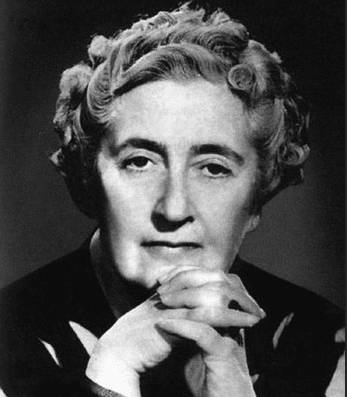

There is a connection between the great mystery writer Agatha Christie, controversies among Catholics about the Latin mass, and the two senses of mystery.

I will explain this by roughly following the structure of a mystery novel. . .

The Setup

Traditional Catholicism is making a big come back, especially among young people, and it’s centered in the Tridentine Latin mass. So Pope Francis has been trying to squelch that by putting out a decree forbidding the use of that liturgy without a specific dispensation from the Vatican.

Some conservative bishops and priests, though, are disobeying their liberal pope by conducting the Latin mass anyway. Now a supposedly well-sourced rumor is circulating that the pope will ban the Latin mass completely.

We Reformation Christians don’t really have a dog in this fight. Luther supported worship in the vernacular, though Lutherans continued to celebrate the Divine Service in Latin sometimes. After all, Latin was the common language, the lingua franca, of Europe through much of the 18th century, so international meetings and, especially, academic gatherings were conducted in Latin. In fact, Latin was the vernacular in schools and universities. Luther simply wanted worshippers to understand what they were hearing and saying, and sometimes that required worship in Latin.

As for the mass, Lutherans are confessionally obliged to claim that for themselves. “Falsely are our churches accused of abolishing the Mass,” says the Augsburg Confession, Article XXIV, “for the Mass is retained among us, and celebrated with the highest reverence,” adding “Nearly all the usual ceremonies are also preserved.” To be sure, the Lutherans reformed the Roman mass by taking out prayers to the saints, the emphasis on merit, and other theological errors. But Lutheran worship remains liturgical.

Also, Pope Francis hasn’t restricted the use of the Latin language for the mass, as such. It’s still possible to say the modern order of the liturgy in Latin, as in any other language. What he is opposing is the Tridentine rite, which came out of the Council of Trent, a product not of the Middle Ages–the one that Luther knew–but of the Counter-Reformation. So it has even more things in it that Lutherans and other Protestants object to.

But Catholics, like Lutherans and other Protestants, have had their “worship wars,” and contemporary worship won out. To be sure, Catholic contemporary worship is still more liturgical than the typical evangelical praise service, but, since it was a product of Vatican II, its music and wording shows the influence of the Sixties, making it sound even more dated and, for conservative Catholics, sometimes cringeworthy.

So we Lutherans can sympathize with Catholics who love the pre-Vatican II Latin mass, with its rich language and its ethereal, beautiful music. And it isn’t just schadenfreude to see conservative Catholics, usually the most ardent defenders of the papacy, opposing their pope for undermining Christian orthodoxy. Now they know how Luther felt.

The Discovery

In 1971, Pope Paul VI was also considering banning the Latin mass. A number of British luminaries wrote the Pope a letter urging him to allow the Latin mass. Some of the signers were well-known Catholics, like Graham Greene and Malcolm Muggeridge. Others, though, were non-Catholics–such as Sir Kenneth Clark and poet laureate Cecil Day-Lewis–with even some non-Christians–such as the communist Philip Toynbee, the atheist novelist Iris Murdoch, and the Jewish violinist Yehudi Menuhin– joining the cause.

As K. V. Turley tells it in an article on the subject in the National Catholic Register,

In total there were 57 names attached to the letter that stated that its signatories were not preoccupied with “the religious or spiritual experience of millions of individuals”; instead, they wishes to highlight how “the rite in question, in its magnificent Latin text,” had “also inspired a host of priceless achievements in the arts — not only mystical works, but works by poets, philosophers, musicians, architects, painters and sculptors in all countries and epochs. Thus, it belongs to universal culture as well as to churchmen and formal Christians.” Their concerns regarding this rite were with what they believed to be “a plan to obliterate that Mass by the end of the current year.” Therefore, the signatories of the appeal wished “to call to the attention of the Holy See the appalling responsibility it would incur in the history of the human spirit were it to refuse to allow the Traditional Mass to survive, even though this survival took place side by side with other liturgical forms.”

