By Reed Metcalf

My experience has been that many folks struggle to understand just exactly what a “prophet” is. Understandably so: prophets are weird. Prophetic writings can be weird. But, honestly, this is a bit of the point, at least according to Walter Brueggemann.

Brueggemann is an Old Testament scholar who made a name for himself a few decades ago by writing a short but powerful book called The Prophetic Imagination. (It is by no means perfect, but a great starting point for any Old Testament delving.) At the time of his writing, the biblical prophets were caught in a tug of war between two different parts of the church. Part of the church wanted to stress the prophets’ concern simply for the future: what God would do in Jesus and at “the end of the world.” The other part really wanted to say that the prophets were only concerned with addressing the social problems of their day and age. The results were two descriptions of God’s servants: one was of an odd set of fortune-tellers, the other of glorified social-workers. Neither looked like what a prophet really was according to the biblical texts, says Brueggemann.

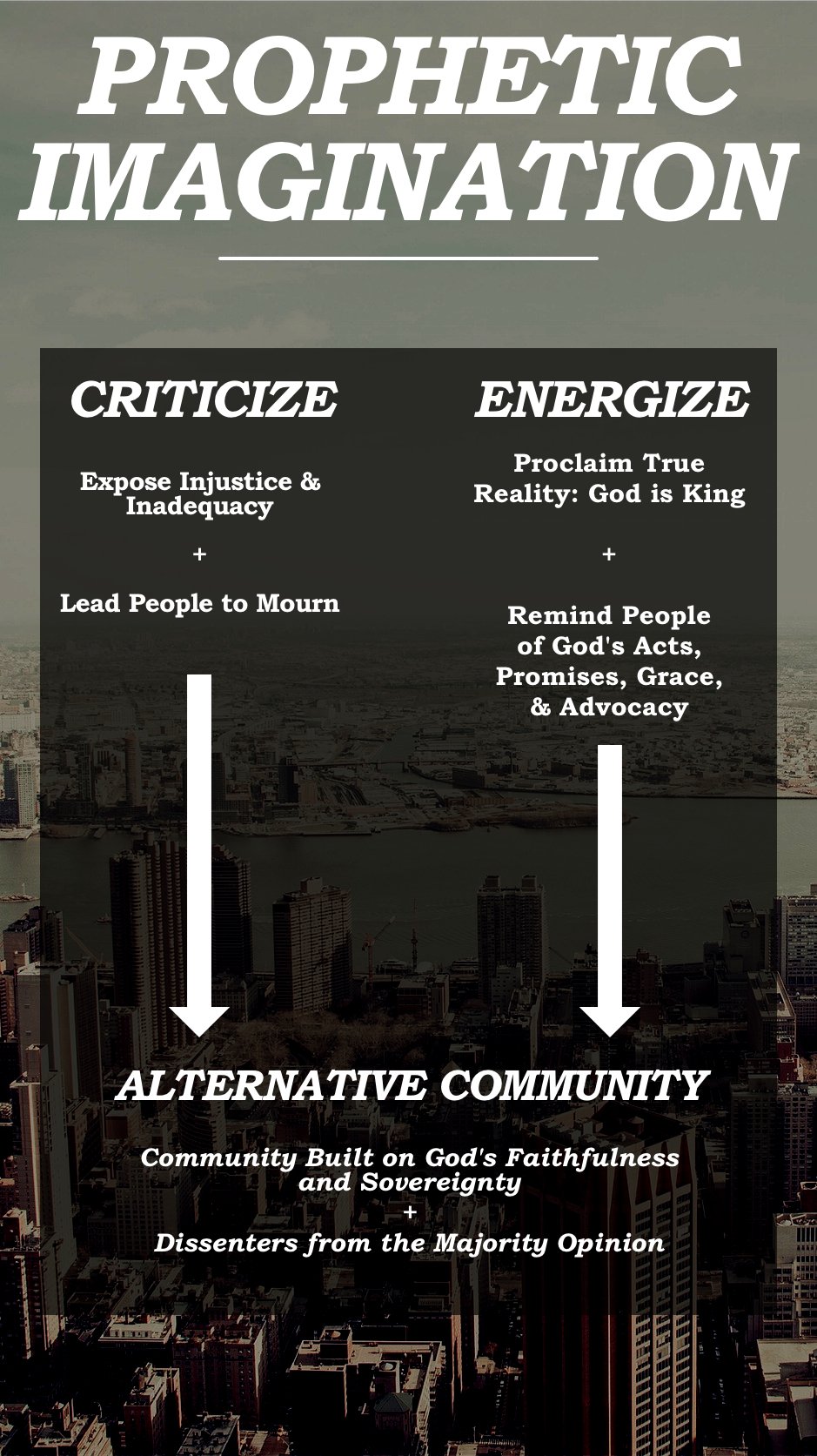

So he writes The Prophetic Imagination. His argument is rather straightforward: “The task of prophetic ministry is to nurture, nourish, and evoke a consciousness and perception alternative to the consciousness and perception of the dominant culture around us” (3). Prophets did not walk around just telling the future, nor did they just confront kings or set-up soup kitchens. They instead pointed people past the culture around them, exposing the lies of the rulers of the land, helping people see the world the way the God of Israel saw the world. The future they described was God’s end goal for humankind, and that future imposed on the present; God’s truth led them to denounce corruption, lead a life that played by different rules, and speak of something new on the horizon. This was the job of a prophet.

