The first time someone told me they believed slavery was a Biblical precedent I was just beginning a career in the anti-trafficking movement, and we were watching the film Amazing Grace, which tells the story of William Wilberforce and the historical abolitionist movement. I was appalled—and immediately went into fight mode.

Yet as this individual pointed out that slavery was even in the New Testament, referring to the Roman household codes, I began questioning myself. What if I was wrong? Could slavery be Biblical after all?

Although most American Christians today would say slavery is wrong, many don’t have a strong theology around it. Even though anti-slavery and anti-exploitation efforts—now called anti-human trafficking—are among the justice issues evangelical Christians tend to support, their understanding can be easily shaken. That’s why I believe it’s important we explore a Christian theology on slavery today more deeply.

Why Christians Are Hesitant to Act Against Slavery Today

I’ve been working in anti-trafficking for over twenty years. The first organization I founded served as a funnel between local nonprofits and government entities, allowing churches to provide funding, volunteers, and education. Even though our local congressman specifically asked churches to lead the way in anti-trafficking work and urged citizens to get involved, it was difficult to convince pastors to see this as a priority worth mobilizing their congregations around.

Over time, I learned there are two primary reasons Christians hesitate to engage with ending slavery today:

- They don’t recognize modern slavery for what it is.

Many assume slavery ended with the Civil War. I’d have to educate Christians that trafficking victims are indeed slaves—either being sold sexually or forced to work without pay–with force, fraud, or coercion used against them. I had to challenge the idea that women in the sex trade were there by choice and show that many were controlled by traffickers (or “pimps”). I asked people to consider whether those who labor to make our products under unjust conditions, without a living wage, should also be viewed as slaves.

Raising this awareness could be exhausting—but necessary. Twenty years later, although many more people at least know the term “human trafficking,” many others still don’t know what it means.

- They don’t understand the full Biblical narrative.

Many people pull isolated verses—like the individual who gave me his opinion during that movie night—without understanding the overarching story of Scripture. Slaveowners throughout history have used the same approach. How do we counteract it? By looking at the whole biblical narrative.

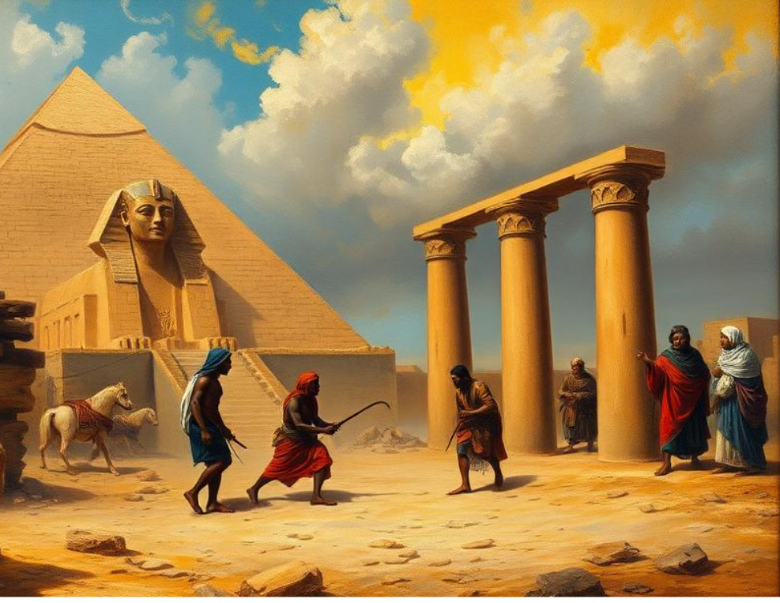

Slavery in the Old Testament

First, it should be noted that slavery did exist in the Old Testament. It was legal under Mosaic law. But even here, we see glimpses of God’s concern for the vulnerable:

- Hagar, who fled her enslavement, was met by God in the wilderness—twice—with provision and promise (Genesis 16, 21). Although the first time she was told to go back, the second she wasn’t. (Read more on this story here.)

- The young Israelite girl in Naaman’s household was used by God to bring healing to her master, revealing God’s power even through the enslaved (2 Kings 5). Why did she care enough for him to bring him hope? Was her life changed because of his newfound belief?

Also, we cannot forget that the entire Hebrew narrative is based on the experience of being freed from slavery in Egypt (Exodus). This foundational story frames slavery as something to be set free from—not perpetuated.

The Mosaic Law included regulations that protected enslaved people. Here are a few:

- Slaves were to be released after seven years (Exodus 21:2).