The pope read the letter and looked over the names, most of which he probably didn’t recognize. But then he saw one that he did, the Queen of Crime. “He exclaimed: ‘Ah, Agatha Christie!’ and promptly agreed to the letter’s plea.”

Pope Paul VI signed what became known as the “Agatha Christie Indult” (meaning permission for an exception to church law), which preserved the Latin Mass.

The Funnel

So why did Agatha Christie want the pope to preserve the Latin mass?

We know that she was a high-church Anglican. Her husband was a Catholic, who continued to attend Mass even though he couldn’t receive communion because he married Agatha, a divorcee. She probably attended with him sometimes, though she also regularly attended her own congregation.

She didn’t write about religion per se, but her portrayals of clergy and the church are always quite positive. Hercule Poirot is a Catholic, and Miss Marple is an Anglican, with vicarages and vicars playing prominent roles in many of her stories.

Turley offers some speculations about her possible interest in Catholicism, such as her keeping her late mother’s copy of The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis by her bedside for the rest of her life. But that devotional classic would not be unusual for an Anglican or any other Protestant to read. It is evidence, though, that Christie was a believing Christian.

It so happens that I have been on an Agatha Christie binge lately. We’ve been streaming Poirot and Miss Marple, and they are so good, far beyond the typical detective fare, that I decided to read the books, which are often quite different from the TV dramatizations, as good as those are.

I had associated Christie with “cozy mysteries,” that subgenre in which little old ladies sit around drinking tea as they solve sanitized crimes. But her stories can be dark and disturbing enough for anyone who believes as she did in original sin, and this is especially true of those starring Miss Marple, a little old lady indeed, whose effectiveness in detecting murderers comes from knowing, as she says, how wicked people generally are.

And Christie is a brilliant writer! Yes, her books are entertainment, not psychological novels, but her characters come alive, her descriptions pop off the page, and her dialogue is full of wit and verve. But her genius is evident in her plots. Their twists and turns are dazzling.

Another aspect of her genius is that, as an early pioneer of the genre, she is creating the conventions of the mystery story, which are still evident to this very day in books, TV, and movies. But she also plays with those conventions–pushing them in new directions, turning them upside down, and even violating them–so that the reader is always taken by surprise.

You can get some of them on cheap Kindle collections, but these generally leave out the most celebrated novels such as Murder on the Orient Express and Death on the Nile, (When those collections say they are the “complete” novels, they are anything but, consisting of a few novels and many short stories.)

My favorites with Poirot are The Murder on the Links and The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, both of which left my head spinning. My favorite Miss Marple is A Murder Is Announced.

But what is the connection between Agatha Christie’s mysteries and her interest in Christian liturgy, not only in getting the pope to allow the Latin mass but in her own life as a church-going high church Anglican devoted to the Book of Common Prayer?

The Reveal

My friend the Australian theologian John Kleinig provides the clue. In his book God’s Word: A Guide to Holy Scripture, he writes,

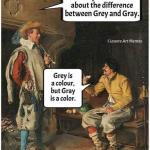

Like many modern people, we tend to confuse mysteries with secrets. And so we explain them away. But a mystery is different from a secret. Even though both have to do with something that is hidden and unknown, a mystery differs from a secret in one important respect. A secret remains a secret only as long as you don’t know it. Once it is revealed, it ceases to be a secret. But a mystery remains a mystery even when it is revealed. In fact, the more you know about it, the more mysterious it becomes. (p. 126)

Agatha Christie writes about secrets, to be sure, but somehow her books, unlike so many others in the “mystery” genre, can be read with profit and enjoyment over and over again, even after you know “who dunnit.” This is because she evokes the mysteries of human beings, of ordinary life that is Miss Marple’s stage, and what the Bible describes as “the mystery of iniquity” (2 Thessalonians 2:7; KJV).

Among the mysteries that Kleinig cites–of which “the more you know about it, the more mysterious it becomes”–are Christ, meditation on Scripture, prayer (see his book Grace Upon Grace), and worship, specifically, the Divine Service, what Lutherans call the historic liturgy.

So no wonder the Queen of Crime would not only create fictional mysteries but that she would also treasure the mysteries of the church, expressing her sense of mystery by writing both stories for the public and a letter to the pope!

Photo: Agatha Christie plaque -Torre Abbey.jpg: Violetrigaderivative work: F l a n k e r, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons