The first time I saw Darren Aronofsky’s Noah, I took six pages of notes, and I watched it with the memory of an early draft of the screenplay lingering in my brain. So I was distracted on at least two levels: by a need to jot down as many quotes and facts as I could, and by an awareness of how the script had evolved. Never mind people who obsess over how the film may or may not have deviated from Genesis; I kept thinking of how the film was deviating from that early script!

The first time I saw Darren Aronofsky’s Noah, I took six pages of notes, and I watched it with the memory of an early draft of the screenplay lingering in my brain. So I was distracted on at least two levels: by a need to jot down as many quotes and facts as I could, and by an awareness of how the script had evolved. Never mind people who obsess over how the film may or may not have deviated from Genesis; I kept thinking of how the film was deviating from that early script!

Needless to say, I don’t normally take that kind of background knowledge to the theatre when I go to see a movie, and I knew it wouldn’t be fair to Noah to hold that knowledge against it either. I also knew I needed to just sit back and watch the movie like a proper movie, to bask in the drama and let it unfold.

And so, on Wednesday morning, I saw the film a second time. And I can think of no better way to sum up the difference between my two viewings of the film than to say that I didn’t cry at all the first time I saw Noah, but I shed tears on a few separate occasions the second time I saw it. It’s a powerful, powerful film.

Not everyone thinks so, of course. A variety of things prevented me from finishing this blog post until today, and as it sat half-written on my computer, the film came out in theatres and was seen by a lot of people — and a number of them (including people I consider “friends”, at least in the Facebook sense) proceeded to write some of the most blistering screeds imaginable against not just the film, but against “lying” “tools” such as myself and other Christians who had said positive things about the film.

It’s one thing to have a difference of taste or opinion. It is also quite possible that my take on a film will change from one viewing to another, and I might wonder what I was thinking the first time I saw it; that was certainly my experience with, say, Kingdom of Heaven, which got worse for me the second time ’round. But to accuse people like me of being “self-loathing” liars is just something else entirely.

Noah is not a perfect film by any stretch. It has plot holes and it is weak on some of the key themes in Genesis. And Noah is certainly not a film for everybody; I can’t think of a single Aronofsky film that even tries to be all things to all people.

Noah is not a perfect film by any stretch. It has plot holes and it is weak on some of the key themes in Genesis. And Noah is certainly not a film for everybody; I can’t think of a single Aronofsky film that even tries to be all things to all people.

But it just so happens to be the kind of film that taps into a few of my favorite subjects, from obscure Bible history and ancient mythology to the science-and-religion debate, and it is made by someone who has been passionate about this project for years and knows how to talk about it knowledgeably — so on whatever level I may love this film, my love is true.

Will I feel differently if I see the film a third time? Quite possibly. Who knows. I’ll cross that bridge when I get to it. For now I’m listening to Clint Mansell’s soundtrack album a fair bit and reliving the moments I want to relive through the power of music.

So, back to the film and my deepened emotional reaction to it when I saw it last Wednesday. What is the source of the film’s power? I can think of at least two things.

First, there is the family drama.

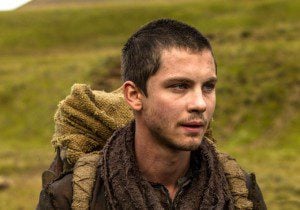

After a prologue that takes place when Noah is a boy, we meet him as an adult who is living by himself with a wife and three young sons, ranging from newborn Japheth to the approximately ten-year-old Shem. And then, after a certain point, we jump ahead in time about ten years, and we find that Shem is an adult, in an adult relationship with Noah’s adopted daughter Ila, while Noah’s middle son Ham is also in his late teens at least, and is certainly on the cusp of becoming a man himself.

And in the childhood scenes, we see the seeds of who these children grow up to be. Shem gets along extremely well with his father; Ham, not so much.

