“The Word became flesh,” according to John 1:14, but that flesh has been hidden, for the most part, in movie portrayals of Jesus. At certain key points in his life, history and even tradition would dictate that Jesus ought to be depicted nude — and there are good theological reasons for doing so. But most films have tended to shy away from nudity in their own portrayals of those parts of the Jesus story.

“The Word became flesh,” according to John 1:14, but that flesh has been hidden, for the most part, in movie portrayals of Jesus. At certain key points in his life, history and even tradition would dictate that Jesus ought to be depicted nude — and there are good theological reasons for doing so. But most films have tended to shy away from nudity in their own portrayals of those parts of the Jesus story.

There are some obvious reasons for this reticence, of course, starting with the fact that film, for much of its history, has been forced to skirt around images of nudity in general, and images of male nudity in particular. Plus, when a film does show someone’s nudity, it does not merely show us the character’s nudity; it shows us the actor’s nudity as well, and the knowledge that we are seeing an actor’s naked body can sometimes distract us from the character he is playing. This is especially true when the character is meant to be an embodiment of divinity like Jesus.

There have been at least three significant exceptions, though — three films that each depict the nudity of Jesus at a different key point in his story.

First, The Nativity Story (2006) shows Joseph holding the naked baby Jesus up in the air immediately after the child is born:

There is actually another shot before this one, which gives us an even clearer look at the baby’s naked backside, but I’d rather not post it here. I will note, though, that the nudity here underscores the fact that God, in Jesus, has become both human and vulnerable — and that this film makes a point of showing not only the baby himself but a bit of the muck that you typically get on a baby when it has just been born. (Someone who saw an unfinished rough cut of the film once told me that there was originally less muck on the baby, so some of it might have been added digitally.)

In this film, the baby is shown in all its messy nakedness for more or less the same reason the filmmakers made a point of casting actors of a certain ethnicity or showing the details of everyday life in a first-century village; it’s all part of a general effort to be “realistic”. But the “realism” of this scene only goes so far. While this film, like a few others, does show Mary experiencing labour pains, it does not show Joseph or anyone else cutting an umbilical cord; the baby seems to have come out of the womb untethered. Even more interestingly, there is a point during the delivery of Jesus when the film suddenly fades to white. Details like these, intentionally or not, seem to hark back to a tradition that is at least as old as the 2nd-century Infancy Gospel of James, which holds that “a great light appeared in the cave so that their eyes could not bear it. And a little while later the same light withdrew until an infant appeared.”

Be all that as it may, the main point here is that The Nativity Story does, in fact, show the baby Jesus naked, and it is the only film I can think of right now that does this. In other artforms, however, especially in the west, there is a long tradition of showing the infant naked — and of even drawing our attention to his genitalia — as a way of showing that God has become human. See, e.g., the detail here from Hans Baldung Grien’s Holy Family (1511). Leo Steinberg documented this pattern extensively in The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion, where he noted that “the sex of the newborn is a demonstrative sign” which verifies “the humanation of God”.

Be all that as it may, the main point here is that The Nativity Story does, in fact, show the baby Jesus naked, and it is the only film I can think of right now that does this. In other artforms, however, especially in the west, there is a long tradition of showing the infant naked — and of even drawing our attention to his genitalia — as a way of showing that God has become human. See, e.g., the detail here from Hans Baldung Grien’s Holy Family (1511). Leo Steinberg documented this pattern extensively in The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion, where he noted that “the sex of the newborn is a demonstrative sign” which verifies “the humanation of God”.

The Nativity Story doesn’t go so far as to draw our attention to the genitalia of the Christ child — they’re actually obscured throughout the scene, which limits our vision to his back and side — but, believe it or not, I can think of one film that does draw our attention to them, though it does so without nudity. Specifically, I am thinking of Franco Zeffirelli’s Jesus of Nazareth (1977), which is the only film I can think of that devotes a significant bit of screen time to the circumcision of Christ:

The circumcision of Jesus is mentioned briefly in Luke 2, and it has its own feast day on the Christian liturgical calendar, but it is virtually ignored in Jesus films — even The Nativity Story omits it — and on the rare occasion that a film does include it, as in Jesus (1979), it merits little more than a quick mention by the narrator.

