Can the church use coercive power–either its own or that of the state–to achieve its spiritual goals? Most Protestants, but not all, have historically said “no.” But Roman Catholics have historically said “yes.”

In a discussion of President Trump’s messianic praise as “the second coming of God” and “the king of Israel,” Rev. Ben Johnson says that some Christians really think in those terms, looking “to a secular ruler for deliverance” and pursuing “salvation by politics.” Instead, Rev. Johnson, an editor with the free-market Acton Institute, recommends that Christians promote religious liberty and influence the culture by proclaiming and living out the Gospel, rather than through coercive power.

In the course of his article, Rev. Johnson cites something I did not realize, that the official doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church does have a role for the exercise of power that coerces people to adhere to the teachings of the church.

From Ben Johnson, The ‘King of Israel’: The Caesar strategy or cultural renewal?:

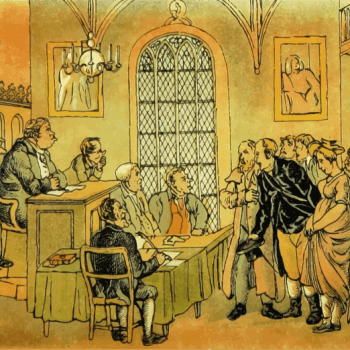

Blurring the lines of Church and State distorts both institutions. This can be seen clearly among Catholic integralists, who would deputize bishops to arrest heretics and schismatics. Thomas Pink, a philosophy professor at King’s College London, writes: “[A]ccording to traditional doctrine, the [Roman Catholic] Church has the right and authority” to enforce its jurisdiction over all baptized Christians “coercively, with temporal or earthly penalties as well as spiritual ones.” (Emphasis added.) Non-Catholic Christians may be punished by the Church for certain acts of “heresy, apostasy, and schism” in order “punitively to reform heretics, apostates, or schismatics, or at least to discourage others from sharing their errors.” Pink adds, ominously, that the Church has the “authority to use the state as her coercive agent.” (See also Pink’s response to our friend, Fr. Martin Rhonheimer.)

This violates the Gospel, which demands that human beings accept divine mercy of their own free will. A coerced faith is no faith. Heresy police would be more compatible with certain Islamic interpretations of dhimmitude than the Christian, patristic doctrine of religious liberty.

[Keep reading. . .]

The author is referring to Thomas Pink’s article in First Things, Conscience and Coercion, in which he shows that Vatican II’s affirmation of religious liberty means that the state may not coerce belief. The church, however, may, holding coercive power over the baptized, with the right to employ the state for its purposes.

From a Lutheran perspective, for the church to have authority over the state is a violation of the doctrine of the Two Kingdoms, and for the church to exercise the power of coercion in its ministry is a confusion of Law and Gospel.

This does not mean, though, that coercive power is always illegitimate and ungodly. The state is also a divinely-established institution, whose purpose is to exercise power so as to restrain evildoers and make it possible for fallen human beings to form a society. The state’s purview is the first use of the Law, curbing external sin by means of lawful magistrates, rewards, and punishments, though such external and coerced obedience can never make a person internally righteous, which is possible only through the faith that comes from the church’s proclamation of the gospel of Christ.

God works through the vocation of the governing authorities to restrain the external effects of sin, just as He works through the vocation of pastors to bring about the forgiveness of sins. Ordinary Christians, citizens of the eternal Kingdom of God, also have vocations as citizens of God’s temporal Kingdom.

Thus it is fitting for American Christians, as individuals–not the corporate church, as such–to be involved in politics and to exercise power to curb such evils as abortion and other cases of child abuse. It is not necessarily idolatry for Christians to work through the existing governmental systems to do so, even though this may involve certain compromises with the governing authorities.

But it is idolatry if we put our faith in them. As Luther explains in the Large Catechism, explaining the First Commandment, whatever you put your faith in is your god:

A god means that from which we are to expect all good and to which we are to take refuge in all distress, so that to have a God is nothing else than to trust and believe Him from the [whole] heart; as I have often said that the confidence and faith of the heart alone make both God and an idol. If your faith and trust be right, then is your god also true; and, on the other hand, if your trust be false and wrong, then you have not the true God; for these two belong together, faith and God. That now, I say, upon which you set your heart and put your trust is properly your god.

Christians must not “put their trust”–that is, their faith–“in princes” (Psalm 146:3), but this does not mean rejecting princes and the power they exercise altogether.

The Lutheran doctrine of the Two Kingdoms–typically ignored by both sides of the debates–shows how we can affirm freedom without rejecting the state altogether, how we can affirm the nation without turning it into an idol, and how we can affirm political action without politicizing the church.

Illustration by Lucas Cranach, “A King Kisses the Pope’s Feet,” in Christ and Anti-Christ via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain