It turns out, philosophers

have written about the Holy Communion. Even

modern philosophers; that is to say, post-Enlightenment philosophers. Leithart’s article is a review of

The Eucharist in Modern Philosophy by the French Catholic theologian Xavier Tilliette (1921-2018).

Tilliette’s book focuses on Catholic thinkers and their understanding of transubstantiation, but he includes some Lutherans and LINOs (Lutherans In Name Only).

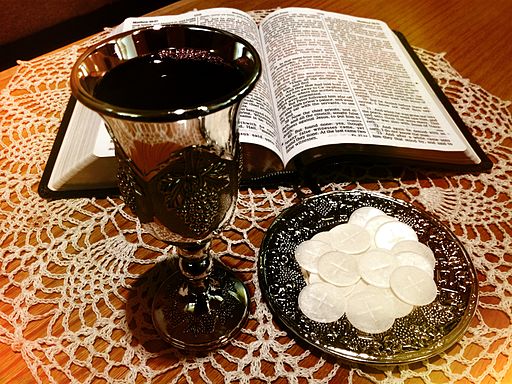

Leithart says that a full consideration of the issue should include a thorough treatment of Protestant thinkers, with their various understandings of the Sacrament. I would add that a distinctly Lutheran approach recognizes the difference between philosophy and theology, reason and revelation, insisting that the Sacrament can never be understood by human reason but must always be known by and through the Word of God, which not only describes but creates the Sacrament.

As a result, Lutherans avoid such philosophical concepts as “substance” when referring to Christ’s presence in the Lord’s Supper. Not only Catholics but the Reformed insist on “substance” language, to the point of using terms like “consubstantiation” to describe the Lutheran position, a term that Lutherans themselves reject. Instead, they use theological language such as “sacramental union” and “in, with, and under” to describe Christ’s real presence in the bread and wine.

Still, Leithart recounts some interesting and provocative thoughts from philosophers who, sometimes to my surprise, took the Sacrament seriously. They are not so much philosophical explanations as more in the nature of philosophical implications of Christ coming to us in bread and wine. Here are some samples:

Franz von Baader’s essay “On the Eucharist” begins with an account of the “hidden mystery in the nutritional process in general,” which he believed to be an undeveloped theme of traditional theology. Following Aquinas, he pointed to the miraculous reversal of spiritual nourishment: Instead of being absorbed into the eater, spiritual food absorbs the eater into itself, so the Eucharist becomes a nuptial feast of union between Christ and his bride.

For Maurice Blondel, transubstantiation is “a prelude, under the veils of mystery, of the final assimilation, of the supreme incorporation of all that exists to the Incarnate Word.”

Leibniz [a Lutheran] introduced the mysterious concept of a “substantial bond” that united soul and body, the natures of Christ, and the living Christ to bread.

On his deathbed, Schleiermacher [a LINO] proclaimed the words of institution “are the foundation of my faith,” the focal point of mystical union with Christ in the community of love. The Supper, he wrote, is the highest means for “maintaining living fellowship with Christ,” and every other means of communion is “either an approximation to it or a prolongation of it.”

It’s interesting that Schleiermacher, who stressed that religion involved not objective truths but subjective religious feelings and is considered “the father of liberal theology,” nevertheless had such a high view of the Sacrament. I suppose that it has to do with Schleiermacher’s emphasis on religious experience. That can certainly lead us astray, as it led him. But his deathbed thoughts remind us that partaking of the Lord’s Supper is an experience, the right kind, an experience of Christ and the Gospel.