I had a good education. It could have been better, but that’s through nobody’s fault but my own. I mostly rushed through assignments for good enough. I read to answer the necessary questions. And if I didn’t need to finish the book, I wouldn’t. Eventually, I came to appreciate a good book, a challenging piece of writing, art, and even poetry. In fact, I’ve really come to enjoy poetry, surprisingly so. Almost like a kid that has learned enough words of a foreign language to string together a sentence. It’s exciting. It’s new. It’s pretty rudimentary. It’s amateur poetry corner.

I can’t pretend to have any expertise on what makes a good poem, but I trust others who have some good suggestions, and I know what I like. This amateur poetry corner is a layman’s venture into looking at some poems. The first of which is: The Horses. (It’s not too long, and definitely worth a read).

Bonus: For those of you who are wondering if (in the vein of a previous post) I have an obscure early 2000s vaguely related post-apocalyptic indie-folk song recommendation to accompany this poem–I, in fact, do: Peter and the Wolf’s–The Fall).

A Post-Apocalyptic Poem with Hope

Edwin Muir wrote The Horses in 1956, published in One Foot in Eden. He was looking at a world of potential nuclear fallout, barely having recovered from World War II. The Horses vaguely alludes to an all-out war, scorched earth, and minimal survivors. Your imagination can fill in the details, which is one reason I think the poem still works so well now, but the scraps of the recent history of the poem build towards a future, even with a hint of hope. Though I’ve written about hope before, this explores a new dimension of hope.

If on the stroke of noon a voice should speak,

We would not listen, we would not let it bring

That old bad world that swallowed its children quick

At one great gulp. We would not have it again.

Sometimes we think of the nations lying asleep,

Curled blindly in impenetrable sorrow,

And then the thought confounds us with its strangeness.

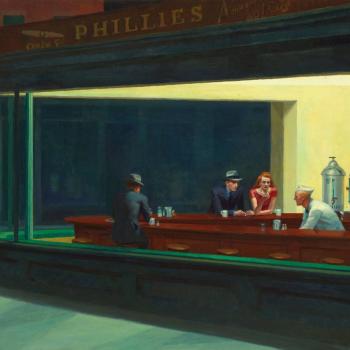

The tractors lie about our fields; at evening

They look like dank sea-monsters couched and waiting.

We leave them where they are and let them rust:

“They’ll molder away and be like other loam.”

We make our oxen drag our rusty plows,

Long laid aside. We have gone back

Far past our fathers’ land.

And then, that evening

Late in the summer the strange horses came.

Seeing More Clearly

The horses return to man, as man returns to the land, and returns to the simplicity of life to find some sliver of goodness that is illuminated in the best post-apocalyptic tales (e.g. Cormac McCarthy’s The Road). Man can look around after (or during) these moments of suffering or loss, and can often see the proper value and meaning of things more clearly. In many ways, the fear of not having darkens what we have; we lose it even. The horses, there all along, are seen as a beacon of life to come. The horses are a sort of recognition of what is already there, though long neglected. A deepening of life in the reality that already exists.

G.K. Chesterton’s short work, The Crimes of England, is subtitled: “There are two ways to get enough. One is to continue to accumulate more and more. The other is to desire less.” In this WWI era work, Chesterton sees this as ultimately manifesting as nations positioning against nations. Chesterton, who lived life to the full, is not calling for a muted heart, but to stop trying to fill a restless heart with things that can never satisfy it. While he is referring to international relations and conflicts in this work; it is nevertheless relatable at the individual level–the devastating effect that the fear of not having or losing can have on the good that is already there. There is the more satisfying pursuit of the heart into what is already here and given.

Among them were some half a dozen colts

Dropped in some wilderness of the broken world,

Yet new as if they had come from their own Eden.

Since then they have pulled our plows and borne our loads,

But that free servitude still can pierce our hearts.

Our life is changed; their coming our beginning.

Dreaful Circumstances and the Goodness of Life

There’s no advocating for a nomad-like return to pre-history, but there is something that hints at the fact that is often more evident when life is stripped down and simplified: life in itself is good. Even in a situation in which everything the world once knew, good and bad, life again unveils itself as fundamentally good. There is great hope in this notion repeated in good literature and human history. I can spend a morning reading through news stories and find a thousand dire problems in the world, down to my own community even. And to be sure, I hope we find solutions! However, underneath all of these concerns and fears, there is still an undercurrent that says even if these things should persist, life will still reveal itself as good.

Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, recalls the psychiatrist’s time in the horrors of Nazi concentration camps, specifically on the power of finding meaning and purpose even in the most dire of circumstances. Frankl insists, “Life is never made unbearable by circumstances, but only by lack of meaning and purpose.” The Horses addresses the aftermath of a horrible circumstance and tremendous suffering (war). In any given era or even life, the suffering produced by the myriad of events and circumstances is very real and does not need to be sought out. However, the crippling effect of despair and dread of what may come robs us of the memory and hope of life as good. That in all circumstances, a careful look at reality reveals some meaning and purpose, and that living life is a good thing.

In Hope We Are Saved

Frankl notes, “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.” Any given news cycle, a challenging season of life, irrational or rational fear, period of suffering, and so on, has the possibility of being infiltrated by hope. Part of the difficulty of hope is that in the face of trials and tribulations, we don’t know how the goodness will come or what it will look like. It’s patient trust, ultimately in eternal life, but in the anticipation of what’s to come in the here and now. St. Paul reminds us similarly, “For in this hope we were saved. Now hope that is seen is not hope. For who hopes for what he sees? But if we hope for what we do not see, we wait for it with patience” (Romans 8:24-25). Hope recognizes the goodness that comes anew in each new circumstance. The new beginning those horses bring is an old reminder of the goodness of life found simply in living.