Exploring faith, race, and Sudanese identities in Black History Month

By Guest Author Aya Elmileik

“Where are you from?”

“I’m from Sudan.”

“Wait, from where?”

“From Sudan. In Africa. Near Egypt.”

“No way! But … you don’t look Sudanese.”

“I don’t know what to tell you, I’m definitely Sudanese.”

“Well … you just don’t look like them. You look lighter … different …”

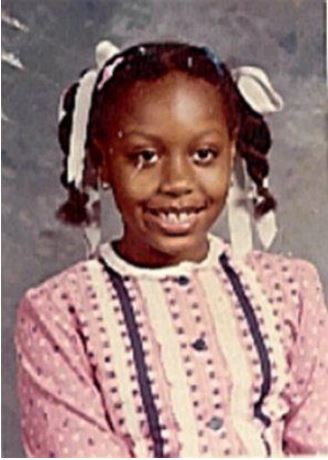

This isn’t a scenario. This is my reality. At the age of 10, my family and I moved from Japan, where we lived for 7 years, to start a new journey in the United States. I’m sure that from early on, my identity was questioned but my earliest memory would probably be when I was about 13 years old. A classmate asked me where I’m from. At the time, it was an easy question to answer, or so I thought. I’m Sudanese. Pretty simple.

Boy, was I wrong.

Living in the US, my life became a constant battle of defending and explaining my identity. People questioned my ‘Sudanese-ness’ left and right.

Common reactions I got when I answered the “where are you from” question included:

- But your skin is light

- But you look “different”

- Are you mixed with something?

- So, both of your parents are from Sudan?

- But you speak Arabic

And wait for it …

- ARE YOU SURE? (Are YOU sure you should question me about my very own identity?)

I must admit, though it may have been the most shocking reaction, for some reason, I find it to be the funniest reaction. It’s so out of this world ridiculous, I don’t know how else to react but to laugh.

In the mix of it all, I had to battle putting myself in a specific category because Sudanese just wasn’t good enough for scholarship applications, extracurricular activities, college applications, etc. Am I Black? Am I Arab? Am I African? What the hell am I?

I can identify with Black. I can identify with Arab. I can identify with African. All of these identities, however you want to mix them, to me are what it means to be Sudanese. I actually find myself pretty lucky. In college, I was able to participate and be part of a variety of clubs and organizations. The Black Student Union, the African Student Association, the Muslim Student Association, and so many more. It felt great to not have to tie myself to one specific box. These were the years I truly realized that being Sudanese is the best thing to happen to me.

As I went through my teenage years and into college, I started to realize that many Americans had a very specific image of what a Sudanese person looks. It seemed to be based mainly on news regarding the ongoing struggles in Sudan, specifically Darfur and the now newly formed nation of South Sudan.

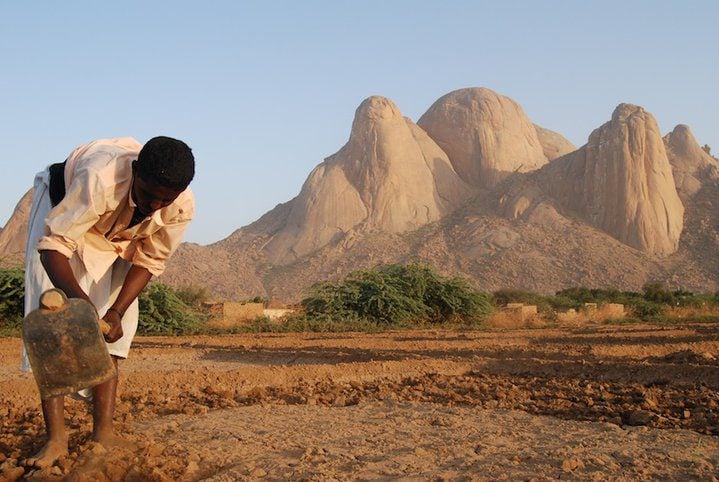

To me, however, these places are part of the Sudan I speak of. When I say I am Sudanese, I am fully acknowledging that I am part of the amazing country made up of so much diversity, including Darfur and South Sudan. The country that is made up of people with different shades of skin color, religion, dialects, tribes and cultures.

Interesting enough, because I grew up in the US, I learned that diversity is important and should be celebrated. I definitely credit my parents for this lesson, as well. We grew up having healthy debates about race within Sudan and outside of Sudan. These discussions have taught me a lot of things even I may have been ignorant to. I also realized that I can’t get angry because someone questions my identity. I learned to take the opportunity to teach them about our country and the people it’s made up of. I had to find a way to see the positive.

Learning the valuable lesson on the importance of diversity from a young age, I don’t recall a time when I consciously had an issue with anyone from any part of Sudan because we’re seen as “different” from one another. Our diversity is what makes us so unique and beautiful. I take pride in it.

In Sudan, we have our own discrimination issues within the country. I think it’s important for us in the diaspora to learn from our opportunities and lead by example in showing all people we meet in life, including Sudanese that we are better united and better when we’re celebrating and appreciating each other’s differences.

I can no longer fault someone for not knowing that Sudan is made of many different people. What I hope is that people have taken away something positive from these encounters. I hope that they are more careful with what they say. I hope that we all learn to be more compassionate and ask the right questions to help us understand each other better.

I am Sudanese.

Aya Elmileik is a Sudanese American currently with Al Jazeera English as a digital producer. Follow her on Twitter (@DiscoverAya) sharing things about Sudan and female empowerment.

Aya Elmileik is a Sudanese American currently with Al Jazeera English as a digital producer. Follow her on Twitter (@DiscoverAya) sharing things about Sudan and female empowerment.