When Ham is young, the relationship doesn’t seem all that strained yet, an incident in which Noah chides Ham for plucking a flower needlessly notwithstanding. But by the time Ham is older, we can see how he may have come to resent the preferential treatment that Noah has given his older and younger brothers. It’s classic middle-child stuff. And the fact that Shem has a significant other in Ila, when Ham has no one to call his own, just makes it worse.

When Ham is young, the relationship doesn’t seem all that strained yet, an incident in which Noah chides Ham for plucking a flower needlessly notwithstanding. But by the time Ham is older, we can see how he may have come to resent the preferential treatment that Noah has given his older and younger brothers. It’s classic middle-child stuff. And the fact that Shem has a significant other in Ila, when Ham has no one to call his own, just makes it worse.

Something that really struck me on this second viewing was how we see the young Ham playing with one of the Watchers (i.e. one of the fallen-angel “rock giants”).

As Noah and Shem return from their visit to Methuselah’s mountain, we see Ham run around the Watcher who escorted Noah’s family there. “You can’t get me!” shouts Ham playfully, and I suddenly felt sad for this boy, knowing how tortured his relationship with his father would become, and knowing that the Watcher he had befriended would one day die, either in the Flood itself or at some point before, and leave him behind.

I was also struck by the fact that the two main visions Noah has — the visions that tell him there’s a Flood coming, and what to do about it — were precipitated by scenes in which members of his family care for him or guide him in some way.

The first vision begins when Noah is asleep in his tent with his family. Naameh, his wife, strokes his face and soothes him to sleep, and it is after this that Noah has the first of his frightening, harrowing visions. The second vision begins when Noah visits his grandfather Methuselah for the first time in years (since before Noah had children, possibly), and Methuselah gives him a sort of hallucinogenic tea, which facilitates a vision in which Noah sees the Ark floating in the water, and animals swimming up towards it.

Then there is Noah’s relationship with Ila, which in many ways is the heart of the story. I can’t say much without getting into specific plot points, but suffice it to say that Noah and Ila have a few scenes together that really work. In one scene, Ila makes a tearful, self-sacrificial request that prompts Noah to assure her of her place in his family; and in another scene, much much later, it is Ila who assures Noah that he still has a place in his family, too.

Then there is Noah’s relationship with Ila, which in many ways is the heart of the story. I can’t say much without getting into specific plot points, but suffice it to say that Noah and Ila have a few scenes together that really work. In one scene, Ila makes a tearful, self-sacrificial request that prompts Noah to assure her of her place in his family; and in another scene, much much later, it is Ila who assures Noah that he still has a place in his family, too.

And in between those two scenes… well, let’s just say things get a bit crazy.

The second reason this film is so powerful, for me at least, is that it gets at everything that can be so appealing and appalling about religious faith.

On the appealing side: the sense of wonder, the love for creation, the conviction that right and wrong matter, and the hope that God will make things right again. On the appalling side: the sense of dread, the fear of judgment, the feeling of alienation when God does not answer prayers as clearly or quickly as you would like, and the fact that the community you turn to for strength can sometimes turn against you.

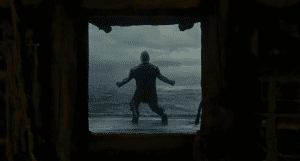

The Noah of this film is a decent man, hardened perhaps by the fact that he has had to keep his family safe from all the wickedness around them. His initial visions, and his interpretations of them, are utterly vindicated by the miracles that follow, not least the orderly arrival of all the animals and the Flood that strikes when the animals are all safely aboard the Ark. What’s more, Noah does not let his divine task go to his head; he sees himself entirely as a servant of God, and as a steward of God’s creation. There is no attempt to exploit the situation for his own benefit. He puts himself utterly at God’s service and is, quite frankly, someone to emulate in these areas.

