First academia threw out religion. But then religion was replaced with “Western Civilization” as the source of values, inspiration, and all that is good. Now academia has thrown out “Western Civilization” on the grounds that the great books and great ideas that had become the focus of the liberal arts curriculum are too male, too white, and too European.

That is the thesis, in a nutshell, of Stanley Kurtz in his National Review article Two Secularizations and the Fate of Conservatism.

It has recently been argued that the sharp decline in the popularity of the humanities on campus is the result of a “second secularization,” a collapse of our regard for high culture that parallels and reflects the broader decline of religious faith. . . .

The “ultimate things” in dispute in the second secularization are the goodness, continuity, and even the very reality of Western Civilization, and of America’s place within it. From the left side, the second secularization began with works like Stanley Fish’s 1980, Is There a Text in This Class? There Fish challenged our faith in the very existence of objectivity, reality, and truth. In the wake of declining belief in God, faith in almost any anchor outside ourselves had dimmed.

We can think of politics today as the effect of continuing conservative pushback against both the first and second secularizations. Just as it has taken more than three decades for campus humanities departments to commit enrollment suicide by destroying faith in Western Civilization, the Great Books, objectivity, and reality itself, so it has taken several decades for the specifically political consequences of the second secularization to emerge.

What began as a fascinating cultural sideshow has become our politics. The dispute between campus multiculturalism and traditional American conceptions of citizenship launched at Stanford in 1987 is now the everyday stuff of our debates. Controversies over race, gender, and ethnicity are ubiquitous. The ideal of global citizenship contends with faith in America and the West. Even the core Western commitment to freedom of speech is challenged now by intersectional orthodoxy. All of this was in play at Stanford in the late 1980s. It has taken three decades, but today who we vote for has everything to do with how we see these disputes.

As someone who lived through a lot of this, both as a student and then as a professor, I found myself agreeing with Kurtz, while also noting some issues that he raises but does not fully treat.I was struck first of all by the thought–which Kurtz doesn’t emphasize too much–that the rise of “Western Civilization” courses and the ideology that came with them in the middle of the last century were attempts to fill the void left by the banishment of religious faith from academia. Notice the terminology: Scholars would speak of the “canon” of Great Books, a term borrowed from consideration of the books of the Bible. We were always being “inspired” by what we were reading. Literature and the arts were giving us “transcendent” experiences. Interpreting literature (my field) involved “hermeneutics.” We spoke of works that were”iconic,” texts that were “sacramental,” plots that contained “epiphanies.” All of these theological terms were applied to secular literature, philosophy, and art. To speak of the repudiation of Western Civilization as another “secularization” is to admit that it had been turned into a religion.Western civilization has generated lots of books and ideas, of course, and any attempt to sort through them to form a “canon” will require a principle for selection. Generally, the “canon” consisted of Greco-Roman classicism, especially Plato and Aristotle, with some Christian writers–Augustine, Aquinas, Dante, Pascal, Milton–as well as Christian-influenced authors who have stood the test of time, such as Shakespeare and Cervantes. Then the list settled down to give us the heritage of modern liberal democracy (Locke, the Federalist Papers, Adam Smith), modern science (Bacon, Newton, Darwin) and contemporary thought (Freud, Marx, Nietzsche). (See this account and list of the Great Books of the Western World, as compiled by Mortimer Adler and published by the Encyclopedia Brittanica.)To read and study all of this can result in a splendid education, far, far superior to the “critical theory” and relativism that has replaced it. But the religious content that was conveyed in the humanities curriculum in its heyday was humanism. Back then we heard a lot about humanism or “secular humanism,” both among its advocates and its critics. There was much talk even in college classrooms about things like “the triumph of the human spirit,” “human values,” “universal humanity,” “human greatness” and even how religious concerns of the past now have their fulfillment in a new “humanism.” Notice that we don’t hear much about humanism today, though we might hear on college campuses about “post-humanism” or “trans-humanism.” Even humanism is too transcendent, too religious for today’s secularists.I myself am a big advocate of classical education, classical liberal arts curricula (not in the sense of the “humanities” but in the older, more comprehensive view of the education needed to shape the free citizen), and Great Books programs. But what I advocate is “classical Christian education.” It is possible and valuable to study even the secular canon of the Great Books from a Christian rather than a humanist perspective. But Western Civilization, the liberal arts, and the Great Books are not enough to equip human beings to live a meaningful life. Though some, then and now, believe that they are.Properly, Christianity and Western Civilization can complement each other. Christianity, which has always existed in multiple cultures, was never just a matter of “Western Civilization,” though European culture was profoundly shaped by the Christian faith. European culture has much that is worth studying, preserving, and passing down, including what is not explicitly religious. The classical liberal arts (the mastery of language, in the trivium of grammar, logic, and rhetoric; and the mastery of mathematics, in the quadrivium of arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy) are not particularly culture-bound at all. Indeed, some practitioners of the Western Civilization curriculum were either Christians or, as in the case of Mortimer Adler, converted to Christianity.

