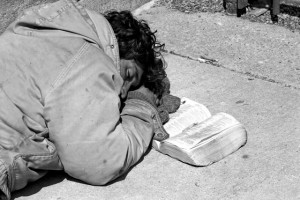

What better time than Advent to ponder what poverty means? After all, Christ became poor for our sakes, emptying himself of his divinity as he emptied himself into our humanity.

What better time than Advent to ponder what poverty means? After all, Christ became poor for our sakes, emptying himself of his divinity as he emptied himself into our humanity.

So what does poverty mean? Here are some dictionary definitions:

Poverty (Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary):

1a: the state of one who lacks a usual or socially acceptable amount of money or material possessions; b: renunciation as a member of a religious order of the right as an individual to own property; 2: scarcity, dearth 3a: debility due to malnutrition; b: lack of fertility (of the soil).

Poverty (Oxford English Dictionary):

from French pauvreté, pauper. The quality or condition of being poor.

I. The condition of having little or no wealth or material possessions; indigence, destitution, want. b. fig. in allusion to Matt. 5:3. ME: c. Personified and applied to a person in whom it is exemplified.

(I think of St. Francis’s Lady Poverty, though she isn’t mentioned here.)

II. 1. Deficiency, dearth, scarcity; smallness of amount. late ME. 2. Deficiency in the proper or desired quality; inferiority, meanness. late ME. 3. Deficiency in some property, quality or ingredient; (of soil, etc.) unproductiveness, late ME. 4. Poor condition of body; leanness or feebleness resulting from insufficient nourishment, 1523.

From these definitions, poverty seems a bad thing, a poor thing. It’s a lack, a dearth, a scarcity, a deficiency. Who would possibly seek it?

And yet, as the OED reminds us, there’s Matthew 5:3: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for the kingdom of heaven is theirs.” A friend of mine who’s a pastor once helped me see this puzzling beatitude in a new way: “Blessed are those who know their need of God.”

So is poverty a burden or a blessing?

For me, the most helpful musing on this question is Betsy Sholl’s poem “Making Dinner I Think about Poverty” in the Fall, 2014 issue of Image (#82).

The poem’s speaker is chopping vegetables at a soup kitchen; she could be in my own church basement with the volunteers there. She’s meditating on the poverty that is spiritual with a perfect image:

…the kind saints praise and scripture

calls blessed, the kind that inherits heaven

where maybe what’s left of us will be

more like a clear broth, than the vegetables

and meat we chop here…

Meanwhile, as she chops, the soup kitchen gradually fills with the poor: those who live in a physical poverty (lack of material possessions) that they have not chosen. Yet the poet’s meditation remains with the spiritually poor:

Everything with its secret heart,

Saint Francis says, where it’s better to be

prey than predator…

Poverty, he says, a word so pure

it can’t be hyped, it sees into the dark

vessels of the heart, where the blessed know

what they lose…

And the blessed, those who choose spiritual poverty, who choose to be prey rather than predator, what do they lose?

They willingly give up worldly power. They willingly give up trying to control their own lives and that of others. They lose worldly “goods”—but look at this marvelous image that Betsy Sholl offers:

what they lose, what sinks to the bottom

enriches the stock—

So, they don’t really “lose” anything! It sinks to the bottom of the pot, “enriching the stock.” I’m reading “the stock” here as a pun: the soup stock, but also the stock of humankind. That is, while the saints are left as the “clear broth” evoked at the poem’s start, what they lose—all the vegetables that she’s chopping and throwing into the pot, this nourishment which sinks to the bottom—enriches all the rest of us.

enriches the stock—which we will ladle out

to those shuffling in with their empty bowls

The soup kitchen guests are doubly nourished by this soup: their bodies are fed, but also—the poem goes on to imply—their spirits:

as if they follow the saint’s hard recipe,

the one that says: Put everything in the pot

and let fire take over.

This fire is a purifying fire. The fire that purges the heart. The fire that, in Flannery O’Connor’s stories, burns away our sins. It’s a painful fire; that’s why Sholl calls it a “hard” recipe.

Possibly, the soup kitchen guests are more open to following this hard recipe than those of us with materially comfortable lives and apparent security. I don’t want to sentimentalize material poverty, and the poem certainly doesn’t. But the loss of material things, the loss of comforts and security, might possibly give the losers a head start on gaining Matthew 5:3.

What I mean is: if you need everything, then you are perhaps more likely to know your need of God. And this knowledge is the spiritual poverty that Jesus blesses: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for the kingdom of heaven is theirs.”

Peggy Rosenthal is director of Poetry Retreats and writes widely on poetry as a spiritual resource. Her books include Praying through Poetry: Hope for Violent Times (Franciscan Media), and The Poets’ Jesus (Oxford). See Amazon for full list. She also teaches an online course, “Poetry as a Spiritual Practice,” through Image’s Glen Online program.