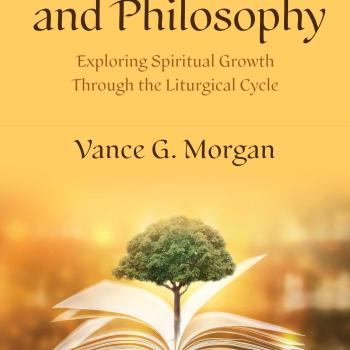

I’m back! After a two week break it’s good to be blogging again. As I continue to put my book A Year of Faith and Philosophy into final shape, I find that I’m doing some new writing in addition to editing and reorganizing. Here’s what I wrote for one of the later Sundays in Ordinary Time.

In the Ordinary Time 18 Year B reading from Mark 9, Jesus returns to his lesson that the last will be first in response to the disciples bickering about which of them will be the greatest in the kingdom of God. He illustrates the point by picking up a child and saying, “Whoever welcomes one such child in my name welcomes me, and whoever welcomes me welcomes not me but the one who sent me.”

This is one of the few times we see Jesus interacting with children in the gospels. We know little about the lives of any of the disciples, including whether any of them had children, but in the next chapter it is clear that they believe Jesus has far more important things to do than hanging out with kids. As people bring their children to Jesus for a blessing, the disciples turn them away. Jesus is not amused.

Let the little children come to me; do not stop them; for it is to such as these that the kingdom of God belongs. Truly I tell you, whoever does not receive the kingdom of God as a little child will never enter it.

Artist’s renditions of this scene invariably depict Jesus sitting on a rock with a half dozen innocent looking children around 3-5 years old gathered around him. Jesus usually is holding in his lap the youngest of the children who is reaching up with a chubby hand to touch Jesus’ beard.

What might it mean to receive the kingdom of God as a little child? A typical interpretation is that we must turn to God with the innocence of a child—unquestioning, accepting, vulnerable, and passive. Yet anyone who has ever spent time with a small child or even an infant for more than a few minutes knows that this is a romanticized and surface level picture. Children are far more interesting and complicated than can be captured by “innocent.”

Augustine of Hippo, the fourth century theologian and philosopher who is second only to the Apostle Paul in his influence on the development of early Christian doctrine and belief, spends a good deal of time at the beginning of his classic Confessions pushing back against the popular myth that infants are innocent creatures. Confessions is a classic story of conversion; Augustine spends the first half of the book convincing the reader that he (and therefore we) are self-centered and power hungry, steeped in sin, from the moment we emerge from the womb. From his own observation of infants, Augustine imagines what he was like as an infant.

For an infant of that age, could it be reckoned good to use tears in trying to obtain what it would have been harmful to get, to be vehemently indignant at the refusals of free and older people . . . who would not yield to my whims, and to attempt to strike them and to do as much injury as possible?

As Hannah Arendt famously quipped, “Every generation, civilization is invaded by tiny barbarians—we call them ‘children.’”

Aristotle opened one of his magisterial books with the observation that “philosophy begins in wonder”—a natural capacity that all human beings are born with and that we lose in short order under the pressures of conformity, education, and constant demands of behavior and belief. I often tell students in my introductory classes that it is this capacity of wonder that I hope to reawaken in each of them. Wonder is what a baby shows with her frank and forthright way of gazing about in bewilderment, trying to balance her oversized head on her undersized neck as she wonders “What’s this thing? And what’s that over there? And good God what’s THAT??” An inexhaustible openness to everything, an amazement in which nothing is mundane and everything is new.

It is this sense of amazement and wonder that Jesus has in mind when he says that we must receive the kingdom of God “as a little child.” The disciples (and we) are regularly confused and bewildered by what Jesus says concerning the kingdom of God because none of what he says makes sense when viewed through familiar and traditional lenses. Paul writes that “if anyone is in Christ, there is a new creation: everything old has passed away; see, everything has become new.” For the young child, there is no “everything old”—everything by definition is new.

The greatest source of wonder and amazement in the kingdom of God is that, despite our flaws, imperfections, self-obsession, and dark sides, we are the subjects of radical divine love. The first and greatest thing that a child needs to grow and thrive is an abundance of love, something each new human being has an unlimited capacity to receive. And in the kingdom of God, an unlimited supply of unconditional love is available.

For reflection: What are the characteristics of your inner child that make it possible to receive the kingdom of heaven?