This essay is part of the #MyMosqueMyStory Friday series

By Alia Sarfraz

If we are to confront the topic of mosques, we must first address these questions:

What’s in a name?

Growing up, we would often refer to the Muslim house of worship as a ‘mosque,’ instead of using the Arabic word masjid. It was our way to relate that we are Western and yet holding values that are Eastern and very dear to us. Using the English word was the middle ground that conveyed a mix of cultures. It was only until much later in life, that we were discouraged from using such terminology because of the mistaken belief that the English word is derived from the word “mosquito.” Whilst that is a projection of some people’s beliefs, many will argue that they do feel isolated, unwanted, or like a mosquito which consumes and dies once suckled.

To Masjid-hop or not?

I have never subscribed to one particular mosque. I have always been open to the notion of attending as many masjids as I can, whenever and wherever I may be. I will stop by a mosque based on where I am at a particular time. Some people will refer to my sort as “masjid hoppers,” especially in Ramadan. By masjid-hopping, I experience the beauty of each masjid which has its own unique code, culture and environment.

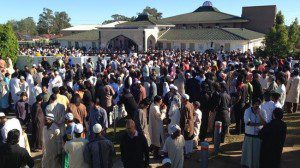

I grew up in Western Sydney, a densely and ethnically populated multicultural zone in Australia. Most of the masjids there catered specifically to each group, which meant that Arabs, Pakistanis, Turkish, Fijians, and so forth, all had separate mosques. Eid has also been separately celebrated and never under the one ‘umbrella’ which adds to the disharmony that somewhat already is in place. Communities usually end up celebrating separately. Did that mean that I was unmosqued? Yes. Absolutely. To divide masjids based upon such a premise would make it uncomfortable for a person if you did not fit into the mould of the race that was running the facility and if one was a person who attended due to convenience of location. It quickly changes from a place of worship that should be open to all into a divisive screening measure when such divisions are in place.

Having said that, I always enjoyed receiving Turkish delight whenever I would visit the Turkish mosques where my father was revered as a community elder who helped to secure land from the Australian government for the construction of the mosque in Bonnyrigg. Though he was not Turkish, he was made the head of the Turkish Council in Australia. The point is: you can become one of them if you expose yourself and hang around long enough.

One of the primary reasons for our attachment to the Turkish mosque was due to vicinity. Proximity always equalled convenience. Also, many members of the Turkish community would come seek medical treatment from my father and seek his assistance due to the local government connections he had. I know this may not be the case for most people. There was also the completion of the Turkish Islamic school project which was also close by; leading to the a Turks having a greater stronghold within our local area.

Closer towards the city, the ethnic groups would change. The Lebanese had greater control over Lakemba. Fijian Indians had their own masjid also closer to home, but this wasn’t established until much later. For some reason, the Turks seemed to have greater standing. This was partly due to them being greater in population, unity, more goal-oriented and having more funding. What’s more, if a masjid also had the traditional appearance of a minaret and a slender tower with balconies, it seemed as though people would take those houses of worship more seriously than the homes that were converted into masjids like the one owned by the Fijian community. Generally, I find that mosques that are converted old homes have a more pleasant and welcoming vibe as they are less austere in their architecture.

The Gender Question

My mosque adventures were almost always made with my father when I was a child. My mother hardly ever ventured into a masjid, as from a cultural perspective, as women never attended masjids in Pakistan. In fact, many masjids there don’t even have a women’s prayer area. ‘Ibadat,‘ or worship was meant to be done at home. This is the conventional understanding which gives rise to the notion that a woman’s contact with the masjid may not necessarily lie in her interest. Most ‘respectful’ women observe their prayers at home for that reason. What’s more was the prevailing belief that to venture out of the home without a mahram, even if for the purpose of prayer, is what only attention-seeking females do. Jumah prayers for women are not compulsory and can be done at one’s abode, as well. Besides, the reward to be reaped was higher at home.

Since it is not mandatory, it was never imposed nor common practice for my mother or many women who hail from overseas where a woman’s role in worship and personal duties mainly revolve around the home. It must be noted that my own mosque attendances stopped as I grew older. More specifically, when I hit puberty. Clearly, my mother’s cultural experience somewhat jaded me and my understanding of what a masjid’s role was and where women stood in light of that.

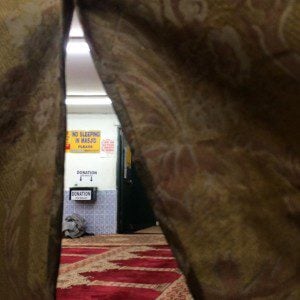

Hitting puberty is awkward enough. It becomes more delicate, thorny and troublesome when Muslim males and females become conscious of the changes and the way they interact with people of the other gender. When I was younger I was able to go back and forth between the men and women’s area in a masjid and no one ever had issues. Upon being scolded or hearing my father also being advised not to bring me there anymore, I felt like my presence wasn’t wanted. I took it to heart and things changed drastically. As I grew older, my mother made very infrequent appearances at the masjid and it was more ‘appropriate’ for me to be in the women’s section which was segregated and often in the back. It was always the smaller portion, more secluded with an almost prison-like vibe. Not welcoming at all. My memories of going to the masjid at this point in my life is a blur, because it was a rarity. My more positive memories were of those when I was young, free to roam and even able to play with friends there. Only if there was a death of someone in the community or if it was Eid prayers would my mother and I even consider going to a masjid.

