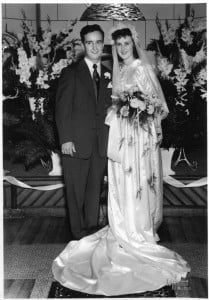

Thirty-six years ago today, two early thirty-somethings stood in front of their four parents and exchanged promises; the groom’s father was an ordained minister, so the promises exchanged were official. It was a quickly organized, impromptu event because the groom’s mother was dying of cancer and might not live to experience the real, full-blown wedding planned for a year or so down the road.

That wedding never happened. The groom’s mother died less than three months later, followed unexpectedly by the bride’s father dying a couple of weeks later. I don’t remember what either Jeanne or I said in our exchanged promises that hot July day in Pennsylvania. But looking back from the distance of thirty-six years, perhaps someone should have said something like this:

Love is a painful, poignant, touching attempt by two flawed individuals to try and meet each other’s needs in situations of gross uncertainty and ignorance about who they are and who the other person is, but we’re going to do our best.

Or this:

Marriage is a hopeful, generous, infinitely kind gamble taken by two people who don’t know yet who they are or who the other might be, binding themselves to a future they cannot conceive of and have carefully avoided investigating.

These definitions of “love” and “marriage” are from Alain de Botton in a conversation on Krista Tippett’s program “On Being” in 2017 called “The True Hard Work of Love and Relationships.” They strike me as accurate, which is probably why de Botton doesn’t get asked to offer comments or propose toasts at weddings very often.

I have never thought of my parents as a love story—they were my parents, for God’s sake. But it occurs to me that Jeanne and I are now more than a decade older than my father was when my mother died. I understand so much better now than I did thirty-six years ago at least some of what he must have gone through, since I have no doubt that he expected he and my mother would see their fiftieth wedding anniversary (they made it to their twenty-seventh) and live together into their eighties as both his parents and my mother’s parents had done.

For years Jeanne and I have had a good-natured disagreement about which of us is going to die first—neither of us wants to outlast the other. I can’t imagine life without the person with whom I have for better and for worse spent more than half of my years. My anniversary wish is what the author of the Book of Tobit asks: Mercifully grant that we may grow old together.

George Eliot uses this epigram to introduce one of the late chapters in her masterpiece Middlemarch, my favorite novel to which I returned when reading Rebecca Mead’s My Life in Middlemarch a while ago. Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot was her nom de plume) lived a scandalous life by the standards of Victorian England, but I was amazed to see how many similarities there are between Jeanne’s and my relationship and Mary Ann’s relationship with the love of her life, George Henry Lewes. Mary Ann and George (Evans took her writing first name from Lewes) met in their early thirties, as Jeanne and I did.

When we met, Jeanne had never been married, while I had been divorced five months earlier; when she met Lewes, Evans had never been married, while Lewes was still married to his estranged wife who after their separation had four children with another man (due to the technicalities of British law, they were never divorced). I had two sons in tow when Jeanne and I met; Lewes had three sons in their teens when he and Mary Ann met, all of whom were at boarding school. To the great scandal of Victorian society, Evans and Lewes lived together openly without marrying for more than two decades in what appears to have been a very happy and fulfilling relationship.

I loved reading Rebecca Mead’s chapter on Mary Ann and George’s relationship because so much of it sounded familiar. To use an overused term, they were clearly soulmates; if the word means anything at all, it describes Jeanne and me as well. In an essay written while she was on her “honeymoon” in Germany with Lewes, Mary Ann wrote that

It is undeniable that unions formed in the maturity of thought and feeling, and grounded only on inherent fitness and mutual attraction, tend to bring people into more intelligent sympathy with each other,

while in a letter to a friend later in life she wrote that

To be constantly lovingly grateful for the gift of a perfect love is the best illumination of one’s mind to all the possible good there may be in store for man on this troublous little planet.

During a rough patch many years ago, a dear and trusted friend who since has died told me that Jeanne and I are “home for each other.” We are. It sounds as if Mary Ann and George were home for each other as well.

A few years ago I had an interesting conversation with a friend from church who mentioned something that she and her husband happened to share with Jeanne and me. For the first time in thirty-five years of marriage, this couple had just started living in their house by themselves—no children, no guests, no long-term tenants. Similarly, Jeanne and I were in the first few months of it just being the two of us in our house—no children, no long-term guests. After years of not seeing each other for weeks at a time when Jeanne was travelling constantly for work, all of a sudden we were in each other’s space all the time (and continue to be).

“Has it been really hard?” my friend asked, silently implying that it had definitely been a challenge for her and her husband. I could truthfully say that while it was certainly different, it was not hard at all, except when I am continually trying to go to some location in our small house at the same time that Jeanne wants to get there. Why are we always both in our little kitchen at the same time? We have a quiet, normal life of the sort that those who only know the extroverted side of Jeanne would find hard to believe. Ours is not the sort of love story that people write novels or make movies about—there’s too much of the everyday and too little blockbuster drama to hold a viewer’s attention.

Toward the end of Rachel Kadish’s Tolstoy Lied, the main character reflects on what she has learned about love.

Toward the end of Rachel Kadish’s Tolstoy Lied, the main character reflects on what she has learned about love.

Love–real love–is not cinematic. It’s the stuff no one talks about: How trust grows rootlets. How two people who start as lovers become custodians of each other’s well-being.

On our anniversary, I am grateful beyond measure that I met this beautiful redhead at my parent’s house almost thirty-seven years ago (!)—it is more than I could have hoped for and more than I deserve. There is one way in which I do not wish Jeanne’s and my relationship to be like Mary Ann and George’s. They both died at age 61; we are now several years older than that. And so I ask, mercifully grant that we may grow old together.