in the New Testament, when we see certain commands to do or not do certain actions, we should not read them as if they were meant to be rules set in stone for all time. They are specific responses given in the specific context of their time and place. They are records of the early church’s attempts to answer the question, “Are our actions loving?”

It would be incredibly irresponsible to simply lift these responses out of their contexts and apply them as one-size-fits-all rules for our day. Far from being faithful to scripture, such a blind cut-and-paste application distorts everything about what these texts stand for. Instead, we must look to them as examples. As we read them, we consider how these early Christians applied the law of love in their contexts, why that might be, and how we could apply the same principles in our own contexts. But we must avoid the temptation to turn these texts into a new list of laws.

In future posts, we will be examining a number of such texts and considering how their principles might apply to polyamorous relationships. But for now, we’ll continue on with some general principles for Christian sexual ethics.

A love-based sexual ethic

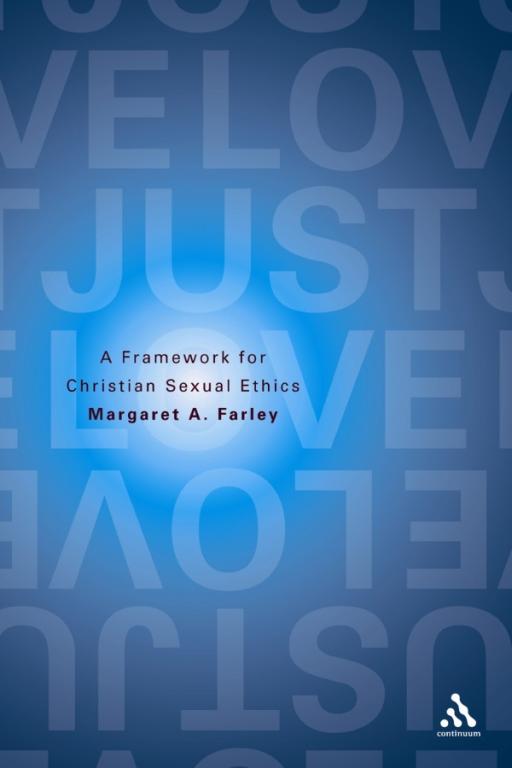

So how might the love-based ethic of Jesus apply to the realm of sexuality? I’m going to refer here to the incredible work done by Margaret A. Farley in her book, Just Love: A Framework for Christian Sexual Ethics.

As a Catholic nun, she can hardly be accused of wanting to twist scripture in order to justify her own desires (an accusation made all too often against us Christian poly folks). She is, in fact, a devout Christian and a world-class scholar who has plumbed the depths of scripture, tradition, secular disciplines, and contemporary experience (her variation on the classic Wesleyan Quadrilateral) in order to identify seven guiding principles for grounding our sexuality in love and justice.

These are not a list of rules to follow. They are simply tools to help us answer the question, “Are our actions loving?” And while I certainly wouldn’t claim infallibility for them (and she wouldn’t either), they offer the best framework I’ve seen for navigating matters of sexuality from a perspective that is neither legalistic nor Puritanical, but that is both responsible and distinctly Christian1:

- Do no unjust harm

- Free consent of partners

- Mutuality

- Equality

- Commitment

- Fruitfulness

- Social justice

Christian sexual ethics and polyamory

I haven’t the space to defend these seven principles here, and I wouldn’t be able to do them justice anyway. Read Margaret Farley’s book for yourself to see her own arguments. But I will quote a brief snippet from Farley’s explanations of each principle, and I will consider how each might apply to polyamorous relationships (as her book does not directly address this topic2).

1. Do no unjust harm

But there are many forms that harm can take — physical, psychological, spiritual, relational. It can also take the form of failure to support, to assist, to care for, to honor, in ways that are required by reason of context and relationship. … As inspirited bodies we are vulnerable to sexual exploitation, battering, rape, enslavement, and negligence regarding what we know we must do for sex to be “safe sex.” As embodied spirits we are vulnerable to deceit, betrayal, disparity in committed loves, debilitating ‘bonds’ of desire, seduction, the pain of unfulfillment. (pp. 216–217)

For this principle, polyamory is hardly different from monogamy. The same basic requirements apply to either. In polyamory, there are simply more potential partners for whom to care. Furthermore, polyamory is marked by the need for particularly open and honest communication in order to avoid deceit or betrayal as here described. That said, honesty and openness are every bit as important in monogamy—it’s just that the symptoms of dishonesty or hiddenness don’t show themselves as immediately therein.