But at times his interpretations of God’s will seem to go too far. Even though God has spared Noah’s family aboard the Ark just as he spared a representative sampling of the animals, Noah comes to believe that humanity should die out completely. This means not even trying to help people when they plead for help outside the Ark. And eventually this means that, when Ila herself becomes pregnant, Noah becomes convinced that he should kill her child — at least if the child is a girl and therefore capable of bearing even more children.

But at times his interpretations of God’s will seem to go too far. Even though God has spared Noah’s family aboard the Ark just as he spared a representative sampling of the animals, Noah comes to believe that humanity should die out completely. This means not even trying to help people when they plead for help outside the Ark. And eventually this means that, when Ila herself becomes pregnant, Noah becomes convinced that he should kill her child — at least if the child is a girl and therefore capable of bearing even more children.

And so, in this regard at least, Noah becomes the sort of spiritually, psychologically and even physically abusive parent that one finds in some religious families. And his abusiveness is made all the worse by the fact that his faith is utterly sincere, and not a cynical cover for a generally wretched personality.

But the very qualities that signified Noah’s goodness are not that far removed from the qualities that bring out his dark side.

His isolation from wicked human society, which initially kept him and his family safe, only intensifies when the wicked society is destroyed, and it leaves his offspring with nowhere to hide from his own homicidal intentions. The Ark that protected Ila and the others from God’s wrath becomes a trap within which they cannot get away from God’s servant. And the selflessness and sincerity that were signs of Noah’s goodness earlier in the film have now been twisted into something wrong.

Some people have objected to the idea that Noah turns its protagonist into a “religious zealot”. But one of the things I value about the film is the way it explores both the good and bad sides of that zeal. Its treatment of that zeal is ambivalent, neither wholly positive nor wholly critical, and it leaves us with a lot to think about.

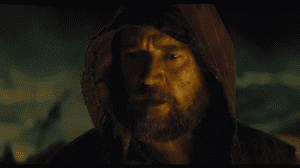

I have to pause a moment here to praise Russell Crowe’s performance in this film.

I have to pause a moment here to praise Russell Crowe’s performance in this film.

I said almost nothing about the actors in my earlier post on this film, and that was an oversight. I absolutely love the tenderness with which Crowe’s Noah speaks to Ila when he tells her that she was a “precious gift” to his family, and I absolutely love the anguish in his voice when he finds out that Ila is pregnant; you really feel his trauma — you can sense how haunted he is by all the death he has witnessed — when he says “All those people!” may have died “For nothing!” if Ila goes on to perpetuate the human race.

There aren’t many actors who could capture both the loving-parent side of Noah and the homicidal-zealot side of Noah with such complexity and conviction, but Crowe does it. You really feel for the guy. And you completely understand why Noah ends up drunk and naked on a beach at the end of it all, wondering whether everything he went through was really worth it.

I want to turn for a moment to the question of how Noah gets his messages from God.

In the Bible, God seems to speak to Noah with words. But in the film, God communicates with visions (and Aronofsky suggested in his recent appearance on The Colbert Report that there may be a basis for this in the original Hebrew). The first two visions — the one that tells Noah there’s a Flood coming, and the one that tells him to build the Ark — come when Noah is asleep or at least somewhat unconscious.

But the third vision Noah has — the one that convinces him the human race should die out — is noticeably different.

For one thing, there is no clear break between the “real” world and the world of the vision this time. Instead, Noah goes to Tubal-Cain’s camp to see if he can find wives for his sons. While there, he witnesses the horrific treatment of both animals and people by Tubal-Cain’s men. And then he sees himself eating raw flesh like a savage. And then he sees fire come down from heaven and consume the camp.

Where is the line between reality and dream here? We are, no doubt, seeing what Noah sees in this scene. We are experiencing his state of mind. But is it reliable, as the other two visions were?

Where is the line between reality and dream here? We are, no doubt, seeing what Noah sees in this scene. We are experiencing his state of mind. But is it reliable, as the other two visions were?

