To celebrate Image’s twenty-fifth anniversary we are posting a series of essays from people who have encountered our programs over the years. Read the other installments, Stumbling into the Waterfall and The Notecards of Paradise.

Guest post

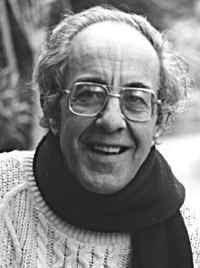

By Dan Wakefield

I was happy to be asked to speak at the first Image conference in Berkeley in 1992 and delighted to learn that Henri Nouwen, the Roman Catholic priest and Dutch theologian, would be there to deliver the Sunday homily.

My minister at King’s Chapel in Boston had introduced me to his work when he gave me Nouwen’s book Reaching Out: Three Movements in The Spiritual Life, and a friend introduced me to Henri himself when he was at Harvard Divinity School in 1983.

I had gone with a group of friends from King’s Chapel to hear Father Nouwen give a public lecture at Harvard in 1982, where the Divinity School had scheduled him in a room that held about a hundred people, which meant that another hundred or so had to be turned away. We learned later that some of the Divinity faculty were piqued that Nouwen had drawn such a big crowd—we were condescendingly described as “people from the suburbs,” i.e. non-academics, and Nouwen was whispered to be “popular,” a mortal sin in elitist theology.

The only speaker I have ever heard to match the power of Nouwen was James Baldwin, a street corner preacher as a boy in Harlem before becoming a writer. Nouwen spoke with a slight lisp, and his whole body seemed to bend forward with his hands sometimes “reaching out” in a physical effort to get across his message, not histrionically but with a passion to communicate, as if he were trying to implant his words in the hearts of his listeners.

I walked to the service at the Image conference with Suzanne Wolfe and as we walked up the steps of the chapel I asked if she had heard Father Nouwen speak before. She said she had not, and I predicted she was in for a memorable experience. After the service, I asked her what she thought of his homily. She stopped for a moment, and said “He takes no prisoners.” That was the best summation I have heard of Nouwen’s power as a speaker.

It was not from a pulpit, however, but at a dinner table, that I heard Nouwen’s most impassioned and transformative words. There was a dinner on the Saturday night of the conference for some of the speakers and guests at a private home, and I was fortunate to be seated next to Henri. The conversation at the table was polite, “spiritual-intellectual” dialogue of a perfectly pleasant sort that would neither offend nor challenge nor inspire anyone present. I could see that Nouwen was bored.

The woman at the head of the table, to my left, was telling someone that she used to be a Catholic but she had left the church because of its politics, and suddenly Henri came awake and alive.

“Forget about the politics,” Henri said. “All that is distraction. I don’t mean to denigrate or even dismiss your points but those are beside the point. The only thing that really matters is your relationship with Jesus—I mean your personal relationship with the mystical Jesus.”

The woman was taken aback, and looked perplexed. Imagining what she might be feeling, I asked Nouwen the question that I wanted to know the answer to myself.

“How does someone have a ‘a personal relationship with the mystical Jesus?’”

Nouwen leaned across the table toward the woman and said with an urgent passion, “Just give me ten minutes a day—no, five minutes! Just take five minutes a day, every day for two weeks, to sit quietly and ask to be with Jesus, ask for his presence. Then come and tell me what’s important.”

Nouwen pushed his unfinished plate aside as if to clear away any obstacles to his message to the lapsed Catholic, to focus even more fully on his response. His delivery was so intense I imagined a kind of beam going out from him to the woman as he spoke.

“People complain about The Church,” Nouwen said.” They say The Church isn’t interested in their problems. I spoke to a young man with AIDS the other day, who said to me “The Church doesn’t care about me. Where is The Church in my life now when I’m dying of AIDS?”

“I said to him ‘Who do you think I am? Who do you think any priest is? I am The Church and I care about you. That’s why I’m here with you now.’”

In that fancy dining room in that wealthy home, I felt I was in the presence of the Spirit.

In his homily the next morning he spoke of being the resident pastor at Daybreak, in Toronto, one of the “L’Arche” communities founded by Jean Vanier, where functioning adults live with people who would otherwise have to be sent to mental institutions.

Nouwen felt more comfortable there than he had at Harvard, which he left after two years of his five year contract. At Daybreak he bathed, fed, and took care of a man who was not capable of doing those things for himself.

“There is a man who lives in my community,” he said, “who asks me ‘What are you doing here?’ whenever I see him, and a woman who always smiles at me and says ‘Welcome.’ I could see these people as ‘mentally handicapped,’ or I could see them as angels who are giving me important messages every day—asking myself what I’m doing here with my life on earth, and reminding me I am welcome here.”

Sometimes in the continuing struggles and challenges of life, when I am feeling overwhelmed and drained, I remember Henri’s message at the dinner table that night at the Image conference, and I make myself stop and follow Henri’s advice.

Though I pray in some form or other every day I had not for a while thought of doing what Henri had asked—no words, simply sitting quietly and asking to be in the presence of Jesus. I did that yesterday, and I felt a great peace. I thought again of Henri, with gratitude, and looked up a favorite passage in Reaching Out.

“What if the events of our history are molding us as a sculptor molds his clay, and it is only in a careful obedience to his molding hands that we can discover our real vocation and become mature people? What if all the unexpected interruptions are in fact invitations to give up old-fashioned and outmoded styles of living and are opening up new unexplored areas of experience? And finally, what if our histories do not prove to be a blind impersonal sequence of events over which we have no control, but rather reveal to us a guiding hand pointing to a personal encounter in which all our hopes and aspirations will reach their fulfillment? Then our life would indeed be different, because then fate becomes opportunity, wounds a warning, and paralysis an invitation to search for deeper sources of vitality.”

Dan Wakefield’s memoirs include Returning: A Spiritual Journey. He recently edited and wrote the introduction for Kurt Vonnegut Letters, and If This Isn’t Nice, What Is?: Vonnegut’s Advice to the Young.