2. Free consent of partners

This means, of course, that rape, violence, or any harmful use of power against unwilling victims is never justified. Moreover, seduction and manipulation of persons who have limited capacity for choice because of immaturity, special dependency, or loss of ordinary power, are ruled out. The requirement of free consent, then, opposes sexual harassment, pedophilia, and other instances of disrespect for persons’ capacity for, and right to, freedom of choice. (p. 219)

My fellow progressives and I talk a lot about consent. We talk about it so much that folks sometimes accuse us of reducing sexual ethics to this one factor alone. That’s not true, of course; additional factors are also important (such as the other six principles here). But consent must absolutely be at the center of any just sexual ethic. And the need for consent in polyamory is the same as in any other context.

3. Mutuality

We all know that patience, as well as trust, and perhaps unconditional love are all needed for mutuality to become what we dream it can be. But what is asked of us, demanded of us, for the mutuality of a one night stand, or of a short-term affair, or of a lifetime of committed love, differs in kind and degree. … No matter what, however, it entails some degree of mutuality in the attitudes and actions of both partners. It entails some form of activity and receptivity, giving and receiving — two sides of one shared reality on the part of and within both persons. It requires, to some degree, mutuality of desire, action, and response. (p. 222)

As with the previous two principles, the principle of mutuality applies to polyamorous relationships as much as to any others. This mutuality must simply extend to every partner one may be involved with. And on that note, it’s important that Farley points out the differences that may exist between different kinds of relationships. They will vary in the levels of mutuality needed, but all require mutuality to some degree.

4. Equality

The equality that is at stake here is equality of power. Major inequalities in social and economic status, age and maturity, professional identity, interpretations of gender roles, and so forth, can render sexual relations inappropriate and unethical primarily because they entail power inequalities — and hence, unequal vulnerability, dependence, and limitation of options. The requirement of equality, like the requirement of free consent, rules out treating a partner as property, a commodity, or an element in market exchange. (p. 223)

Questions of equality and power dynamics are certainly heightened in polyamory. The need for equality goes beyond the individual relationships and extends to to the larger polycule (or the system of connected relationships). One should not only be equally matched to each partner separately, but should also ensure some level of equality in how each separate partner is treated.

As with the principle of mutuality, levels of equality may differ from one relationship to another—so I don’t mean to speak entirely against the idea of primary and secondary relationships, for example. The precise levels of equality are something that all individuals involved must work out for themselves and find agreement on. But as a baseline, it would not be right to prioritize certain partners to point where other partners feel excluded, uncared for, or unaddressed in their feelings.

This should not be taken as an inherent problem for polyamory, but it is a reality that must be acknowledged and attended to.

5. Commitment

Rhetoric should be limited regarding commitment, however, for particular forms of commitment are themselves only means, not ends. … Even if commitment is only required in the form of a commitment not to harm one’s partner, and a commitment to free consent, mutuality, and equality (as I have described these above), it is reasonable and necessary. More than this, however, is necessary if our concerns are for the wholeness of the human person — for a way of living that is conducive to the integration of all of life’s important aspects, and for the fulfillment of sexual desire in the highest forms of friendship. (p. 226)

In my previous post, I clarified, “Polyamory involves no less commitment than monogamy; it just looks a little different. The specifics of polyamorous commitments may vary from one another, and the key is communicating well enough to understand what each given commitment should look like.” Even if a given relationship exists only for the space of a one-night stand, a baseline level of commitment, as Farley describes above, is still needed. And the deeper a relationship may be, the greater the level of commitment will also be.