The Reformers, who did so much to revive both classical education and theological education, show how it is possible to study both the secular and the sacred realms, without confusing the two, as each has its distinct place in God’s temporal and His eternal kingdoms.

But Kurtz is certainly correct that both faith and “civilization” as cornerstones of education have the same enemies and have been torn down for the same reason. He discusses William F. Buckley’s God and Man at Yale (1951), in which the recent graduate who would become one of the most important conservative figures of his day criticizes the anti-religion bias of Yale and higher education in general. Kurtz says that this book proved to be the catalyst for the modern conservative movement. He then quotes “the most controversial passage” in the book:

I believe that the duel between Christianity and atheism is the most important in the world. I further believe that the struggle between individualism and collectivism is the same struggle reproduced on another level.

Buckley was thinking about Communism, which is militantly atheistic and which also opposes liberal democracy, including its values of individualism, freedom, inalienable rights, etc.

Not just Marxists but the post-Marxists of our own day also oppose those values, as well as the civilization that gave rise to them and that has been built upon them. And they are the ones who have overthrown “Western civilization” courses on college campuses.

We could call that a “second secularization,” as Kurtz does. Or we could see this new emphasis on sex, gender, race, and privilege as a third religion, replacing humanism on college campuses, just as humanism replaced Christianity. Kurtz himself uses a whimsical version of yet another religious term to describe the phenomenon: “the Great Awokening.”

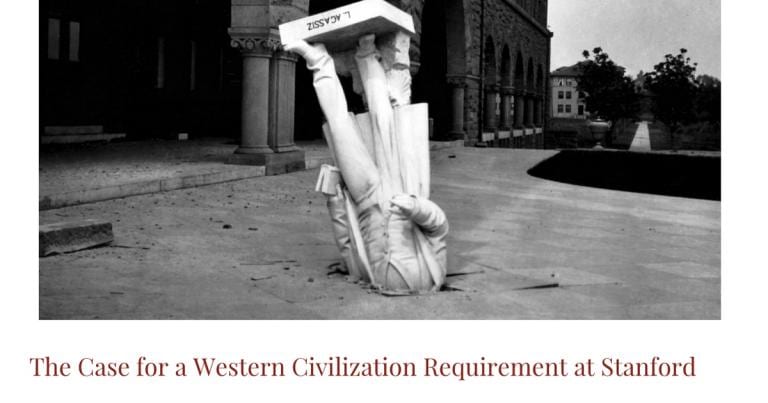

Illustration: A meme opposing a Western Civilization requirement at Stanford, incorporating the Agassiz statue, Stanford University, California. April 1906. San Francisco earthquake of 1906. Credit: ID. MENDENHALL, 715. By http://libraryphoto.cr.usgs.gov/cgi-bin/show_picture.cgi, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1710377, via Wikimedia Commons. The meme is by JASMIN KAMRUDDIN at The Tab.