Zeffirelli’s film, on the other hand, pays significant attention to the Jewish customs within which Jesus was born and raised; the man who is about to perform the circumcision even declares that “this is the seal in flesh of the covenant between the Lord and his people.” So even if the film does not show any flesh during this scene, it certainly encourages us to think about the flesh, and what it means.

As shown in this film, the moment of Jesus’ circumcision — the moment when the baby Jesus cries — is also what catches the attention of Simeon, the old man who was told by God that he would not die until he had seen the Messiah. In Luke’s gospel, Simeon speaks to Joseph and Mary on a separate occasion, when they go to perform the purification rites required 33 days after the circumcision, as per Leviticus 12. But Zeffirelli conflates the two episodes, so that Simeon hears the child cry and then approaches the table, where he directs our attention to the child once more:

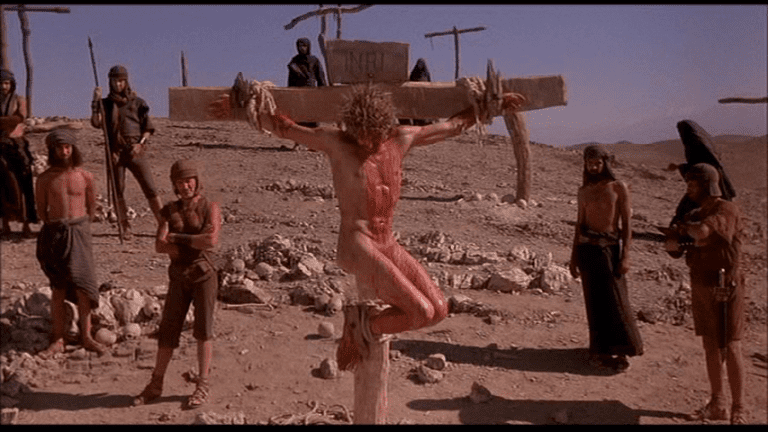

The second episode from Jesus’ life that warrants depicting him in the nude is the Crucifixion, and the one film I can think of that actually does this — as I mentioned in my recent post on depictions of the Cross — is The Last Temptation of Christ (1988):

This film features quite a bit of nudity, of course — some of it male, some of it female — so it is not surprising that it turns up here, too. Jesus appears nude in one earlier scene, as well, when the Roman soldiers beat him in prison. Scenes like these are remarkable because nearly every other depiction of Jesus in film lets him wear at least a loincloth at this point in his story. And yet, early Christian tradition tells us that Jesus was crucified naked. St. Cyril of Jerusalem — who may have witnessed crucifixion himself, since he was already in his 20s when the emperor Constantine abolished the practice — wrote in his Catechetical Lectures that early Christians, who were baptized in the nude, did so partly to identify with Christ in his death.

Director Martin Scorsese claims in an opening title card that The Last Temptation of Christ is based on a work of fiction, with no direct ties to the Jesus of history or the gospels, but he strove for historical accuracy in this one area, at least, and he based his depiction of the crucifixion of Jesus (but not the crucifixion of the thieves) on an illustration that was first published in the Israel Exploration Journal in 1970. Two years earlier, archaeologists had discovered the bones of a crucified man named Yehohanan, and osteologists were able to reconstruct Yehohanan’s position on the cross by studying his wounds — and as you can see, the artist who drew the accompanying picture assumed that Yehohanan was naked when he was crucified, too.

