Spencer Klavan is the author of Light of the Mind, Light of the World: Illuminating Science Through Faith, which shows how quantum physics has shaken the materialist worldview and how contemporary science is making theism credible again. It’s one of the three recent books that we discussed that are being hailed as “game changers” in contemporary apologetics.

He has written an essay on his New Jerusalem Substack entitled American Revival: A nation with the soul of many churches. He believes that a revival of Christianity is brewing in the United States, seeing signs such as the new openness to religion among Generation Z men and Silicon Valley technologists, plus the surge in Bible sales and some prominent converts.

He observes that religion is deeply embedded in American culture. He describes four strains of American Christianity that date from colonial times and that have been historically formative. And he expects a Christian revival to emerge along those same four lines.

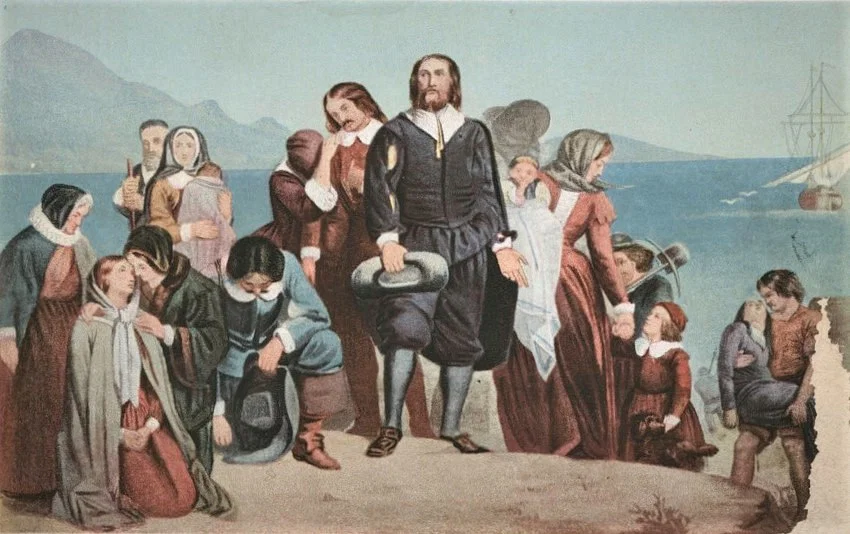

(1) The Puritans of New England sought a personal piety, moral lifestyles, and social reform. Klavan sees the heirs of the Puritans today to be the Evangelicals, who continue to win converts and exert a political influence.

(2) The Anglicans of the South valued the rites, the ceremonies, and the traditions of the English church. The equivalent today, Klavan says, are the Catholics, who are attracting people today with their “high liturgy and deep traditions.”

(3) The Quakers of Pennsylvania and the Delaware Valley offered a less doctrinal, highly personal, more mystical Christianity. Klavan sees this spiritual mindset manifesting itself in what he calls the “Nearly-Nones,” the spiritual-but-not-religious folks who are still not going to churches but who have started to read the Bible, pray, and talk about Jesus.

(4) The Frontiersmen of the West, whom Klavan describes as “the hardbitten warriors who tamed the backcountry, defiantly independent in their theology as they were in their rough ways of life.” These pioneers typically held intense but highly individualistic religious beliefs, starting new theologies (e.g., the Pentecostals), new church bodies (e.g., the Restoration movement), and even new religions (e.g., the Mormons).

Their modern equivalent? Here is what Klavan says:

Certainly one group of people is growing more comfortable with the Christian label than anyone might have expected a decade ago. There’s an intellectual vanguard—philosophers, critics, artists, tech entrepreneurs—making the high-minded case for belief. The most recent was Larry Sanger, co-founder of Wikipedia, who can’t yet sign up for any particular denomination but who recently described at length his decision that “I should admit to myself that I now believe in God, and pray to God properly.” Before Sanger came Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Matthew Crawford, Peter Thiel. There are enough of them now to be called a movement.

These are surely our frontiersmen. Like the old frontiersmen, they favor adventurous and dramatic theology for their adventurous and dramatic circumstances. They are prone to grand theories about the end times and the clash of civilizations, all of which figures. Those in tech, especially, work at the edge of humanity’s limits in a perilous new age of exploration. They are among those pressing forward into outer space, into the workings of the body and brain, into machine capabilities. Out in that dark wilderness there are rival and even savage faiths, preached by babel-builders who want to kneel before AI superintelligence or hail a rising one-world government. It’s dangerous to ride the high country without a map, and Christianity is a time-tested one, well-known for keeping its followers from dropping into snake pits.

These four are not completely different, Klavan says. They all hold to some common articles “articles of faith—the triune God, the resurrection, the forgiveness of sins—without which Christianity is not Christian.” (It’s interesting that mainline liberal Protestantism, which tries to have Christianity without such articles, doesn’t even show up on Klavan’s religious radar.)

He concludes with C. S. Lewis’s metaphor of Christianity as a building, with “mere Christianity,” what all Christians have in common, being the hallway, off of which are different rooms, the various Christian traditions. Lewis stresses that Christians, who might start in the hallway, must enter one of the rooms: “It is in the rooms, not in the hall, that there are fires and chairs and meals. The hall is a place to wait in, not a place to live in.”

Klavan adds to the metaphor: “The building might need all the rooms—all the passion of the evangelicals, all the ancient solemnity of the Catholics, all the longing of the nearly-nones and wild-eyed mysticism of the pioneers—to stand.”

Sounds like Lutheranism to me! Well, up to a point.

Klavan’s four colonial strands derive from England, of course, as does American culture. Many other peoples with many other religions also became part of America. Such as us Lutherans from northern and eastern Europe. We don’t fit neatly into any of those four categories.

If you bring some of them together, though, we might come closer. Confessional Lutheranism has both the evangelicals’ emphasis on the Gospel and the Bible, plus the “ancient solemnity” associated with the Catholic liturgy and Catholic sacramentalism. Today’s “new theists” attracted to both evangelicalism and Catholicism and trying to decide between them would do well to consider Lutheranism.

Many Christians so torn go the Anglican route, but that’s a via media between the two traditions. Lutherans are very evangelical and very sacramental.

Lutheranism arguably has a higher view of the Gospel (not just as a one-time “decision” but as the continual source of the Christian life) and the Bible (not just as a fact book but as a means of grace). And a higher view of the Sacraments than Catholics (with the “sacramental union” being far more incarnational than transubstantiation, which dismisses the physical elements as mere illusions).

I find Lutheran Christianity very “spiritual,” but not in the open-ended non-doctrinal inwardness of the Quakers and the “nearly-nones.” Lutheran spirituality rests on the objective truths revealed in the Word of God.

I find Lutheran Christianity very emotionally satisfying to me as an individual, but not in the individualistic, go-it-alone, look-for-something-new spirit of the “frontiersmen.” Lutheran Christianity needs a congregation and a pastor, sees itself as continuous with historic Christianity, and has a high view of church.

For me, Lutheranism was what tied the other strands of Christianity–not just these four, but many others–together.

(For more about Lutheranism, see my book Spirituality of the Cross: The Way of the First Evangelicals and, especially for Lutherans in need of recovering their heritage, my newest book Embracing Your Lutheran Identity.)

Illustration: “The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in America, A. D. 1620“, (1848 CE) by Charles Lucy (1814–1873 CE). White House copy of the painting. (From The White House Historical Association), via World History Encyclopedia, CC BY 4.0.