I’ve spent significant time over the past fourteen or fifteen months immersed in the Bible. I’ve often said and written that I was brainwashed in the Bible as a youth, so I’ll put my knowledge of and familiarity with scripture up against most anyone’s (except those whose job it is to be buried in the Bible all the time (priests, pastors, theologians, etc.).

But this is different. I began assembling material for a book tentatively called A Freelance Christian’s Guide to the Liturgical Year in May 2023 at the beginning of my sabbatical. That same book, now titled A Year of Faith and Philosophy: Exploring Spiritual Growth Through the Liturgical Year (there was another title between the first and final one) is on its way to my editor tomorrow. The scripture index is five pages long–I’ve spent so much time in the gospels particularly that I feel as if Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John have been sitting in our library room with me having a beer or bourbon while fact checking what I was writing and reminiscing about the good old days.

One of my favorite passages from the gospels is from Matthew 22 when Jesus is asked “Which is the greatest commandment?” He memorably answers,

You shall hold correct beliefs about the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind. This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: You shall convert your neighbors who do not hold correct beliefs, and if they will not convert, you shall defeat them in a culture war. On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.

And remember the following from First John?

Beloved, let us hold to correct beliefs, because correctness is from God; everyone who believes the required statements is born of God and knows God. Whoever does not confess the right beliefs does not know God, for God is correctness.

And this?

Those who say, “I love God,” and hold incorrect beliefs are liars; for those who do not express correct beliefs that they can capture in words, cannot love God whom they cannot capture in words. The commandment we have from him is this: those who love God must have the correct beliefs about God.

“Wait a minute!” you say. That’s not what Jesus said! That’s not in First John! You’re right—but many Christians use doctrine and orthodoxy so rigorously as measures of each other’s faith that one might imagine that the above is actually in Scripture. The true passages misquoted above focus exclusively on the centrality of love to the life of faith, but you’d never know it when observing the ways in which many Christians judge and exclude each other.

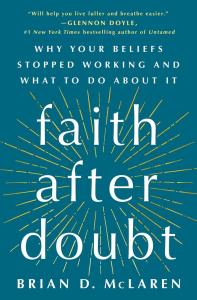

The creative misquotes of scripture above are from Brian McLaren’s 2021 book Faith After Doubt. McLaren has been a pioneer in the process of deconstructing one’s faith, of dismantling aspects of one’s belief framework in the interest of making creating new wineskins to contain and shape the ever-changing features of a faith that never stops evolving, for several decades.

McLaren reports that a few years ago, during the Q and A following one of the many talks that he has given across the globe, a clearly frustrated man stood up and angrily asked “Who do you think you are to make up your own doctrines and create your own version of Christianity? Why don’t you just admit you’re a heretic and stop calling yourself Christian?”

In my own small way I know what it’s like to be the receiver of pushback and vitriol such as this. The most negative and incensed comments I have received on this blog have not come from atheists or non-Christians. They have come from Christians who don’t appreciate seeing their favored religious framework get questioned, challenged, or (most egregiously) poked fun at. I’d love to have a dollar for every time I’ve been condemned to hell, called a heretic, or worse because something I wrote didn’t fit into someone’s box very .

Although I laughed it off at the time, a friend’s report not long ago that one of our colleagues believes I have denied the resurrection in this blog clearly stuck with me. It was time to take a step back and think about why my spiritual journey, which I track in this blog, and which has been a story of continuing change, adjustment, and evolution, has so often been a source of challenge and outright scandal to many—particularly those who live in traditional frameworks of faith that I no longer inhabit.

Consider the Resurrection, for instance, since that’s what I have apparently been accused of denying. As with any historical event in the past, we do not know exactly what happened on that day. Where I have gotten into trouble frequently is not by saying that Jesus did not rise from the dead (I believe that did happen) but rather by saying that the truth of the Resurrection is not locked into historical details that we cannot possibly confirm or deny. Rather, the truth of the Resurrection transcends historical facts, and the meaning of that truth expands and evolves.

Brian McLaren writes that as one’s faith grows and changes, “old beliefs begin to shine again, but in fresh ways.” The Resurrection becomes “not a single resuscitation alone, but the uprising of a whole new humanity, filled with the Spirit of the risen Christ to be the ongoing embodiment of God-with-us.” The Incarnation expands so that it is “not [just] a one-time exceptional event, but [is] as a window into God’s inter-being with all of us and even all of creation,” something that sounds very similar to my understanding of the Incarnation as the astounding truth that God chose to engage with the world in human form and continues to choose human beings as the way the divine gets into the world–a central theme of my new book, by the way.

Toward the end of Faith After Doubt, McLaren reflects on the difference between insisting that the stories of the faith and scripture are factually true as he (and I) was taught to believe that they were in his youth, and what those stories mean to him now in his middle-sixties.

What mattered most was not that I believed the stories in a factual sense, but that I believed in the meaning they carried so I could act upon that meaning and embody it in my life., to let that meaning breathe in me, animate me, fill me. . . Whether I considered the stories factually accurate was never the point; what actually mattered all along was whether I lived a life pregnant with the meaning those stories contained. To my surprise, when I was given permission to doubt the factuality of my beliefs, I discovered their actual life-giving power.

Friedrich Nietzsche’s infamous claim that “God is dead” is an expression of his observation that there is a great difference between believing that God exists and believing in God. The former is an intellectual assent that frequently makes no difference in one’s lived experience. The latter is what McLaren is describing. Nietzsche further observed that in his late 19th century European world, many people both paid verbal assent to God’s existence and lived their lives as if it didn’t matter. The word “God,” in other words, had lost its meaning for such people. Hence for all intents and purposes, for those people “God is dead.”

A vibrant and life-changing faith does not depend on whether the details of the stories the faith is rooted in are literally or factually true. Such a faith depends on the ways in which the messages of those stories make a difference in one’s life, empowered by divine energy. As Paul writes, “the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life.”