Back in olden times, when there were only 3 networks and a slurry independent UHF of stations broadcasting B movies and 4H quiz shows on Saturday mornings, the big thing to look forward to was, The Wonderful World of Disney on Sunday nights.

It tended to feature plucky kids on the prairie or loyal pets coming to the rescue. I also remember some man against nature stuff, as well as state of the art nature documentaries.

And because Walt Disney’s shadow still covered the earth, it was wholesome, middle-America, clean-livin’ prevails entertainment. I liked it; I miss it.

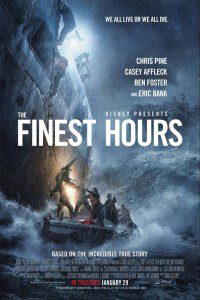

Disney’s new feature film, The Finest Hours is The Wonderful World of Disney on the big screen.

Imagine the old show brought up to contemporary standards and you have it. I saw it in 3-D. Do it if you can, it’s fabulous.

Best of all, it’s based on true events, including what many knowledgable people believe to be the greatest small craft rescue at sea in the history of the United States Coast Guard, the rescue of 32 men from the SS Pendleton, a tanker that had been torn in two in hurricane force wind off the coast of Chatham on Cape Cod, on February 18, 1952. Boatswain Mate First Class, Bernie Webber (played well by Chris Pine) led three men in a 36 foot motorized lifeboat to the aid of the Pendleton.

Now if you’re the sort of person who believes that everyone who lived before you were born was stupid, or if you’re a smirking pajama boy who looks at the moral strictures of earlier times with jaundiced eye, you would probably hate The Finest Hours.

But if you believe that heroism can be displayed in the line of duty, by people you would never suspect were capable of it, well, you’ll love, The Finest Hours.

Here’s a little taste of it…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R-XsppzuH-kMy take

(If you can’t enjoy a film if you know what’s going to happen, look away. Come back later to see what you think about my observations.)

I lived on Cape Cod and was a pastor there for nearly a decade. Some of the people in my congregation were from Chatham. I was even there early enough to get to know people who remember the old days, before the Cape became a tony retirement haunt for Kennedy wannabes.

(I actually had a man in my church who worked at the Kennedy compound in Hyannis and had known Jack Kennedy. Even though he was a Republican he liked JFK. He shared stories, if you know what I mean.)

The old Cape was blue collar, made up mostly of fishermen and their families. And some of the families could trace their ancestry back to the Revolution. I was pleased to hear the name of an old Cape family–there’s a Nickerson in the film, that’s a big clan on the Cape, I had a couple of them in my church. The Cape was a colorful place and still is. It has an interesting ethnic mix because of its whaling history; there is a strong Portuguese community, made of of folk originally from Portugal and Cape Verde. (I had some of those folk in my church too.) And there are several Portuguese and Cape Verdean seamen on the SS Pendleton, so they’re represented, which was also good to see.

So in terms of feel, as far as I can tell, the setting is absolutely right. The houses, the landscape, the accents (Chris Pine does a nice job with his), and the old weathered and crusty fishermen, it takes you there, the lower Cape of the early 1950s. I wished I could go back and move in.

I don’t know much more about the technical side of film making than the typical movie goer, probably less. So I won’t waste your time talking about things I don’t know about. I do have a background in ethics though, and I think I can be helpful looking at the film with that in mind. Here are three moral themes I in the film that I think are worth pondering.

The nature of heroism

One of the things you discover when you talk to people who have done brave things is they don’t understand what all the fuss is about. They were just doing their jobs, or doing what other decent human beings would have done in their places. That certainly is the case for Bernie Webber. All through the film he stresses the nature of his job and his commitment to following the rules.

There’s something both naive and comforting about that. Naive in a good sense, heroes apparently hold a higher opinion of the rest of us, and a lower opinion of themselves, than they should.

