A favorite Lenten hymn, especially suited to Good Friday, is “My Song Is Love Unknown” (LSB 430). Here is a congregation, St. Paul Lutheran Church in Austin, singing it, with the video helpfully showing the lyrics. (There is a rather long prelude, but the hymn gets started at 1:07.)

The hymn is based on two poems by George Herbert, whom I blogged about yesterday.

CPH published the 2-volume Lutheran Service Book: Companion to the Hymns, which gives background information and commentaries on each hymn in the Lutheran Service Book. I wrote the entries for nine hymns, including this one.

In my commentary, I explain how the hymn writer Samuel Crossman drew on Herbert. I then discuss the hymn itself.

Since I brought up Herbert, I thought I’d share part of that entry. Both Herbert’s poems and Crossman’s hymn make for very affecting devotions for Good Friday:

Text Background

The seventeenth century in England was a golden age of Christian poetry, from the intensely personal metaphysical verse of John Donne to the epic Biblical retellings of John Milton. These poems were not originally intended as hymns, though some were set to music in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. “My song is love unknown,” with its haunting melody by the twentieth-century composer John Ireland, has as its text a poem by the Anglican clergyman Samuel Crossman (1624–83), who in turn drew on the work of arguably the greatest devotional poet in English literature, George Herbert (1593–1632).

The poem beginning “My Song is love unknown” was first published in 1664 in a collection of Crossman’s poems titled The Young Man’s Meditation. An epigraph on the title page is a quotation credited to “Mr. Herbert’s Temple,” which is from the first stanza of Herbert’s opening poem, “The Church-porch,” in his collection The Temple (lines 5–6):

A Verse may find him whom a Sermon flies,

And turn delight into a Sacrifice.Crossman’s volume contains only nine poems—Herbert’s had 167—but, as with The Temple, he includes a sequence of poems on the death of Christ, the Christian life, the Last Judgment, the resurrection of the body, and heaven. Crossman’s verse lacks the poetic complexity of Herbert’s, but they share a highly personal tone, a close relationship with Christ whom both poets dare to call “friend,” and a language of paradox, irony, and wonder.

In “My Song is love unknown,” by far the best poem in the collection, Crossman begins with an allusion to Herbert’s poem “Love Unknown,” a symbolic exploration of the mysteries of God’s love in the midst of human suffering. The poem as a whole, however, is related to Herbert’s meditation on the passion of Christ, “The Sacrifice.” This 252-line poem is written from the point of view of Christ Himself. It explores the paradoxes of the Cross, specifically, the conflict between human sin and Christ’s love. “They condemn me all with that same breath, / Which I do give them daily” (lines 69–70); “They choose a murderer” and condemn “the Prince of peace” (lines 113, 118); “Behold, they spit on me in scornful wise, / Who by my spittle gave the blind man eyes” (lines 133–34).

Each four-line stanza in Herbert’s poem ends with a one-line refrain: “Was ever grief like mine?” At the climax of the poem, when Christ is forsaken by His Father, the poetry breaks off completely and the refrain changes:

But O my God, my God! Why leav’st thou me,

The son, in whom thou dost delight to be?

My God, my God———

Never was grief like mine. (lines 213–16)

Crossman both repeats and reflects upon that climactic line, which appears again as the very last line of “The Sacrifice,” in the final stanza of his own poem:

Never was love, dear King,

Never was grief like thine.

To sing this hymn during Lent is to recover an evangelical version of an ancient liturgical tradition. Herbert’s poem goes back to the “Reproaches” in the Catholic liturgy for Good Friday, in which Jesus addresses His crucifiers. That liturgy, which depicts Jesus contrasting his kindness to the Jews with their ill treatment of Him, is designed to make worshipers feel guilty at their complicity in Christ’s death. Herbert’s version, though, changes the Reproaches to emphasize the Gospel. Crossman, changing Christ’s direct address to a third person meditation, uses the tradition to explore the “love unknown” manifested in Christ on the Cross.

Text Discussion

The “love unknown” that constitutes this “song” is the love of Christ for sinners; specifically, “my Savior’s love to me.” That love is unknown not only because some people do not realize what Christ has done for them, but also and especially because His love is unfathomable, defying human reason, abounding in contradictions. He shows “love to the loveless” to make them “lovely.” He loves the very people who crucified Him. Not only that, as Crossman personalizes the Biblical narrative, He loves and died for me.

Not only Christ’s love is unfathomable; human sin is unfathomable. Even though Christ came down from heaven to bestow salvation, “men made strange and none the longed-for Christ would know.” They longed for Him, and yet they rejected Him. Sometimes, as at Palm Sunday, they would sing His praises with hosannas. But soon thereafter these same people would cry out “Crucify Him!”

What did Jesus do to deserve this treatment? He healed their diseases. Throughout, Crossman is contrasting the love of Jesus with the hatred that human beings give Him in return. They respond to Jesus’ goodness to them with “rage and spite,” being “displeased” with Jesus to the point of saving the life of a murderer—Barabbas—and slaying “the Prince of Life.” And yet, the “love unknown” of Christ is at work nonetheless.

Yet cheerful He

To suff’ring goes

That He His foes

From thence might free.

Jesus goes to suffering precisely so that He can free His foes from their inexplicable sinfulness.

Throughout, Crossman is writing not just about Christ’s crucifiers; he is writing about himself, so that those who sing this hymn also put themselves in the position of the “loveless” sinner whom Christ loves. After summarizing Christ’s incarnation to redeem the world’s sinners in the first stanza, Crossman asks,

Oh, who am I

That for my sake

My Lord should take

Frail flesh and die?

Christ became incarnate and died not only for the human race in the abstract, but “for my sake.” Crossman dramatically collapses the historical with the personal in stanza 6, when he refers to Christ’s burial in a tomb given by a “stranger”; Joseph of Arimathea’s tomb becomes “my tomb,” the poet’s and the singer’s:

Heav’n was His home

But mine the tomb

Wherein He lay.

Christ died my death and was buried in my tomb as my substitute. Coming to know the magnitude of Christ’s love for them, the speaker of the poem and the singer of the hymn respond with love for Christ:

This is my friend,

In whose sweet praise

I all my days

Could gladly spend!

You will notice some of the same themes that we saw yesterday in “The Agony,” such as unfathomable depths of human sin and Christ’s love.

I also urge you to buy, get your church to buy, or put on your wish list the book this came from, the Lutheran Service Book: Companion to the Hymns. Yes, it’s expensive at $199.99 (less than two hundred dollars!), but it’s two mammoth volumes including this kind of treatment for 656 hymns, plus 680 biographies of the composers and lyricists, plus 17 essays and much more. In unpacking every hymn, it makes the hymnal come alive, both in our singing and in our devotions.

May all of you know the goodness of Good Friday and the joy of Easter!

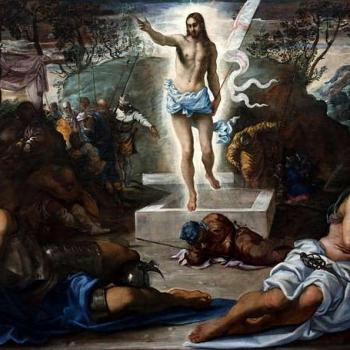

Illustration: Crucifixion by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1538) via photograph by Sailko – Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65217069