Director Martin Scorsese claims in an opening title card that The Last Temptation of Christ is based on a work of fiction, with no direct ties to the Jesus of history or the gospels, but he strove for historical accuracy in this one area, at least, and he based his depiction of the crucifixion of Jesus (but not the crucifixion of the thieves) on an illustration that was first published in the Israel Exploration Journal in 1970. Two years earlier, archaeologists had discovered the bones of a crucified man named Yehohanan, and osteologists were able to reconstruct Yehohanan’s position on the cross by studying his wounds — and as you can see, the artist who drew the accompanying picture assumed that Yehohanan was naked when he was crucified, too.

Finally, there is the Resurrection. Most of the films that do depict it in some way usually show Jesus wearing a robe, not unlike the robes he wore earlier in the film, or not unlike the glowing white robes that the angels might wear. But one striking exception to this is Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004).

In this film, the camera moves across the tomb before settling on a tight close-up of Jesus, who has apparently been resurrected in a sort of crouching position. We can see right away that his shoulders are bare. Then his eyes open, and he stands up, and we get a quick but clear glimpse of his naked thigh through the hole in his hand:

A split-second later, he begins to walk, and although our glimpse of the back of his thigh is blurred, we get the distinct, if brief, impression that Jesus might not be wearing anything at this point in the story — not even a loincloth:

Note: It would not matter for our purposes if the actor was actually wearing something on the set that day. What matters is the image — and it seems that Gibson, after following all the artistic conventions that show Jesus wearing a loincloth on the cross, decided to suggest that Jesus might not be so adorned in his life after death.

Again, there’s a theological reason for this. As Steinberg notes, artists like Michelangelo sometimes depicted the resurrected Jesus fully nude — a fact that later curators have sometimes tried to cover up, as you can see from the picture to the right — and the reason for this nudity is that the resurrected Jesus has restored humanity to the innocence that Adam and Eve once enjoyed before the Fall: “How then could he who restores human nature to sinlessness be shamed by the sexual factor in his humanity?”

Again, there’s a theological reason for this. As Steinberg notes, artists like Michelangelo sometimes depicted the resurrected Jesus fully nude — a fact that later curators have sometimes tried to cover up, as you can see from the picture to the right — and the reason for this nudity is that the resurrected Jesus has restored humanity to the innocence that Adam and Eve once enjoyed before the Fall: “How then could he who restores human nature to sinlessness be shamed by the sexual factor in his humanity?”

This link between the innocence of Adam and the nudity of the resurrected Christ is echoed in the baptismal practices of the early Church. As noted above, converts were baptized in the nude back then, and St. Cyril of Jerusalem says they did this in imitation of Christ’s death; but he also says that they were baptized nude in imitation of “the first-formed Adam, who was naked in the garden, and was not ashamed.” Similarly, St. John Chrysostom, in his Baptismal Instructions, told the early Christians that they were baptized naked to “remind you of your former nakedness, when you were in paradise and you were not ashamed.”

All this talk of baptism raises an interesting point that I hadn’t considered when I started writing this blog post. Early Christians were baptized in the nude, and you can find some very old depictions of the baptism of Jesus in which he, too, is nude — but I can’t think of any films that have depicted his baptism this way. Even in The Last Temptation of Christ, which imagines that John the Baptist was surrounded by naked and half-naked people chanting and swaying and cutting themselves, Jesus keeps his loincloth on when he kneels in the water and asks John to baptize him.

In any case, it is intriguing to think that Christian baptism once incorporated the key paradox of nudity: It can sometimes be used to shame people, as the Roman soldiers tried to shame their victims, but it can also be used to express a kind of purity for which no one needs to be ashamed of anything. And just as genitalia reflect the animal side of human nature, and are thus typically thought to be “lower” than the things which make us spiritual, the fact that God became man and redeemed humanity is expressed most potently in the fact that, yes, he now has genitals too.

The four films I’ve cited here are too discreet to depict the actual genitalia — which is only fitting, as that would draw our attention to the actors as much as it would to the character that they are playing. But in showing Jesus’ nudity the way they do, they encourage us to think about this aspect of the mystery that is the Incarnation.