Brueggemann’s foundational example is Moses. The great prophet of the Torah is the human God works through to establish Israel. Yes, Israel had a tradition and identity that dated back to Abraham, but it was not yet a distinct and separate entity on its own. It was instead a part of Pharaoh’s empire; Israel existed merely as a wheel in the machinery of the oppressive tyranny of Egypt. In this context, Moses begins his prophetic ministry. The God that Moses preaches is free from the oppression and control that Pharaoh tries to lord over the earth. God is the radical alternative to Pharaoh, radical because he actually is God and King, radical because he is concerned with justice instead of tyrannical order. Pharaoh tries to keep his machinery moving by insisting that things are according to the will of the gods, that there is no hope for a different scenario, that there is enough food to take his subject’s minds off of how ill-used they are. Moses comes to shatter this lie: God has heard the cry of Israel, and will break the propaganda-induced numbness of Pharaoh like a twig.

Moses’ job has two parts:

-

Criticize the empire of Pharaoh and expose its corruption.

-

Energize the people of God to embrace a new mode of living.

These two parts are crucial; the energizing into God’s true reality can’t happen until the people see the falseness in the empire’s description of reality, and the criticizing by itself will leave people left in despair of their situation. As Moses does this—in combination with God showing up in a mighty way—a new community is formed, one with an alternative way of life: equality among people, economics based on communal survival and well-being, and doxology of God instead of Pharaoh.

Eventually, however, the monarchs of Israel fall into the same pattern as Pharaoh. Things revolve around them instead of God, and they will oppress whoever necessary to get their way. The prophets show up again to speak against the kings, show that their ways were killing their world, and lead people to mourn Jerusalem as a failure, as idolatrous. The prophets of the exile renew the people with hope in God’s grace and promises of a new Jerusalem, but mourning comes first.

Criticizing, energizing, and forming an alternative community: this process has to be repeated constantly, but this is what the prophets are all about.

And, says Brueggemann, this was also part of what Jesus was about.

Jesus was, of course, more than a prophet, but he also acted in continuity with the Jesus shows up and sides with the poor and oppressed, criticizing the rulers—political, religious, economic—in his ministry that breaks down their stranglehold on the people. His crucifixion is “the ultimate act of prophetic criticism in which Jesus announces the end of a world of death… and takes the death into his own person” (95). The Christ stands with the oppressed by taking on the ultimate oppression.

His prophetic energizing, however, is in his resurrection. The healings, miracles, and exorcisms were part of that energizing—all were acts that gave life where life was stifled or gone—but the resurrection shows how powerless the ultimate weapon of the dominant culture is. In this—his empty tomb that is a promise of his followers’ own—the greatest hope that God gives is realized. This is not optimism that the world will get better, but the promise of God that corruption and oppression cannot and will not win. The alternative community finds itself singing God’s praise while standing on his promises as the true foundation of reality.

So where does this leave us? Do Brueggemann’s thoughts leave the page and seep into our lives as Christians?

There is much here to ponder—and I can’t fit all his thoughts and arguments into a single blog post—and much in this summary that can help us as we approach the prophetic books. Brueggemann gives us a frame on which to stretch the prophetic canvas; we see a more complete picture of what the prophets were up to as they went about God’s business. This wasn’t vague fortune-telling or flimsy relief work, but the breaking down of barriers and the breathing of new life into despairing people. The people of God emerge from this effort as a community of justice, hope, and righteous praise.

We also see the continuity that Jesus had with the prophets. We cannot reduce Jesus to simply a prophet—we still understand him as the Second Person of the Trinity—but here we see him in a light that amplifies his love for justice and compassion for those who cannot defend themselves. Perhaps most importantly, we are reminded that we as the church are born from the Cross and the Resurrection; we are meant to be the alternative community born from this radical vision of Christ. A lack of understanding the prophetic side of Jesus’ ministry leads us to offer “crossless good news and a future well-being without present anguish” (44). Jesus’ prophetic imagination is part of what makes the Gospel good news in the first place, and we cannot be the church without it.

Next week will kick off reflections on Brueggemann’s Theology of the Old Testament.

Reed Metcalf works as a Media Relations and Communications Specialist at Fuller Theological Seminary. He writes for and curates the Fuller Blog and contributes regularly to FULLER magazine. He graduated with his MDiv from Fuller in 2014 and is an ordination candidate in the Free Methodist church. When not neck deep in biblical languages, theology, and writing, Reed is often surfing, skating, or hiking with his wife Monica.

You can follow Fuller Seminary on Twitter at @fullerseminary.