Consider that final image of the fire. Noah knows that the judgment he is preparing for will come in the form of water, not fire; the film even underscores that the Flood is a very different kind of judgment than the one that Methuselah and his father Enoch were expecting. So why is there fire in this third vision? Does it reflect God’s intentions? Or does it reflect Noah’s own growing feelings about his own unworthiness, and the unworthiness of humanity in general, informed perhaps by the prophecies he heard from his ancestors when he was young?

Later, when Noah learns that Ila is pregnant, he begs God for a sign: not a sign telling him to kill his grandchild, but a sign that would tell him not to kill the grandchild. For some reason, he defaults to the assumption that infanticide is required of him. But this is not actually something that God told him to do.

As it happens, the rains stop falling after Noah promises that he will kill the child, at least if it is a girl. Noah interprets the rain’s end as a sign that God wants him to fulfill that promise. But Ila interprets it as the sign that Noah was asking for: a sign that he should not kill her child. Here there is no vision at all, just a possible sign that different people interpret differently.

Interestingly, when it turns out that Ila has actually given birth to twins, and Noah goes to carry out his death threat, Naameh tries to persuade him that the twins are, themselves, a sign: “You can’t kill two!” she says. “He sent us what we need!” Meaning, in this case, that God has sent them two wives for their two unmarried sons.

So, again, the final scenes boil down to a question of interpretation.

So, again, the final scenes boil down to a question of interpretation.

And the part of the film that some people find most problematic hinges on Noah “receiving” messages from God in a very different way than he received the earlier messages, so different in fact that it’s questionable whether God even sent the latter messages like Noah thinks he did.

Let’s see, what else was there…?

Oh, right, I was really struck by some of the repeated visual motifs.

I had forgotten just how often the film returns to a close-up of Cain’s hand holding the rock with which he is about to strike Abel dead. Whatever else one might say about this film’s view of mankind’s wickedness and how it ought to be defined, on a visual level, it keeps pointing back to the utterly biblical fact that one brother murdered another.

And then, near the climax of the film, this moment is echoed when Tubal-Cain raises a rock (or some similar object) in the exact same pose, with a similar intent to kill.

Also: the time-lapse imagery in the creation/evolution sequence is prefigured in another sequence that telescopes the ten years in which Noah and the Watchers build the Ark. And this prefiguring of the creation sequence works, on a thematic level, because the ten-year sequence starts with a magical forest that grew from a seed that can trace its roots, so to speak, back to Eden, i.e. back to Creation.

I also noticed this time that, in the prologue, when the young Tubal-Cain shows up looking for new mines to dig, his men are dragging a chained Watcher or two in the background. This moment foreshadows a reversal of sorts that comes much later, when the Watchers put chains around the Ark to protect it from Tubal-Cain’s men.

Other little details I liked: The glimpse of Pangaea during the opening credits. (That’s right, according to this film, humanity existed before continental drift!) The pssh! pssh! of the first raindrops landing on Tubal-Cain’s anvil. The final documentary-like scenes of animals with their young, after the Flood. (Methinks those animals are not CGI — though they also appear to have been filmed in their natural habitats, so no worries about trained animals here.)

Other little details I liked: The glimpse of Pangaea during the opening credits. (That’s right, according to this film, humanity existed before continental drift!) The pssh! pssh! of the first raindrops landing on Tubal-Cain’s anvil. The final documentary-like scenes of animals with their young, after the Flood. (Methinks those animals are not CGI — though they also appear to have been filmed in their natural habitats, so no worries about trained animals here.)

There are some plot holes and the like, but they tend to be the sort of plot holes that one can find in the Bible, so I’m inclined to go easy on the film in those areas.

For example, we could ask where Noah — supposedly the last of the line of Seth — finds his wife. (The filmmakers consciously avoided making her a descendant of Cain’s.) But then, we could also ask where the biblical Cain finds his wife.