6. Fruitfulness

Beyond the kind of fruitfulness that brings forth biological children, there is a kind of fruitfulness that is a measure, perhaps,of all interpersonal love. Love between persons violates relationality if it closes in upon itself and refuses to open to a wider community of persons. … But love brings new life to those who love. The new life within the relationship of those who share it may move beyond itself in countless ways: nourishing other relationships; providing goods, services, and beauty for others; informing the fruitful work lives of the partners in relation; helping to raise other people’s children; and on and on. All of these ways and more may constitute the fruit of a love for which persons in relation are responsible. (pp. 227–228 )

The principle of fruitfulness, as Farley here describes it, is one to which polyamory seems particularly predisposed. In fact, if her words were read out of context, they could easily be taken to specifically describe polyamory. The fact that Farley doesn’t actually have polyamory anywhere in view just makes the parallels that much more remarkable. Polyamory is all about opening love to a wider community of persons, rather than letting it close in upon itself. It’s all about letting relationships move beyond themselves to nourish other relationships. In every way, polyamory exemplifies this principle of fruitfulness.

7. Social justice

Whether persons are single or married, gay or straight, bisexual or ambiguously gendered, old or young, abled or challenged in the ordinary forms of sexual expression, they have claims to respect from the Christian community as well as the wider society. These are claims to freedom from unjust harm, equal protection under the law, an equitable share in the goods and services available to others, and freedom of choice in their sexual lives — within the limits of not harming or infringing on the just claims of the concrete realities of others. Whatever the sexual status of persons, their needs for incorporation into the community, for psychic security and basic well-being, make the same claims for social cooperation among us as do those of us all. (p. 228)

For the principle of social justice, Farley really breaks it down into two distinct but related principles. The broader principle is the one outlined above. A Christian sexual ethic, Farley argues, must respect all such differing varieties of sexual expression, and it must acknowledge such persons’ needs for incorporation into the community. And this perfectly reflects what I’ve been saying regarding the need for the church to be the church for all people, including for its polyamorous members.

Farley describes the narrower principle related to social justice below:

At the very least, a form of “social justice” requires sexual partners that they take responsibility for the consequences of their love and their sexual activity — whether the consequences are pregnancy and children, violation of the claims that others may have on each of them, public health concerns, and so forth. No love, or at least no great love, is just for “the two of us,” so that even failure to share in some way beyond the two of us the fruits of love may be a failure in justice. (p. 229)

While the broader principle related to social justice seems to affirm polyamory, this narrower principle provides a necessary caution. As with the principle of equality, this is not an inherent problem for polyamory, but it is a reality that must be acknowledged and attended to. The more partners one has, the more third parties there will be. And particular attention needs to be paid to these third parties—the children come particularly to mind—to ensure that they continue to have all their needs provided. That said, while I can only speak anecdotally, for every polyamorous relationship that I’m personally aware of, the children are positively thriving. Far from their parents’ polyamory being a source of struggle for them, the children delight in having so many different loving people involved in their lives.

Conclusion

I really believe that Margaret Farley is right on track with these principles. We won’t go far wrong if we heed their advice. And as we’ve seen, polyamory is not only fully compatible with these principles, but actually exemplifies some of them better (I believe) than monogamy can. But I’m not speaking against monogamy here. Everyone is entitled to their own relationship styles, and each poses its own unique challenges and advantages. Polyamory is no better or worse than monogamy in this regard. It’s just different.

We still have more to address in this series on polyamory and the church, so stay tuned!

Footnotes

1 By “distinctly Christian,” I do not mean to imply that these principles are exclusive to the Christian faith. I imagine that most people, from any faith or lack thereof, would be in general agreement with these principles as at least a baseline for justice. I simply mean that they are distinctly aligned with a Christian view of morality.

2 The book does include a few references to polygyny and one brief reference to certain open-marriage proposals from the 1970s. However, these are not examined in great detail, and none of the objections raised against them are applicable to polyamory as a whole.

Posts on polyamory

- It’s Time for the Church to Talk About Polyamory

- Conflating Polyamory, the LGBTQ Community, and Orientation

- What Polyamory Is Not

- Christian Sexual Ethics and Polyamory

- Southern Baptist Preacher Affirms Polyamory (Interview with Rev. Dr. Jeff Hood)

- Is God Polyamorous?

- 5 Reasons for Writing about Polyamorous Families (Guest Post by Mark Kille)

- Polyamory and the Kingdom of God (by Christian Chiakulas on Radical Christian Millennial)

- What Are Polyamorous Christians to Make of Karl Barth? (Guest Post)

- Polygamy and the Problem of Patriarchy

- Forthcoming…