I finally realized what’s wrong with movies today. What Aristotle described as the least important element of drama has become the most prominent.

So now we have a sequel trilogy, and it’s still about rebellion against the Empire! That plot line was finished! Not only that, just about every element in the original story is rehashed–another father/son darkside turn, more aliens in a bar only this time it’s a casino, another Hans Solo-like rogue, more racing alien animals, and on and on.

If there is a Star Wars universe, as we keep hearing, let different things happen! The republic that arose on the ruins of the empire can face any number of new threats. Have the remnants of the empire start a rebellion of their own! Or have an invasion from another galaxy. Or have the dark side erupt in frightening new ways. Or something!

But there is an even deeper problem with this film, one that is shared by virtually every Comic Book movie, every action thriller, every science fiction flick, many animated features, many comedies, and quite a few ordinary dramas.

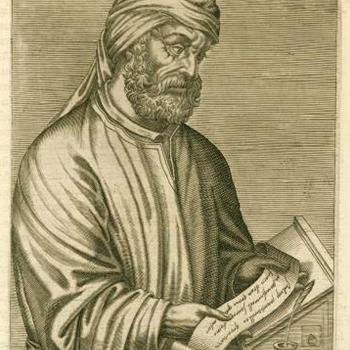

We’ll let Aristotle explain, since he anticipated the problem in the very first and still greatest treatise on drama, back in 335 B.C. In his Poetics, he lists the six elements of a play. My emphasis, from The Internet Classics Archive | Poetics by Aristotle:

The plot, then, is the first principle, and, as it were, the soul of a tragedy; Character holds the second place. A similar fact is seen in painting. The most beautiful colors, laid on confusedly, will not give as much pleasure as the chalk outline of a portrait. Thus Tragedy is the imitation of an action, and of the agents mainly with a view to the action.

Third in order is Thought- that is, the faculty of saying what is possible and pertinent in given circumstances. In the case of oratory, this is the function of the political art and of the art of rhetoric: and so indeed the older poets make their characters speak the language of civic life; the poets of our time, the language of the rhetoricians. Character is that which reveals moral purpose, showing what kind of things a man chooses or avoids. Speeches, therefore, which do not make this manifest, or in which the speaker does not choose or avoid anything whatever, are not expressive of character. Thought, on the other hand, is found where something is proved to be or not to be, or a general maxim is enunciated.

Fourth among the elements enumerated comes Diction; by which I mean, as has been already said, the expression of the meaning in words; and its essence is the same both in verse and prose.

Of the remaining elements Song holds the chief place among the embellishments.

The Spectacle has, indeed, an emotional attraction of its own, but, of all the parts, it is the least artistic, and connected least with the art of poetry. For the power of Tragedy, we may be sure, is felt even apart from representation and actors. Besides, the production of spectacular effects depends more on the art of the stage machinist than on that of the poet.

“Spectacle” for Aristotle refers to the costumes, backdrops, the machines that let down gods, bloody daggers and other props. These were not as sophisticated in 335 B.C. as they are today, but his point remains: With a good story and good characters, the stage effects don’t make that much difference either way. (Notice how a Shakespeare play tends to retain its power whether it’s in period costumes, modern dress, or a bare-bones stage.) And all of that stuff is the work of technicians, not the creative authors.

Today’s technology has given us, as we say, spectacular special effects. But now so many of today’s movies consist largely of explosions, chases, fights, an computer-animated effects. They often take up more time in a movie, or seem to, than plot or character development.

Now when we first saw the kind of special effects that today’s movie-making technology can do, we were very impressed. Actually, for many of us, the first showcase was the first Star Wars trilogy. But now we have become jaded. So much “spectacle” has become tedious. For me, at least. (How about you?)

Nothing against special effects technicians. Indeed, contrary to Aristotle, I consider themselves artists in their own right. But the best movies, like the best ancient Greek tragedies, are going to have all six of the dramatic elements working together.

Filmmakers could learn much from Aristotle. I was struck at his comment on the importance of music, which “holds the chief place among the embellishments.” Indeed, we often pay little attention to the soundtrack, which goes on subliminally, but it can add much to a film. And Aristotle gives many practical pointers on how to create a complex character, working with the audience’s sympathies, and creating “cathartic” endings.

UPDATE: We just saw a film that is an exception to my earlier complaints: The spectacle is at the service of a highly original plot, with the actors playing two different parts at the same time. The movie is Jumanji.

Illustration by J. D. Hancock, Revenge of Return of the Jedi, via Flickr, Creative Commons License