M emory, of both the best and the worst, is central to guidance. Without it, we forego paths that have led to prosperity, take paths that have led to ruin.

emory, of both the best and the worst, is central to guidance. Without it, we forego paths that have led to prosperity, take paths that have led to ruin.

Further, memory is extremely personal, while at the same time supremely collective. We all have our own particular catalog of recollections, which we consult, as need be. But we are all also part of a greater story, and our lives intersect with each other in such complex and dangerous ways that the shared memory of what we have been to each other, and done to each other, must be sounded to direct how we are to live with each other. This we call history, and its caretaking is a solemn affair.

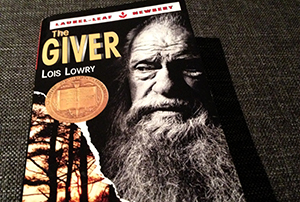

In Lois Lowry’s classic young adult novel, The Giver, brought to the screen August 15 in a very fine film version (with Jeff Bridges, Meryl Streep, and Brenton Thwaites), memory is not allowed to the individual members of the state. It is the repository of only one, who retains the past in case it’s ever needed. As he ages, he must pass—“give”—his storehouse to another.

The reason for this state of affairs is that in hopes of ridding the world of misery, the society has decided simply to stop remembering it altogether. That can only be accomplished by stopping all that would bring misery to be. The implication is that the world as we know it consists of highs and lows, peaks and valleys, heavens and hells. As such, it is a world of chance—one in which we have the power to make paradise or perdition. That is what a world is.

In defiance of that fact, in The Giver, the choice has been made to end all choice. For the argument goes that when the individual is left to his own devices—ignorant, greedy, lustful, lazy, wrath-prone wretch that he is—he will most often choose wrongly. Better to parcel out what he really needs—what he isn’t smart enough to know he does.

This will necessarily require a certain amount of surrender. If you take away the bottom, you’re going to have to take away the top. To end agony, you must also end ecstasy. The human condition is such that the possibility of the good is dependent upon the risk of the bad; the dimensions of life only rise into fullness when all things are potentialities.

In Jacques Barzun’s From Dawn to Decadence, he writes about this; the repeated historical impulse to achieve “sameness,” the elimination of degrees. It is the “leveling instinct,” which would pull up the lowly by way of pulling down the high.

What drives this impulse?—the idea that misery, which we dread, is a consequence of the conflict over differences. If all is equal, down will go sickness, crime, poverty, loneliness. So rules are made against them; committees, formed; initiatives, funded. Overseers—deputized, empowered—craft strategies to bring it all about.

But that means that individuality must go, and initiative, and competition—because they only cause conflict. And you have to take away risk and profit because such possibilities allow for loss and devastation. Along the same lines, the best way to stop envy is to sand away beauty; the most thorough means to end sadness is by way of ending its opposite, joy. One is not sad if he has no concept of bliss.

Now, these things can only be experienced in particular manifestations of the lived world—through music, poetry, art, love-making, friendship, family. Consequently, these realities must be modified—clipped in some way, trimmed so that they actualize the good of all. In the course of so doing, they become unrecognizable.

Further, not everyone can enjoy what is actualized. In a finite world, only so much can go around. So the unfit, the surplus, must give way to those deemed worthy, according to the overseer’s lights. It is ironic, that the age-old drive for egalitarianism ends in the persecution of the truly low—those who “drain” resources.

Like others before her, Lowry knows that the way to control what is felt is to control how it is talked about. In The Giver, death penalties, infanticide, and euthanasia are called “release.” Of course, words lose meaning when there is no contrast. If we eliminate degrees, we begin to lose the concepts of heat and cold, and finally, through disuse, the ability to distinguish them. For what is there to feel in such a place?

As reassurance, the state stresses that this is all part of the bargain. Fear is being eliminated, after all—the Benthamite “Leviathan,” vanquished.

It is all very tempting; it is certainly the most persuasive argument politically: “Choose me,” comfort the overseers, “and I will eliminate all that snarls your name from the shadows, all that claws at your door, that drives you from sleep in screams. Give me your freedom, and I will give you your peace.”

The problem, as the movie shows, is that such a thing cannot be achieved in a world that allows for color, or emotion, or ties that permit anything beyond a state-sanctioned level of “enjoyment.” Certainly not love. But then, enjoyment is not love.

The lesson of The Giver is that while the individual man often chooses wrongly, he is no man at all if he cannot choose, and it is no world at all if the hazard of both victory and defeat are not possibilities. The solution is for each man to choose better, not for a group of men to eliminate the option—not even with the best of intentions.

When they try, they only end up enforcing, with ruthless, monstrous precision, an ideal state that defies any semblance of what an organic polity is meant to be. Without freedom, there is no meaning, and without meaning, there is no point. Call it what they will, it is not a world; it is not a life; they are not men.

A.G. Harmon teaches Shakespeare, Law and Literature, Jurisprudence, and Writing at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. His novel, A House All Stilled,won the 2001 Peter Taylor Prize for the Novel.