The late, great Seamus Heaney understood the sadness of the Irish landscape. He was a poet of bogs, reeds, wells, dripping things, and “mossy places.” He deliberately contrasted his native environment with more fiery regions: “We have no prairies / To slice a big sun at evening.” Instead, in the bog, “The wet centre is bottomless.”

For those whose knowledge of Irish culture is based on Bing Crosby songs, casting such a “grey eye” on Ireland might seem excessively morose. What happened to the carefree little characters of the Emerald Isle and their smiling eyes?

Heaney’s work is a truer expression of the atmosphere of the island and people of Ireland. Yes, there are glorious exceptions to the sorrowful mysteries of the Irish landscape—bright fuchsia in a dark green hedge, shocking white bog-cotton on a dirty bed of turf—but these are exceptions to the rule of lachrymosity.

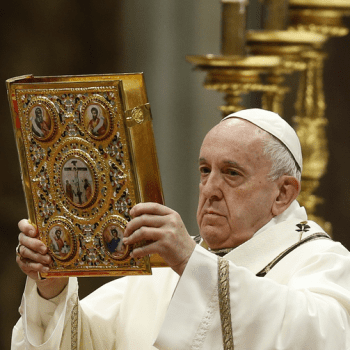

And all this despite the fact that the Irish people are (or have been) a Christian people. For 1500 years, the saving events of Christ’s passion, death, and resurrection have been central to the Irish story, so why is our mood so dark? Are our tearful tendencies simply unredeemed? Is our Christianity just a patina of orthodoxy on a solid mass of fatalistic paganism?

I certainly don’t think so: Irish Christianity has always been solidly orthodox in belief, but it can’t be denied that, emotionally, it leans more toward Good Friday than Easter Sunday.

When we discern darkness in Heaney’s poetry, then, I don’t think we should automatically catalog his poetry as non-Christian, as if Christians were only allowed to rejoice.

In Heaney’s case though, things are complicated by his expressed lack of faith. Here he speaks of early experiences on pilgrimage to Lough Derg:

[Receiving communion] was phenomenally refreshing and, when I began to admit to myself that I was losing faith in it, I was very sorry. Intellectually speaking, the loss of faith occurred offstage, there was never a scene where I had it out with myself or with another. But the potency of these words remains for me, they retain an undying tremor and draw; I cannot disavow them. Nor can I make the act of faith.

For a lapsed Catholic poet, we might expect the darker side of the Paschal mystery to predominate over the glory of the resurrection, and especially so for a lapsed Irish Catholic poet.

And yet, as I read through Heaney’s poems after his death, I found little that was immediately reminiscent of the cross. Direct reporting of violence is very rare in Heaney’s work, despite the violent events that surrounded him in the Troubles of Northern Ireland.

In “Westering,” the poet describes a Good Friday scene (“congregation bent / To the studded crucifix”) but he prefaces his description with the telling phrase: “We drove by.”

Similarly indirect is the “cross-vigil” position of the saint in “St Kevin and the Blackbird”: “The saint is kneeling, arms stretched out, inside / His cell.” In “Requiem for the Croppies,” revolutionaries die on a hill that is reminiscent of another: “The hillside blushed, soaked in our broken wave.”

Other than these oblique glances, there is little of Calvary in his poetry. This absence is all the more significant given the immense role played by Passion scenes in Irish devotion, poetry, and preaching from the earliest times.

So if Heaney’s imaginative world is neither transformed by the glory of the resurrection nor fixed on Calvary, is it better to see his work as post-Christian or, perhaps, para-Christian?

This seems to be how Heaney saw things. In a book-length interview he describes book VI of Virgil’s Aeneid (the descent into the underworld) as “a constant presence” and in the final interview before his death he proposed the underworld journeys in Homer and Virgil as more satisfying than the “contentious and exhausted” Christian myth.

This explains, at least, why his poetry abounds with bodies and “shades” (he often used this last word, capturing the double sense of Virgil’s “umbra”). For example, one of Heaney’s earliest and best-loved poems, “Mid-Term Break,” centers on the corpse of his little brother, “wearing a poppy bruise on his left temple”.

In other works he encounters murder victims, including his cousin who appears like Virgil’s Hector with wounds intact: “[I] gather up cold handfuls of the dew / To wash you, cousin. I dab you clean with moss / Fine as the drizzle out of a low cloud.”

And of course, there are the bog bodies in Ireland and Denmark which inspired poems like “The Tollund Man,” “Bog Queen,” and “Grauballe Man.”

But I find it fascinating that Heaney is so interested in preserved corpses. His bodies are not decaying. In the case of the Tollund Man, Heaney describes the preservative action of bog acid: “Those dark juices working / Him to a saint’s kept body.” Why a saint’s body?

Likewise, the Bog Queen lies “waiting” in her bog. Waiting for what? Does her archaeological resurrection (“I rose from the dark”) figure another awaited resurrection? The Grauballe Man, too, presents a certain defiance of death: “Who will say ‘corpse’ / to his vivid cast?”

Heaney may have set Christian myth aside, at least consciously, but still I think it is valuable to read his poetry in the light of the Paschal mystery. He is not a Good Friday poet, peering at the passion. Nor is he an Easter Sunday poet, seeing creation already made new.

He is instead a Holy Saturday poet, a poet of weeping and waiting, a poet between crisis and consummation. And if Christ’s body is the kernel of wheat which has died, Heaney’s corpses too hold tiny grains of hope: “winter seeds” in the Tollund Man’s stomach, barley in the croppies’ pockets. This poet’s Triduum is interrupted but not, I think, definitively.

Brother Conor McDonough, OP, is a student friar in the Irish Province of Dominicans. He is from Galway and studied at King’s College, Cambridge.