“Life imitates art far more than art imitates life.” Oscar Wilde’s mischievously challenging line appears across the opening frame of a film about Concerto Italiano’s recording of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos.

“Life imitates art far more than art imitates life.” Oscar Wilde’s mischievously challenging line appears across the opening frame of a film about Concerto Italiano’s recording of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos.

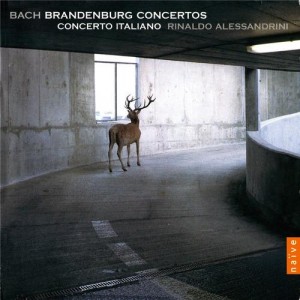

The film came unexpectedly into my hands. I hadn’t listened to the Brandenburgs in a while, and felt a need for their exuberating uplift. So I got the CDs from my public library, not knowing these performers but taking a chance on them.

I was wowed by the crisp liveliness of their performance. And delighted to discover that, along with the CDs of the six Brandenburgs, came a 2005 DVD about Concerto Italiano’s recording process, featuring interviews with their director, Rinaldo Alessandrini.

Alessandrini thoroughly enchanted me. Sporting the scruffy look, he spoke brilliantly, with a thoughtful twinkling joy, about baroque music.

The speed and invention of Italian baroque music—as with Bach’s Brandenburgs, which were inspired by the Italian baroque—force us to maintain a lightness in performing. It requires us only to bring out its elegance, its beauty, to make it speak very calmly. For the audience, it becomes a calm, cordial communication.

Baroque music as conversation: Alessandrini kept returning to this metaphor.

Bach’s music, like Monteverdi’s is a conversation: each instrument or voice can bring up a subject, listen, get a response. As performers, we have to give equilibrium to the conversation. In Italian baroque, there’s only one speaker at a time; the others are listening. In Bach’s music, everyone is making suggestions; so to avoid confusion for the listener, we have to take it apart, understand each voice, then reassemble it with the simulation of perfect clarity.

Then “simulation” became Alessandrini’s key term. “Baroque is a music of simulation. The art of simulation is a very refined art. Every day, one learns to add more details—more subtle and refined ways of playing.”

Hearing Alessandrini expand on the virtues of simulation, I had to readjust my sense of the term. I’m used to its negative connotation, its sense of feigning, faking, even dishonesty. But what Alessandrini said next helped me:

I like a book of Diderot’s, where he speaks of two different ways of approaching a text: with passion and instinct, or with technique. I find technique much more interesting—because with technique, with the art of simulation, one can handle so many details, so much refinement of the music.

So simulation is an art, synonymous with technique. That certainly raises its status.

Alessandrini continued by engaging Wilde’s twist:

I find that baroque music allows me to express what I feel. Or, in Oscar Wilde’s paradox, ‘Life imitates art far more than art imitates life’. So when we listen to music, or look at a painting, or architecture, we’re trying to simulate something that doesn’t exist, but that has been invented. But how many times have we dreamt of living in an opera? Or wished our life could end like a Hollywood film? My own life is dedicated to the imitation of baroque art. To live baroque art, to live the possibilities that baroque art offers us, to me is almost perfection.

Well, I could hardly hear Alessandrini’s statement without wondering: what era of art do I want my own life to imitate?

Definitely not the Romantic.

It happens that I also recently watched the 2003 BBC film Eroica, about Beethoven’s creation—in his Third Symphony—of the first Romantic music. The film marvelously captures the sense of witnessing something utterly and subversively new being created before our eyes (and in our ears). The young Beethoven, with wild hair and impulsive body language, is the embodiment of the passions expressed in his new symphony.

The film has the aged Haydn enter just at the symphony’s Finale. Worn out and tired of life, he is a metaphor for the exhaustion of classical music—as its death is being pronounced by Beethoven’s Third Symphony. “The only thing I can remember,” Haydn says on entering, “is striving for a balance between the emotions and the intellect. The key, as ever, is restraint.” To which Beethoven brusquely replies, “I’m not very good at restraint.”

When the finale is over, the film gives Haydn the words for what’s happening in the radical change from his own music to Beethoven’s.

He’s done something no other composer has attempted: he has placed himself at the center of his work. He gives us a glimpse into his soul—I expect that’s why it’s so noisy. But it is quite, quite new. The artist as hero. Everything is different from today.

Yes, the “noisy” soul exposed! This is Romanticism. I’m grateful for it…for all the Romantic arts. They freed us to recognize and express our passions. But is this the art I want my life to imitate? No! I don’t want to live at passion’s mercy, without restraint.

How about twentieth—and now twenty-first—century music? I love its edginess, its unpredictability, its breaking down of harmonic structures. I’m stimulated by its play with traditional forms, teasingly picking them up only to leave them hanging as the music goes somewhere I can’t quite follow.

But is this the music I want my life to imitate? No! I don’t want to live on edge, at the mercy of unpredictability, of harmonies breaking apart. When I come home from enjoying a concert of contemporary music, I want my home to be where I left it—not spirited away like Dorothy’s in The Wizard of Oz.

So…I think I’m with Alessandrini. The baroque is the art I want my life to imitate. I want to live the baroque’s balanced conversational style: its expressing, then listening, then expressing. I want to live its clarity, its lightness, its calm even in confusion or darkness.

Notice I’m saying I want to. I’m nowhere near achieving “baroqueness” in my life. If I keep listening to Monteverdi and Vivaldi and Bach’s Brandenburgs, will I get there?

Note: A selection of Bach’s Brandenberg Concertos conducted by Allessandrini will be released on August 27 by La Collection Naïve.

Peggy Rosenthal is director of Poetry Retreats and writes widely on poetry as a spiritual resource. Her books include Praying through Poetry: Hope for Violent Times (Franciscan Media), and The Poets’ Jesus (Oxford). See Amazon for full list. She also teaches an online course, “Poetry as a Spiritual Practice,” through Image’s Glen Online program.