As a result, masjids started to appear daunting and isolating to me. Even though we were never told this, it was understood that even if a woman never covers outside the mosque premises that she would do so upon entering a mosque out of respect. Her eyes would need to be veered towards the ground and her voice never elevated. Masjids are never places where one ventures to have fun or socialize. You pray, say your salaams and exit. The men entered from the front door; you as a woman are to enter from the back which was far, far away from the car parking space. Rules of moderate dressing applied to both men and women.

The definition of moderate and the interpretation of dress codes varies from person to person. When it came to women: to some it means no pants allowed whatsoever and that the dress had to be ‘feminine’ and not ‘masculine’. To others it means wearing no nail polish. I guess the head should ALWAYS be covered. Even non Muslim celebrities are told to adorn the scarf if ever they enter the realm of a masjid as a sign of respect. Men typically have given me these looks as though to say, “Why are you even here?” This pretty much was the tone of most of the mosques I have come across, be they in America, Australia, Pakistan or Saudi. The presence of women is either unexpected and if made is normally with their ‘mahram.’ In the Kaaba, men and women pray side by side and this never occurs anywhere else. It seems almost revolutionary and yet it isn’t.

Are We Standing Alone?

I attended a Methodist , girls-only high school. We used to attend chapel, assemblies and even visit other houses of worship as part of the curriculum. Even though we sat on chairs as part of the process and never had to take our shoes off, I still felt a lack of connection. I was always reassured during these sessions that my faith was the one for me. I was being told Jesus died for me and my sins every day and yet it never took me to the elevated states that I felt in completing sujood and asking for forgiveness from my Lord directly. There is something special at least for me when I cover, prostrate, humble myself in taking shoes off and cleanse myself with water and by sitting on the ground.

Not being white or growing up in a Christian family made me feel somewhat out of place at school. Whilst certain aspects disengage me from community, I am able to re-engage and be uplifted in a mosque. No amount of carol singing, hymns and being preached to would change me. My own act of prayer meant more to me. When I visited synagogues, I noted that there is also gender segregation. We were told that men and women were to sit in different sides of the hall and women had to cover so as not to distract men by their beauty. So, in some ways the principles were similar to my own faith. Suddenly, my mosque experience didn’t feel so lonely. I realized that women can be deprived of the rights and character of their religion in other houses of worship aside from the mosque. Many houses of worship can be isolating and the mosque is not alone.

What About The Kids?

I am now a mother, and the masjid environment has not changed much from my own youth, in my opinion. The feeling of oneness and wanting to belong to a masjid is there, but women are still not always welcome. Also, there are the ‘hijab police’ who feel free to offer their opinions towards my children who aren’t even of the age of covering yet. I live in America now and many mosques here have an even more fundamentalist vibe to them. I have been told that my four year old child should be covered and wear fully covered leggings as they served as to great a distraction and prevent people on focusing on the purpose of prayer. My kids aren’t as able to roam in a masjid as I did when I was a kid. I am also scared to let them out of my sight after hearing about sexual misconduct allegations which occurred in a local mosque. The reality is that the shaitaan can enter anywhere at any given time.

What About the Elderly?

Now as I have become an adult and mother, I do from time to time encourage my own mother to attend the mosque. However, for the elderly, having an upstairs gallery (where many mosques place women) isn’t necessarily the most practical idea. It is difficult for her to access masjids with huge staircases inside and outside the masjid. Elderly men don’t have this issue, as usually the men’s prayer space is on ground floor. It also is harder for elderly people to sit on the floor and walk all the way to the back. Assistance from the youth is often required in finding a chair to sit on as well. Wheelchair access is only afforded in some masjids. Elevators have been present in some masjids but this is a rare occurrence. Women of all ages and abilities face obstacles at the masjid.

Can We Move Forward?

The unmosqued movement arose because people were feeling disconnected from the faith while in the mosque. In my opinion, mosque architecture, paintings, furnishings, supplies and other needs be reconsidered and made more ‘user friendly.’ While they are becoming more luxurious, the atmosphere may not be conducive to every member of the community feeling at home. The tone of Imams in their speech should be considerate and the sermons they deliver should also be relevant and not drive away the audience. Today, funds are also there now for projects which were not available to many of the first generation of Muslims that went abroad. Accessibility – for all – is key.

I have been living outside of Australia for more than ten years now and am sure that the ‘masjid scene’ there has changed dramatically and that my accounts have become of the past. I will say this: there is a revival of the mosque. They are more utilized than they used to be by first generation Muslims who went abroad. In fact, they are the most liveliest and bring the spirit of Ramadan best when they offer Iftars and salat in the last ten days of the holy month. Things are changing. The socialization of community is often becoming more centered around masjids.

We need more open and engaging houses of worship where women and minorities are not second-class citizens in the masjid. This would set the tone for how women are treated at home by many Muslim men as well. The status quo is not what our Prophet (SAW) would have wanted. Nor should we want that. Reform will happen and is occurring through dialogue. Alhamdulillah.

Alia Sarfraz hails from Australia and is now based in the USA. She considers herself to be a global citizen as her parents are originally from Pakistan. She is a mother to two children and knows that standing up to injustice is where her heart truly lies. Visit her personal blog where she addresses issues such as racism and the hypersexualization of women of color and misogyny and cultural practices.

Alia Sarfraz hails from Australia and is now based in the USA. She considers herself to be a global citizen as her parents are originally from Pakistan. She is a mother to two children and knows that standing up to injustice is where her heart truly lies. Visit her personal blog where she addresses issues such as racism and the hypersexualization of women of color and misogyny and cultural practices.