If a Protestant Christians gets into a discussion with a Roman Catholic and brings up the authority of the Bible, the Catholic will often come back with a riposte like this: “What Bible? You Protestants don’t follow the Bible. You threw out seven of the books you didn’t like. At least we Catholics have the whole Bible, not the shortened version you came up with.”

Well, the truth is more complicated than that. At issue are the books of Tobit, Judith, Wisdom of Solomon, Wisdom of Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), Baruch, and 1–2 Maccabees. Also portions of Daniel and Esther. These were written in Greek, not Hebrew, and so are not considered part of the Old Testament scriptures as recognized by the Jews.

The question is whether these so-called apocryphal or “deuterocanonical” books are “canonical.” That is, whether or not they belong in the Biblical canon.

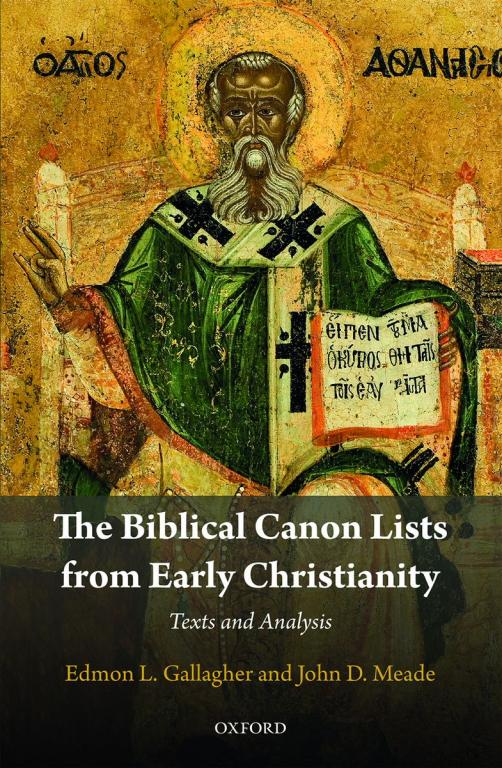

A new book on the history of this question is very illuminating. Edmon L. Gallagher and John D. Meade have published The Biblical Canon Lists from Early Christianity: Texts and Analysis with Oxford University Press.

They say that the canonicity of these books was an open question until after the Reformation, when the Council of Trent drew up a canonical list. Back in the 4th century, the apocryphal books were generally accepted in the West, but not in the East, Greek-speaking though it be. But in the West, St. Augustine included the apocryphal books in his list of the canon, scattering them through the Old Testament. But St. Jerome, the great translator of the Bible into Latin, did not accept them.

Nevertheless, St. Jerome did include them in his translation, putting them in a separate section between the Old and New Testaments. So did Luther in his translation of the Bible. So did the translators of the King James Version.

Read Gallagher and Meade’s survey of their findings in the Oxford University Press blog:

One of the side effects of the Protestant Reformation was intense scrutiny of the biblical canon and its contents. Martin Luther did not broach the issue in his 95 Theses, but not long after he drove that fateful nail into the door of the Wittenberg chapel, it became clear that the exact contents of the biblical canon would need to be addressed. Luther increasingly claimed that Christian doctrine should rest on biblical authority, a proposition made somewhat difficult if there is disagreement on which books can confer “biblical authority.” (Consider, e.g., the role of 2 Maccabees at the Leipzig Debate.) There was disagreement—and there had been disagreement for a millennium or more beforehand. Almost always, the sixteenth-century disputants pointed back to Christian authors in the fourth century or thereabouts for authoritative statements on the content of the Bible.

But fourth-century Christians themselves disagreed on precisely which books constituted God’s authentic revelation. Especially with regard to the books most in dispute in the sixteenth century—the so-called deuterocanonical books of the Old Testament—the fourth century could provide no assured guide because even those ancient luminaries, St. Jerome and St. Augustine, disagreed particularly on the status of these books.

The deuterocanonical books—as they would come to be called by Sixtus of Siena in 1566—are essentially those portions of Scripture that form part of the Roman Catholic Bible, but not the Protestant Bible. (Sixtus had a slightly wider definition of the term “deuterocanonical” [second canon].) In this sense, there are seven deuterocanonical books: Tobit, Judith, Wisdom of Solomon, Wisdom of Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), Baruch, and 1–2 Maccabees. There are also two books with deuterocanonical portions: Daniel and Esther.

In the sixteenth century, it was not clear whether these books belonged in the Bible or not; different theologians and church authorities took different positions on the matter, and there had never been a council that settled the issue for the entire church. While these books appeared in biblical manuscripts and printed Bibles, it was not uncommon in the Latin Church to question their status.

[Keep reading. . .]