I wrote my dissertation on Herbert. At the time, most scholarship about his poetry tried to relate him to medieval Catholic models, but I saw him, for all of his liturgical and sacramental imagery, as a poet of the Reformation. Researching that topic led me to read Luther for the first time, exposing me to the great theme in both Luther and Herbert of justification by grace through faith in the atoning work of Christ. I was greatly intrigued by both writers’ evangelical sacramentalism.

So I’m indebted to Herbert for my Ph.D. That dissertation was published and became my first book, Reformation Spirituality: The Religion of George Herbert. That boosted my career as a literary scholar, with my views on Herbert’s Protestantism now being generally accepted in the field. So thanks, George, for that. Publishing that book led me to more writing about Christianity and literature, which led me to writing about Christianity and the arts, which led me to writing about Christianity and culture. . . .So George Herbert is also responsible for my becoming a Christian author myself.

Above all, I’m indebted to George Herbert for getting me, as well as my wife (who typed my dissertation, this being before word processing computers were invented) started on the road to Lutheranism. When I got my first academic job after grad school, we visited a small town LCMS congregation, where what was taught was pretty much what we had been studying in Herbert! We took the adult instruction class and became Lutherans.

Every Maundy Thursday, I return to my favorite Herbert poem, “The Agony.” Before you read it, let me set it up for you. It begins by reflecting on how scientists (called “natural philosophers” in his day) measure things: the heights of mountains, the depths of the oceans, and–anticipating quantitative social science by 400 years–the dynamics of societies and politics.

But there are two “vast, spacious things” that would be even more worth measuring, yet few people even try to comprehend their heights and depths: sin and love.

If you want to know the magnitude of sin, says the poet, go to the Mount of Olives, to the Garden of Gethsemane, where you will see a Man sweating blood. Herbert uses the imagery of a man under pressure. Again, Herbert is anticipating by 400 years what has become a common way of describing intense psychological stress.

The word “Gethsemane” means “olive press,” and Herbert uses that imagery to describe the sin of the world that is pressing down on Jesus, like an olive being pressed for its oil, or, picking up on the next stanza and the imagery of blood, like a grape in a winepress. “Sin is that press and vice” [get it? another implement of pressure and also a synonym for sin, Herbert loving puns the way he does], “which forceth pain/ To hunt his cruel food through every vein.”

If you want to know the magnitude of love, also go to the Mount of Olives, and beyond that to the Mount of Calvary where it leads. Herbert describes how the soldier pierced Christ on the cross with a spear (a “pike”) in terms of someone tapping a cask of wine (see the definition of “abroach“). Whereupon the poem ends with a startling and unforgettable sacramental image.

OK, I think you’re ready to read the poem now. . . . (I have modernized some of the spellings.)

Philosophers have measured mountains,

Fathomed the depths of seas, of states, and kings,

Walked with a staff to heaven, and traced fountains:

But there are two vast, spacious things,

The which to measure it doth more behove:

Yet few there are that sound them: Sin and Love.

Who would know Sin, let him repair

Unto Mount Olivet; there shall he see

A man so wrung with pains, that all his hair,

His skin, his garments bloody be.

Sin is that press and vice, which forceth pain

To hunt his cruel food through every vein.

Who knows not Love, let him assay

And taste that juice, which on the cross a pike

Did set again abroach; then let him say

If ever he did taste the like.

Love is that liquor sweet and most divine,

Which my God feels as blood; but I, as wine.

Love is the blood that Christ pours out for us on the cross! Christ bleeds in agony, and yet when we receive His blood, His love, to us it is “sweet and most divine.” Indeed, this collision of sin and love–our sin and Christ’s love–manifests itself tangibly every time we receive Holy Communion. What “my God feels as blood”–the spiritual agony of Gethsemane, the physical agony of the cross–we experience, we “taste,” as sweet, sweet wine.

Our sin: Christ’s love. Christ’s suffering: our salvation. This is the atonement. This is the Gospel.

When you take Communion–on Easter as the climax of Lent and every other time–receiving Christ’s body that was broken for you on the cross and His blood poured out for the remission of all of your sins, think of these lines:

Love is that liquor sweet and most divine,

Which my God feels as blood; but I, as wine.

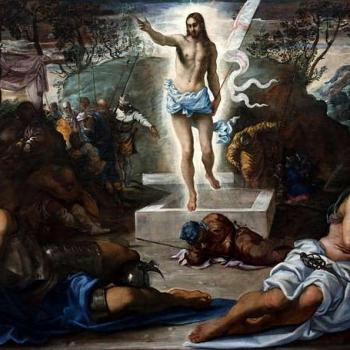

Illustration: The Agony in the Garden by El Greco via Picryl, Public Domain