The film also has a curious habit of jumping ahead in time and then almost forgetting that a lot of time has passed. When young Shem first meets Methuselah, they talk about berries. Then the film jumps ahead ten years and, the next time we see Methuselah, he’s still grumbling that Shem hasn’t brought him any berries. Really? After ten years? Neither Methuselah nor Shem visited the other again?

Similarly, the film jumps from the beginning of Ila’s pregnancy to the end, and we are left to assume that Tubal-Cain has been hiding in the reptile room for several months, biding his time. Maybe his wound took a very long time to heal, I don’t know.

A part of me does wish that Aronofsky had made a more complete adaptation of the early chapters of Genesis.

I do appreciate how he brings our attention to the fact that, biblically speaking, humans were not allowed to eat meat before the Flood — but God does permit the eating of meat after the Flood, and that’s missing here.

I do appreciate how he brings our attention to the fact that, biblically speaking, humans were not allowed to eat meat before the Flood — but God does permit the eating of meat after the Flood, and that’s missing here.

Also, even before the Flood, people like Abel were permitted to offer animal sacrifices, even if they did not actually eat the animals; it was, indeed, because God approved of Abel’s sacrifice and not Cain’s that Cain committed that first murder in the first place. But there are no sacrifices in Aronofsky’s film; instead, the closest thing we get to one is a scene in which Noah and his sons cremate an animal that has been killed by some poachers.

Of course, Bible movies always pick-and-choose the bits that suit the message that the filmmakers want to send.

The 1956 version of The Ten Commandments made a big deal of the Exodus, and of the liberation of the Hebrew slaves, but completely omitted the fact that the Hebrews themselves would go on to own slaves, and that the law of Moses would even give them permission to buy and sell slaves within certain parameters; that would have gone against the film’s Cold War message about “the birth of freedom”.

So if Aronofsky, who reportedly has vegan tendencies himself, wants to emphasize the part of the story that puts down meat-eating and not the part that permits it, or the part that embraces animal sacrifice, that’s par for the course.

Also, as my friend Steven D. Greydanus has noted, Aronofsky could have paid more attention to the significance of humanity being made in God’s image.

Aronofsky has written eloquently about the two creation stories in Genesis, and how they end with remarkably different directives that pull in opposite directions — but one of the key things about those stories is that they both present mankind as central to God’s Creation. In the first story, man is the crowning achievement, the cherry on top, the thing that makes Creation not just “good” but “very good”; and in the second story, God starts with man and makes everything else for man’s benefit.

There are hints of that in Aronofsky’s film — not least in the fact that Adam and Eve shine with the light of their unfallen state, different from all the creatures that came before them in the creation/evolution sequence. But this theme doesn’t come through as strongly as it could.

There are hints of that in Aronofsky’s film — not least in the fact that Adam and Eve shine with the light of their unfallen state, different from all the creatures that came before them in the creation/evolution sequence. But this theme doesn’t come through as strongly as it could.

Also, as Greg Thornbury has noted, the film misses out on the covenantal aspects of the Genesis story. It concludes with Noah passing on to his children a birthright that he received from his father Lamech — a birthright that immediately receives the divine imprimatur of the rainbow, and a rather supernatural rainbow at that — but the sense of God making a promise to his people is only hinted at, if that.

But then, there’s only so much a filmmaker can do when he has decided to present God indirectly, through visuals, rather than verbally, through dialogue.

(Incidentally, if Noah did everything on the basis of those two brief visions, then how did he know the exact measurements he should follow when building the Ark?)

I agree with those who feel that some of the characters were underwritten. I would have loved to spend more time with the Watchers, myself. And if Tubal-Cain was supposed to represent the “dominion” way of Genesis 1 — versus the “stewardship” way of Genesis 2 — then I think he could have been a bit more complex, too.

But on balance, I still like this film, a lot. And I’m happy to see that it did so well on this, its opening weekend. Here’s hoping that it leads to many fruitful conversations, and that it leads to even more Bible-themed films down the road.