- A slave could choose to stay with a family they had bonded with for life because the relationship was loving and mutually beneficial (Deuteronomy 15:16).

- Israelites were frequently reminded, “Remember that you were slaves in Egypt…” (Deuteronomy 5:15).

While slavery under this system might seem terrible, and there are some Levitical laws I find myself frustrated at, we need to understand that brutal chattel slavery that we see in American history wasn’t what was allowed. There were relational and legal dynamics that provided for much more human dignity.

The New Testament: A Shift in Perspective

Jesus declared that he came “to proclaim freedom for the prisoners and recovery of sight for the blind, to set the oppressed free” (Luke 4:18). Many assume this was only spiritual, especially as we don’t see Jesus going around setting slaves free. But ultimately, the Gospel sets a trajectory for both spiritual and physical liberation.

For example, in Paul’s letters (Ephesians 6:5–9, Colossians 3:22–4:1), the Roman household codes are reinterpreted. Paul doesn’t outright condemn slavery, but he reframes the relationship between master and servant into one based on mutual love and accountability to God. This shifts this relationship drastically without tearing down a system that most Christians were powerless to tear down within that time and age. These ensured that oppression was to be eschewed by the Christians.

In Philemon, Paul writes to a Christian slaveholder, asking him to receive his runaway slave, Onesimus, back “no longer as a slave, but better than a slave, as a dear brother” (Philemon 1:16). This is a powerful example of the Gospel reordering human relationships.

Slavery and the Early Church

Many early Christians were slaves themselves. The New Testament includes guidance for them—not to endorse slavery, but to give hope and dignity within an unjust system (1 Peter 2:18–25).

Over time, Christian masters became known for treating their slaves with uncommon kindness. The social and economic structures were complex; setting a slave free did not often lead to better living conditions. But gradually, a distinct Christian ethic emerged that moved away not just from ownership and and some did begin to set their slaves free. Christian leaders like Gregory of Nyssa in the fourth century began openly denouncing slavery as a violation of God’s design. This moral belief laid the groundwork for future abolitionist movements.

Democracy and Slavery: Conflicting Values

I don’t believe democracy is perfect, nor do I think it always reflects or is designed to Christian values. But democracy is intended to value freedom and individual human rights, which are inherently incompatible with slavery. Our experience with democracy can be a helpful lens to see this incompatibility in God’s Kingdom, too.

I used to visit Mount Vernon often when I lived in Virginia. One museum exhibit described how George Washington arranged for his slaves to be freed, a decision his wife Martha carried out after his death. While he never publicly tied this decision to his faith, his personal writings reveal discomfort with slavery’s moral implications.

Other abolitionists—like William Wilberforce, Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and even Thomas Jefferson (despite his own contradictions)—spoke of the hypocrisy of slavery’s with the Christian faith and their values of democracy.

More Than a Moral Imperative

The primary way slavery appears in the New Testament is not as a social issue, but as a spiritual metaphor:

- We are “slaves to sin” but are set free in Christ (Romans 6:6).

- We are called to be “slaves of righteousness” and “servants of Christ” (Romans 6:18, Ephesians 6:6).

This paradox reminds us that true freedom isn’t found in self-serving and being in bondage to things like money, anxiety, lusts, etc…but it is found in surrender to God’s will, who we can trust knows what is best for us. This is hard for many of us, but “Lordship” is an essential part of the Christian faith.

In Luke 18:18–25, Jesus tells the rich ruler to sell everything and follow him—an invitation to let go of control and choose spiritual freedom. But in doing so, he would inadvertently care for others. As we make Jesus our Lord, our eyes open to the needs of others.

In his case, a rich man would care for the poor. In ours, we who are free will seek the freedom of others. We who are powerful will use our influence to uplift the oppressed.

In the New Testament, a version of this statement shows up frequently:

“There is no longer Jew or Gentile, slave or free, male and female. For you are all one in Christ Jesus.”

— Galatians 3:28 (NLT)

When we live this out, it flattens hierarchies like slavery. We can’t help but seek the good of others. When we live out this Gospel truth, viewing other believers as brothers and sisters, we cannot participate in systems that degrade others.

Today’s anti-trafficking movement—like the abolitionist movement of centuries past—are often led by people of faith. Slavery is not God’s design, something that becomes evident as we understand the full arc of Scripture. Freedom—both spiritual and physical—is not just a biblical imperative. Freedom is the foundation of human flourishing, community, and joy.