This doesn’t mean heroic people don’t get afraid, they experience fear too, just like the rest of us. But the secret to overcoming fear and doing heroic things isn’t will-power necessarily. It is focusing on the task at hand.

This comes through in a couple of ways in The Finest Hours. First, Bernie takes the lifeboat and his tiny crew over Chatham bar in a hurricane. (A bar is a submerged hill of sand that parallels the coast. When waves come crashing in in a hurricane the bar pushes them up to monstrous size.) All the on-lookers agree, it is a suicide mission. Two of his crew don’t really understand what they’ve gotten themselves into, and the third has accepted his fate with stoic resignation.

The film contains the subplot of the struggle to survive on the Pendleton. There, the ship’s engineer, Ray Sybert (played by Casey Affleck–born in Falmouth, a town on the upper Cape, by the way) who must not only use his engineering smarts to jerry-rig the Pendleton to keep her afloat long enough for the crew to be rescued, he has to convince the crew to follow his lead. (When I told a retired merchant-marine who happens to be deacon in my current church about Sybert, his eyes went wide. My deacon had been on tankers in the north Atlantic in bad weather. Harrowing stuff even on a sea worthy craft.)

Both Webber and Sybert are decisive and brave, but only because they do what must be done and keep focused on the task at hand. It’s worth noting that both men had been considered outsiders and failures by the men they came to lead. I think that’s a lesson to remember in itself. You really don’t know what people are made of until they are in the crucible.

Choices

It is a mistake to consider the choice to be brave as a choice between doing the right thing and cowardice. Often it is a choice between a good thing—living for instance, or getting back home to your wife and children (Bernie’s fiancé doesn’t want him to go)–and helping others, sometimes people you don’t even know.

That’s the crucible for Bernie. Sure, the elements had swollen to monstrous size, and pressing on took courage. But the choice to leave good things behind to press out into a doubtful venture, that was the real test. It’s a test many of us face in far less dramatic ways every day, “Should I report my boss, I think he’s embezzling, I might be wrong though, and if I lose my job, how will I pay the mortgage?” That’s the sort of thing we’re far more likely to deal with than trying to get over Chatham bar in a hurricane. But in a way, the choice is the same.

The choices Engineer Sybert makes to keep the Pendleton afloat are all calculated guesses, not sure things. But the lives of 33 men depend on being right.

Luck

My wife, who saw the film with me, was a little put off by the emphasis on luck, but I wasn’t. That may sound odd coming from a man who spells Providence with a capital. (And I’m not referring to the capital of Rhode Island.) But I think it is entirely appropriate, for a couple of reasons.

Sybert was from my wife’s school of thought. He doesn’t believe in luck and when luck is appealed to he makes his distaste known, “There’s no such thing as luck,” he says more than once.

But Sybert isn’t appealing to Providence. He’s an engineer, and to an engineer appeals to luck only sound like bad planning or laziness. And to a degree he’s right. It is only when he’s aboard the life boat that he reconsiders. When he asks Bernie how he was able to find the Pendleton without a compass (it broke going over the bar), Bernie says he was lucky. Sybert finally smiles and agrees, yes, it was luck.

Coming from anyone else it might sound like winning the Powerball. But for these men, who had done everything in their power to do what had to be done, this isn’t fatalism or superstition. This is humility. In the end they don’t see themselves as conquerors, exercising promethean powers in acts of overcoming. No, things could have worked out differently. They could have done all the things that they did and still died.

By the way, knowing this is what makes them brave. If you cannot fail, you may be powerful or super-competent, but you’re not brave. A high chance of failure is what what makes an action brave, not success.

How do I reconcile luck with Providence? I don’t need to. Viewed from below, Providence can only look like luck.

To conclude

The Finest Hours is a fine film. Something you can take the family to see. (Small children will probably find the harrowing elements too much to handle. They may not want to go to the beach.)

But it isn’t entertainment, really. I don’t know how you could call it that. It is more like moral formation.